Hugo Pictor amongst the Schutzgeister

Frederike Mayröcker draws, Milton Avery at home and in France, Anna Mendelssohn and Cody-Rose Clevidence, Carl-Heinz Wegert's micro-worlds

A trip last week to the Whitechapel Gallery ended up with Hugo Pictor in the bookshop introducing himself to a Frederike Mayröcker catalogue. The Vienna-based poet’s drawings were the subject of an exhibition at Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, in 2021.

The small works on paper had been a private art form for the poet, mostly shared with friends and family. Mayröcker had been resistant to exhibit them on their own, so the show added a table of her books, plus a sound installation of her Hörspiele (radio plays), and a screening of Traube (Grape), a 1971 television film, a collaboration with poet Ernst Jandl (Mayröcker’s partner) and Heinz von Cramer.

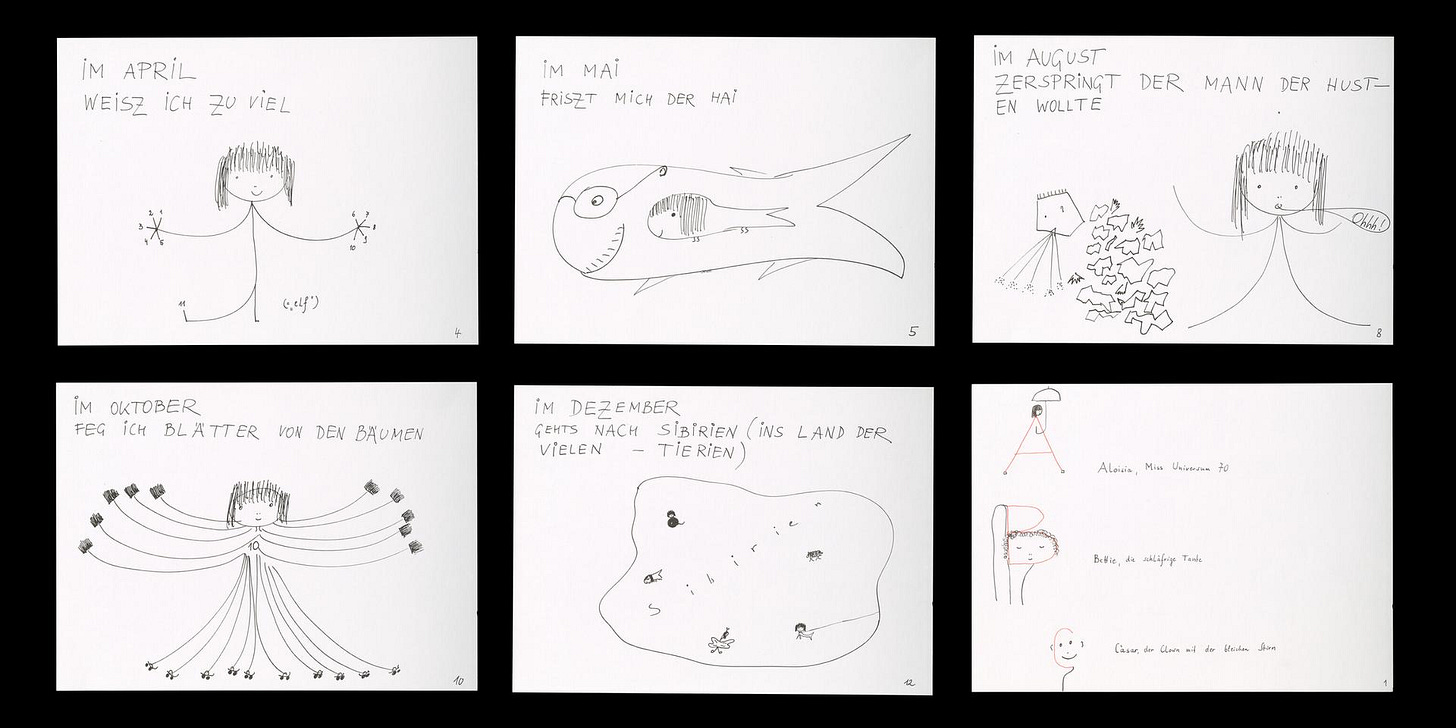

Published two years after the show, the publication offers documentation of the installation, reproductions of the drawings themselves, photos of the launch and opening - one of Mayröcker’s last readings before her death in 2023. The drawings include several sequences of the Schutzgeister (Guardian Spirits), pen drawings of a variety of angel figures accompanied by 1 or 2 Lines of German text.

‘In April I know where to go’ figured out Hugo Pictor on Google translate, whilst looking at the sheets above. Also: ‘In August the man who wanted to cough burst’, which was something Hugo Pictor could identify with. He had also spent many hours when he should be illuminating manuscripts reading English translations of Mayröcker’s wild, engaged poetry, many courtesy of Calcutta-based Seagull Books, variously translated by Katy Derbyshire, Donna Stonecipher, and Roslyn Theobald.

