Self-Publishing: The Utrecht Psalter Method

The Self-Publishing academic triumph of Dimitri Tselos, Remembrances and Confessions by Emma Aars, Ulises Carrion becomes Paul Auster, Book X

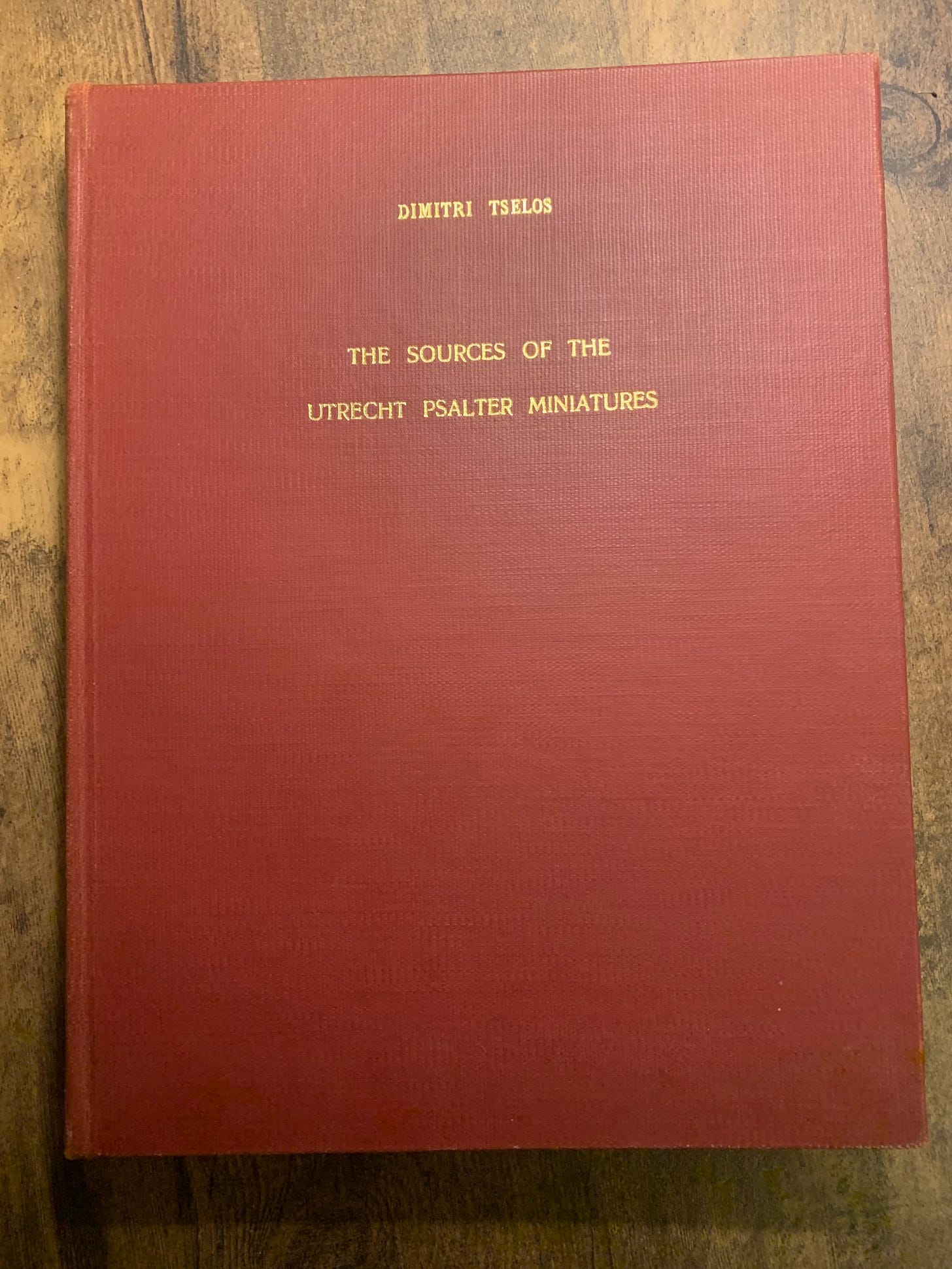

Hugo Pictor felt he had been neglecting the medieval lately, so his eye turned to the red and gold covers of The Sources of the Utrecht Psalter Miniatures by Dimitri Tselos. Hugo Pictor declared this book the most successful example of academic self-publishing EVER. Go read any essay that mentions this particular ninth-century illuminated psalter and there will invariably be a footnote on Tselos, this volume, as its title page has it, ‘Printed and Published/ Privately/ Minneapolis/ Minnesota/ 1960.’