But how did Mayröcker’s drawings relate to her poems? The book reproduces two typescripts, undated and from 1983, where Mayröcker writes of ‘drawings or visual poems’ created on the ‘sidelines’ of her work; ‘harmless marginal notes, mostly done after or during more difficult main works, perhaps something in which I “rest” myself’. Works like those in this exhibition are ‘games that I play with myself when I am completely empty’ or in situations ‘too profound or too banal for words.’ She connects them to childishness, doodles, everyday ‘sorrows, feelings of loneliness’ and animals, particularly cats.

The original German typescripts are a mess of qualifying, editing, deleting, re-writing, which suggests a restless dissatisfaction with articulating what this practice involves. But Hugo Pictor also read them as a moving attempt to define a ‘private’ area of her creative work, a space that valued naivety, lack of facility, a privileged insignificance.

Hugo Pictor was off to the book pile for his copy of Mayröcker’s Requiem for Ernst Jandl (translated by Theobald) to try and fathom what it was that the drawings were marginalia for, and what might have led to Mayröcker’s feeling of post-poem making emptiness. Hugo Pictor opened the book at random:

Obrist’s written contribution for the catalogue is a memoir detailing how he met Mayröcker through his friendship with artist Maria Lassnig. He outlines Mayrocker’s method of creating poems: writing all day and night, in the kitchen, in bed when she had just woken up, everywhere, the creative act dependent on the whole apartment and her movements within it:

Books, papers, and baskets filled with cards were stacked everywhere in the apartment. On these cards, she noted what seemed important to her - remarks from acquaintances who spoke with her, a sentence overheard in the park, stories from strangers sitting next to her at a café. When she worked on a book, she would take card after card from the baskets and weave them into her prose, which tells a story without narration. Thinking of the connections of home and art making, Hugo Pictor tripped over his encyclopaedia draft excluder, then emerged from the book pile feet first holding Milton Avery: Home and Studio, a two volume ‘special edition’ published by Victoria Miro alongside its 2017 exhibition of the artist. For Hugo Pictor, remembering a rare trip to Mayfair to see it, it had also been a prelude to the fine 2022 Royal Academy show .

Within its ingenious, pale blue cardboard container were two paperback books. One contained a photographic series by Gautier Deblonde of Avery’s family home and studio, in Manhattan. It showed the open views through Avery’s apartment, the many paintings on the wall, the desks and bookshelves, boxes of pastels, the high-storey Manhattan window views of the building across the street. It was hard not to find comparisons with the distinct forms, colour fields, and atmosphere of his paintings.

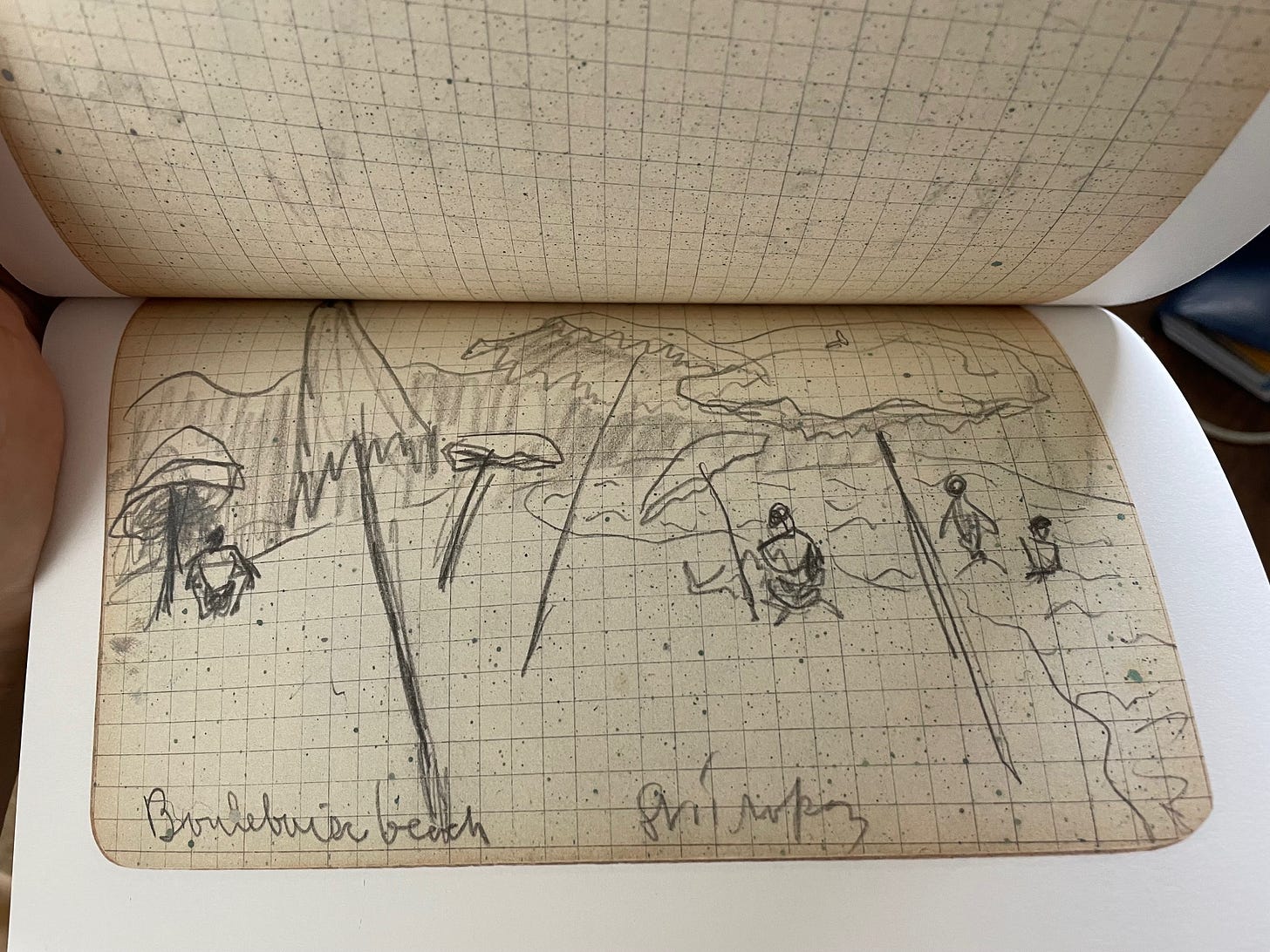

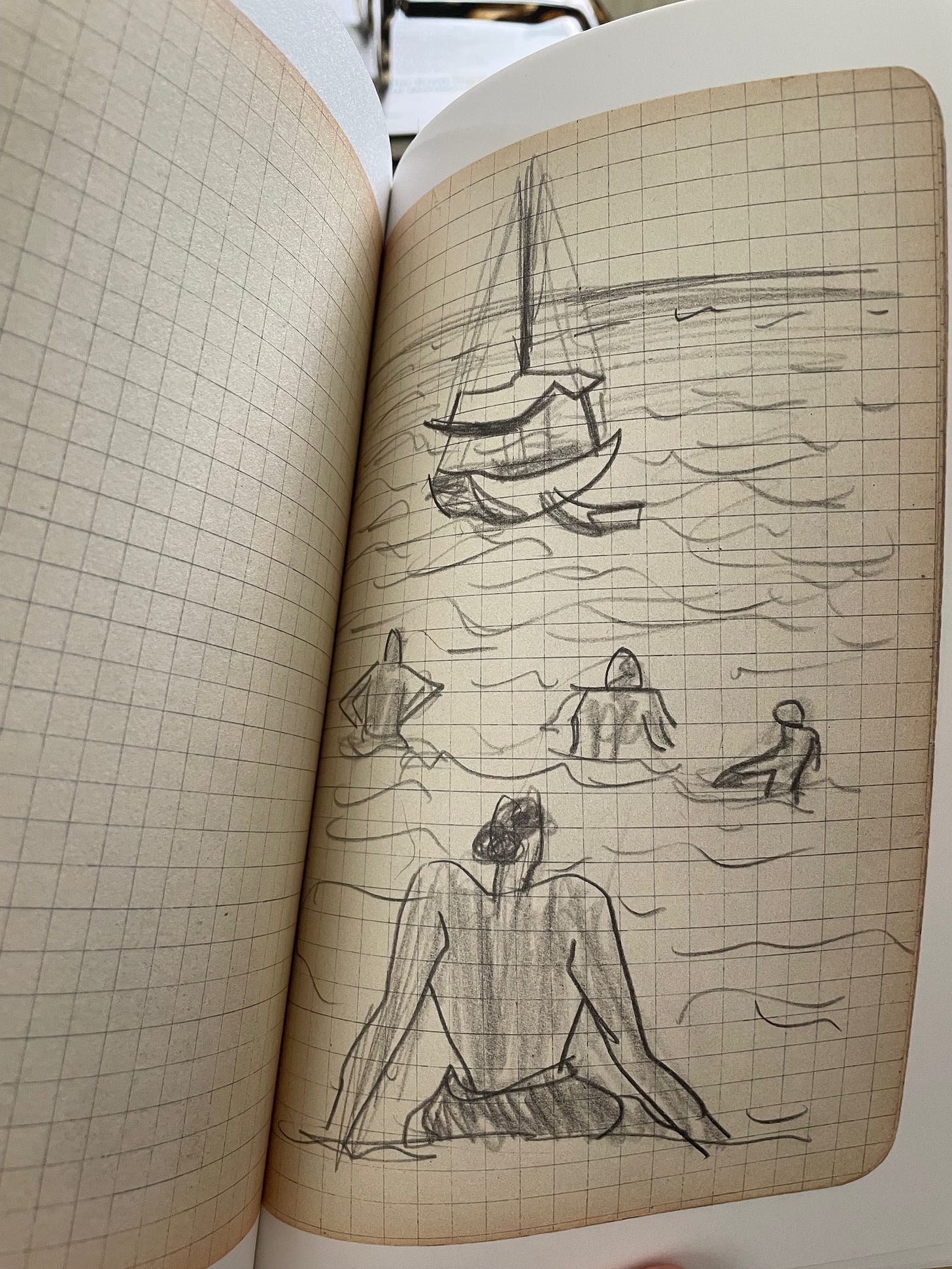

The second book offers another take on this subject: a sketchbook from Avery’s first and only trip to Europe, over 200 pages of sketches from the South of France in 1952. Now the repetitive sketchiness was what struck Hugo Pictor, the restless return squared page after page, to beach, sea, boat, tree; the quick grasping of compositions and geometries, a written mnemonic of rudimentary colour notes.

The Royal Academy catalogue had no paintings specifically identified as from this trip, but there was a beach scene from a few years before, and Hugo Pictor juxtaposed it with the later sketches to try and intuit some sense of the ongoing movements from pencil to paint to pencil, from beach to canvas (and apartment) in Avery’s life:

When thinking about mid-century New York painters, Hugo Pictor liked to balance himself by holding James Schuyler’s Selected Art Writings (Black Sparrow Press, 1998) in one hand, and John Ashbery’s Reported Sightings: Art Chronicles 1957-1987 (Knopf, 1989) in the other. But neither poet includes a review of an Avery show.

Like Hugo Pictor’s own Manhattan years, it was hard not to wonder if Avery’s life and paintings had not breached some conditions of style and sociality that connected Ashbery and Schuyler so strongly to, say, Fairfield Porter and Jane Freilicher. It was good not to get paranoid about such things, Hugo Pictor shouted into the cloister. He imagined Scuyler and Ashbery frowning in 1982, as they opened Time magazine and read Robert Hughes review of Avery’s Whitney Museum show:

His figures are really ideograms, and they tell us as little about bodies as his small gray painting of a diving sea bird tells us about gulls. Its interest is focussed wholly within the colour - that rich “gray,” actually a complicated melding of green, gray and dark rose, which pulsates with such airy serenity around the white patch of a bird. In the same way, the human figure in Avery is a locus of colour, something to carry a desired area of pink or blue. Just like Avery’s apartment, thought Hugo Pictor, in Deblonde’s photos of it, and in that almost unbearable posthumous tidiness. Hugo Pictor turned out the light, turned it back on, turned it off, and thought of all the beautiful apartments he had lived in.

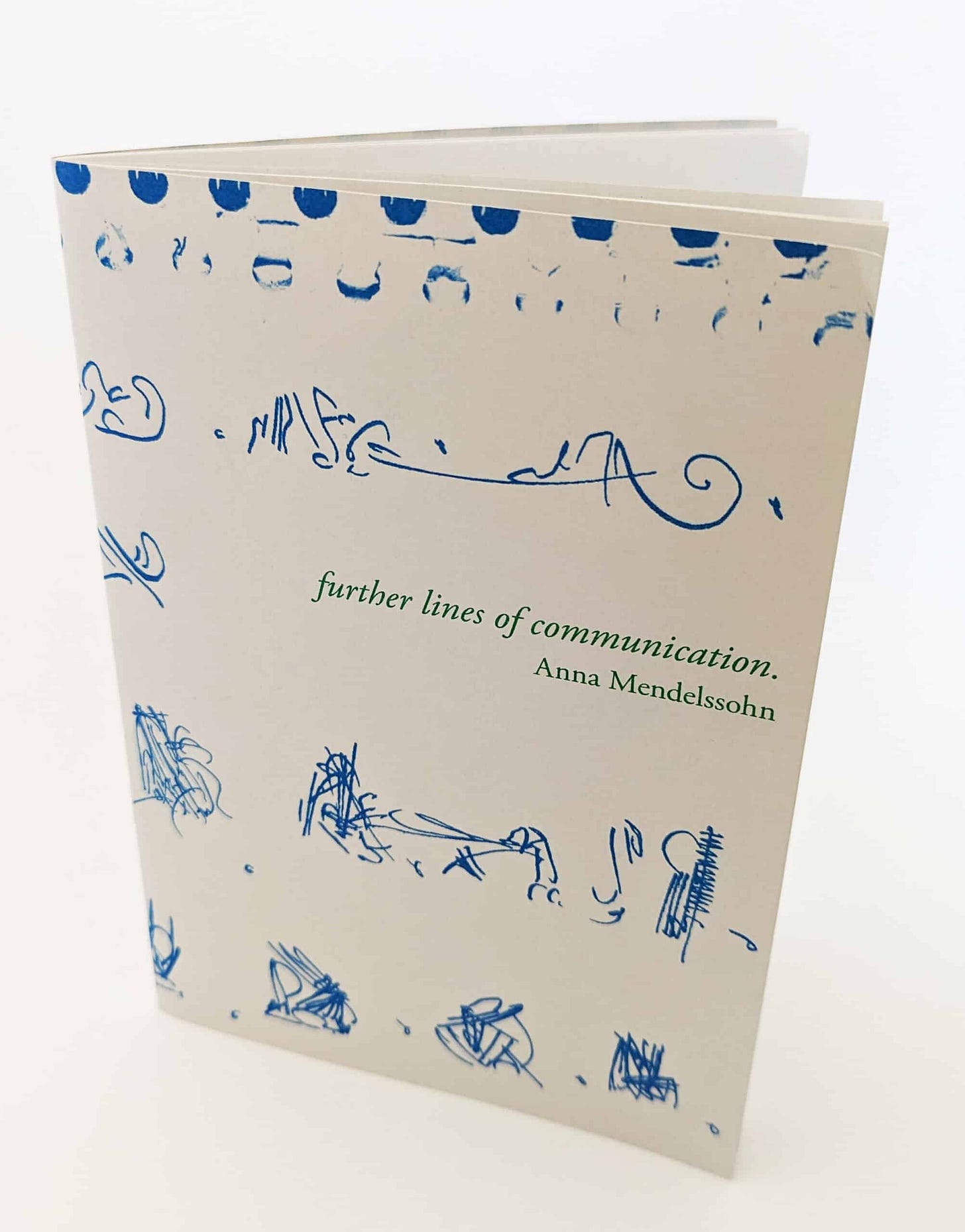

The reason Hugo Pictor went to the Whitechapel Gallery was to see Anna Mendelssohn: Speak, Poetess, a display of poems and works on paper from the recently catalogued archive at the University of Sussex. An essay (available as a handout in the gallery) by curator Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung offered an introduction to show and artist, whilst there is a useful online sample of I’m Working Here: Collected Poems, edited by Sara Crangle.

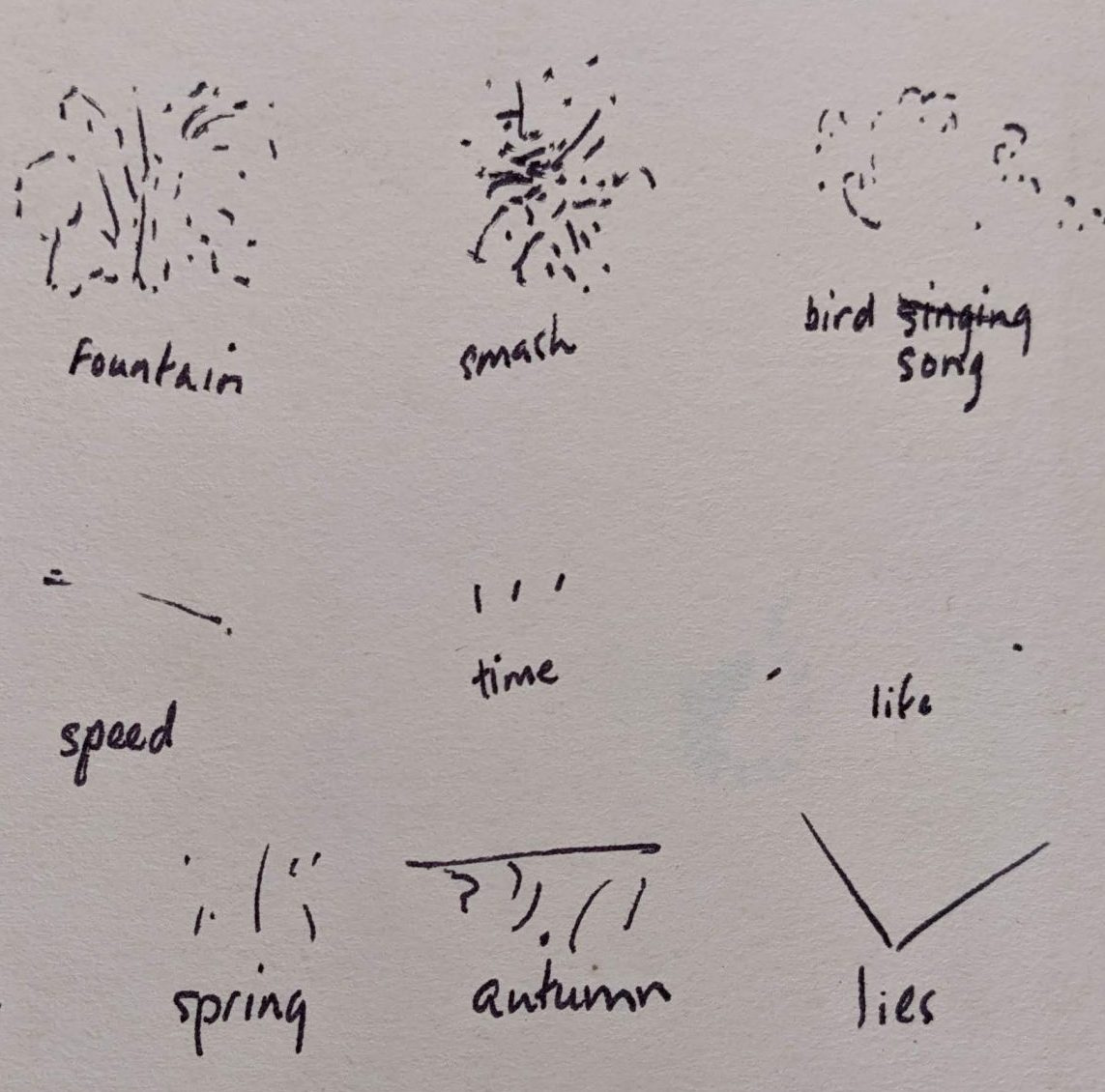

Hugo Pictor was pleased to find a small pamphlet of Mendellssohn’s poems had been produced for the show, whose cover reproduced some of the ideogram, glyph and scrawl works found in the show.

Harder to grasp in vitrines were Mendelssohn’s dense ink drawings, such as Untitled (“aphrodite”)(c. 1990 –1993). Like other visitors, Hugo Pictor got pulled into photographing everything on his phone, but the jpegs were stubbornly unrevealing. Some works were part of larger sketchbooks, of which only a single spread could be displayed. It is to be hoped, as Hugo Pictor often declaimed of some new enthusiasm, that a monograph is forthcoming, or a trip to the archives in Brighton.

For now, Hugo Pictor agreed with Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung’s sighting in the drawings of ‘Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s allegorical paintings, whirring with the drama and dynamism of Cubo-Futurism, and… the free association of images and text honed by the Surrealists’. HP also nodded keenly whilst reading Joe Luna’s article on Mendelssohn’s relations to traditions of traditional Jewish lamentation, finding his own parallel in the travelling book-pile he turned to on the train home to Hastings.

This contained diptych chapbook DEARTH & GOD’S GREEN MIRTH by Cody-Rose Clevidence. Its sequences of poems shared with Mendelssohn an ongoing, urgency, sprawl, texture, and engagement, plus extra 2024 Chthulucene emergency: “and I, violet with meaning-making, rife with words, all-searching -/ all sensing eye of oviod doubt, closing, closing - the fishbowl sky following my gaze-”

Finally, when Hugo Pictor returned to the Scriptorium, trying to process these many readings and travelings, he summoned up the poetry-art collaborations of the Munich based artist Carl-Heinz Wegert (1926-2007), whose works he had first encountered in the current Gesture and Line: Four Post-war German and Austrian artists exhibition at the British Museum.

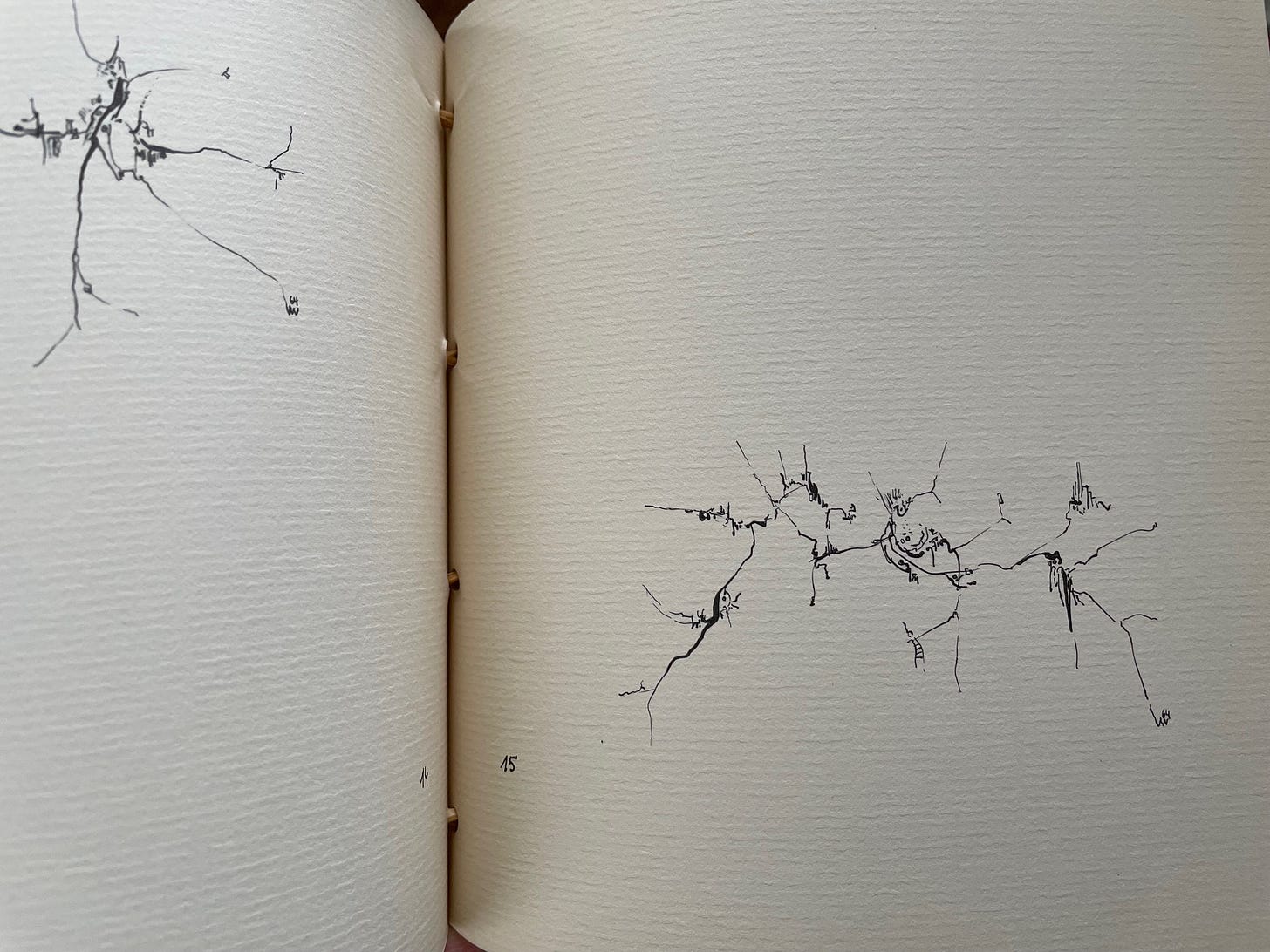

One of the highlights of that show was the tiny spiral notebook from 1973 with green covers (105 x 75mm), on each page of which Wegert made a tiny signed and dated drawing, often on walks around Munich. A similar style of drawing appeared in various publications of 1960s and 70s, and Hugo Pictor was spending much time lately wondering what exactly these drawings were, how they might function as notation, seismographs, description, and diagram, all of which their tiny forms suggested.

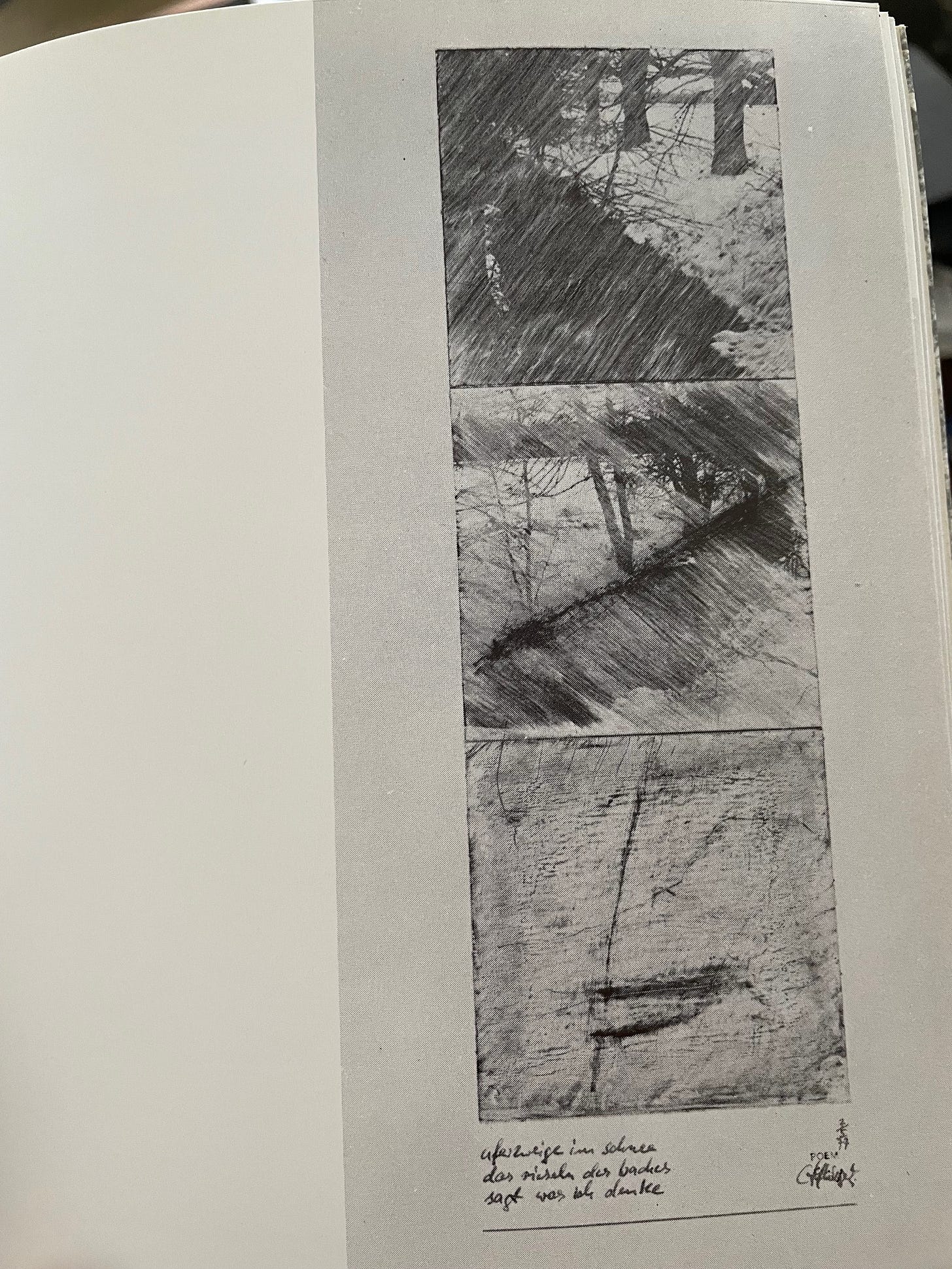

Below, for example, are a couple of spreads from a chapbook of George Heym’s ‘…in einem Schnee-Meer der Wolkenwalfisch’ published by Graphikum, Munich in 1964, where Wegert seems also to have handwritten the text, setting up correspondences between writing, copying and the drawings that are interspersed throughout:

Later, in a 1974 collaboration with the poet Adolf George Bartels, the poems are typeset, generally of only two to five short lines, so the drawings function alongside like additional small stanzas. In another project, Wegert’s own often haiku-inspired poems are written alongside printed images, or incorporated directly into the body of paintings on canvas. In one example from the book POEM-ART (1977):

The poem in this one reads:

uferzweige im schnee

das rieseln des baches

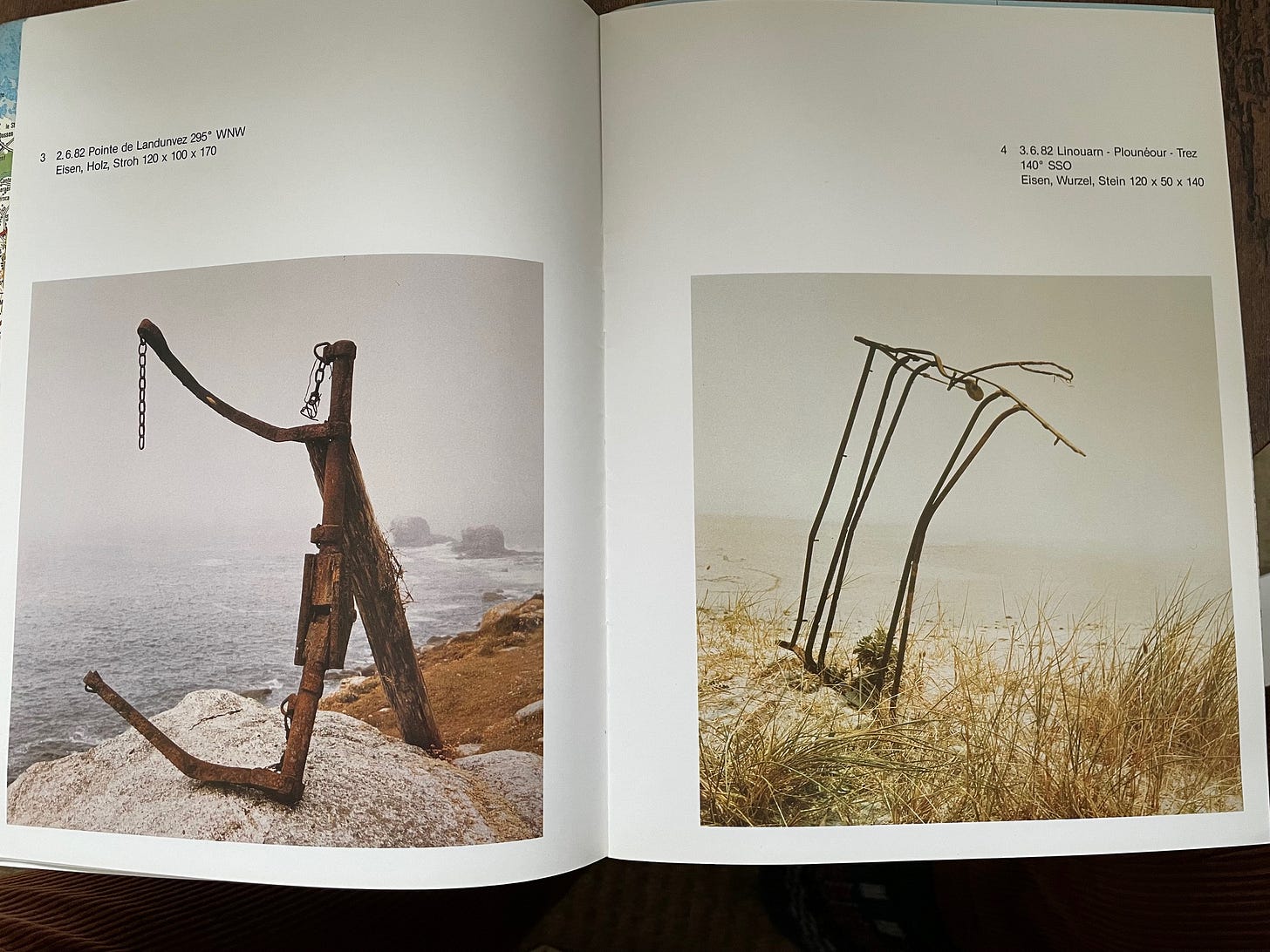

sagt was ich denkeWhich once again sent Hugo Pictor to google translate, which came up with ‘bank branches in the snow/ the trickling of the stream/ says what I think.’ It was a very different poetics to Mayröcker, but connection was felt more in the image, where the aesthetics of the earlier notebooks expanded in affinity with the lines and patterns of the environment, amongst the layering of different media. In Amorika Findlinge (1982), a record of a journey the artist made across Brittany, similar shapes and structures appear in the objects Wegert found, composed, abandoned on his way:

Such objects reappear in a memorial video of Wegert’s studio (and a series of photographs) which makes an obvious link back to Avery. The two studios seem somewhat similar, although Wegert’s wasn’t also his non-work home. A tentative connection, too, of Wegert with Mendelssohn, whose ink drawings and ideograms also seem to seek an attuned discovery on paper of mind, body, place, and language.

What, though, of the play, rest, childishness and animals that Mayröcker found in her ‘marginal’ drawings? Hugo Pictor went back to Room 90 at the British Museum, looked again at Wegert’s micro-worlds in their tiny notebook. If he became small enough to inhabit those teeming, inked universes, Hugo Pictor would surely…. what?