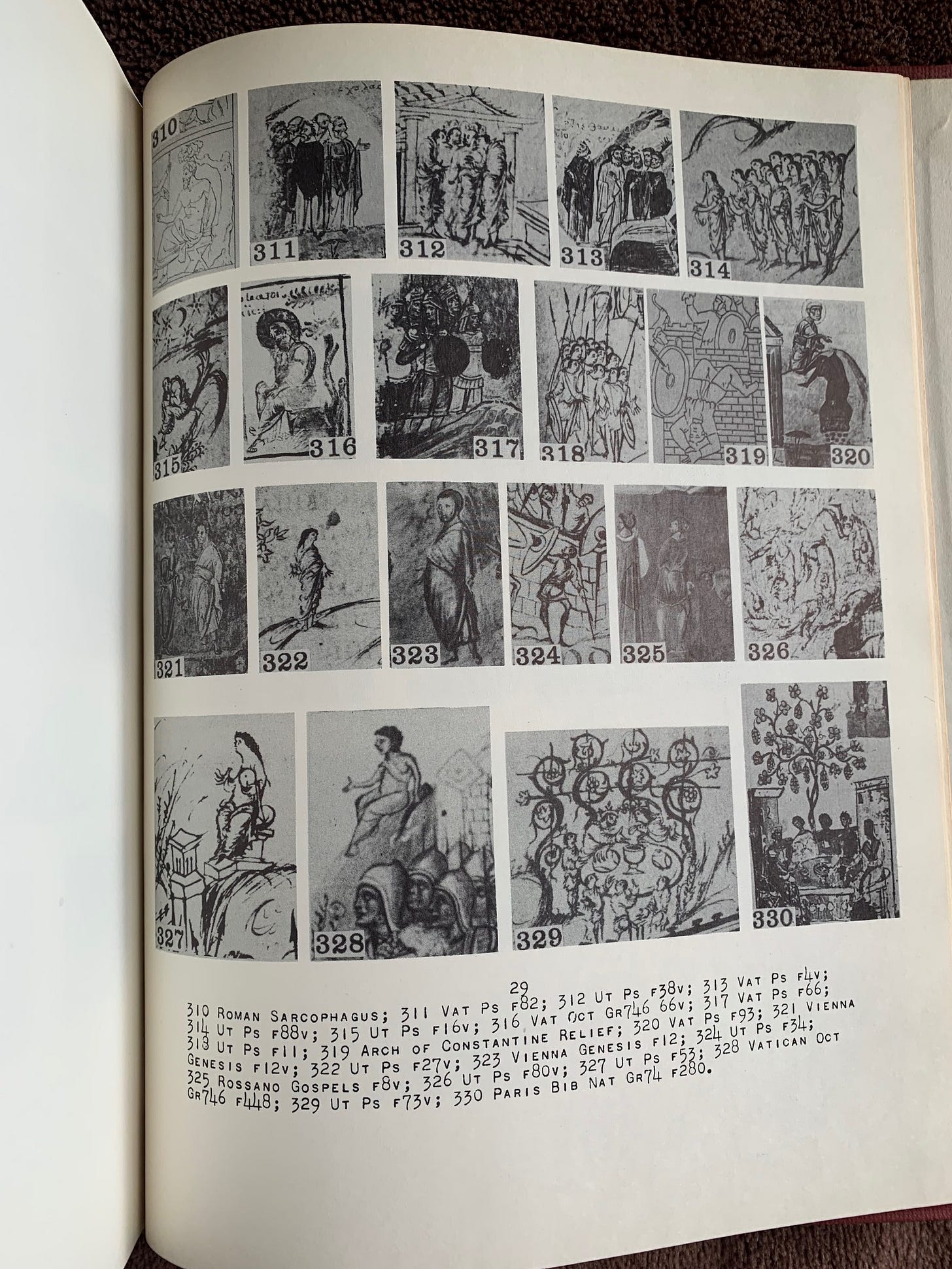

When Hugo Pictor did a V&A Academy Medieval Art course last year, to refresh himself about himself, there was Tselos again on the bibliography. Copies are at the non-existent end of scarce on the secondhand book market. If you do find one treat with caution the bookseller’s happy description that there are 361 illustrations, something that, like booksellers themselves, is technically if scurrilously true.

As Hugo Pictor pieced together the story it went like this: In 1931, Tselos and Gertrude Benson published twin articles in Art Bulletin under the general title “New Light on the Origins of the Utrecht Psalter”. Both focussed on likely sources of the Psalter’s remarkable illustrations. Benson identified early Latin ancestry for the miniatures with later connections to manuscripts at Reims, which suggested a no longer existent model from which illustrations of The Utrecht Psalter were copied.

Tselos wrote an article with the subtitle ‘The Greek Element in the Utrecht Psalter’. This model ‘was largely dependent for its typological scenes and pictorial motifs to the Greek tradition.’ It was this view of the Psalter which later formed the author’s PhD dissertation, extending the focus to look at the Psalter’s influence on Carolingian and later art. Which takes us to 1960 when Tselos embarks on his supremely successful act of self-publishing:

Publication of the results in the conventional manner has been considered but given up because of the large number of photographs which would increase the cost for a small edition to prohibitive levels… In the belief that there is a sufficient amount of new information on the stylistic and iconographic origins of the Utrecht miniatures to justify publication in some form, the study is presented in this abbreviated and orthodox form to those few institutions where the study of the subject is of more than casual interest. Hugo Pictor imagined Tselos collecting the bound editions from the University of Minnesota print shop (he was Professor of Art) then mailing them off to select Medievalists worldwide. Dear Ernst Kitzinger, he imagined him writing, it's finally finished! Hugo Pictor was preoccupied with the vanished Book X that Tselos claimed as model for the psalter’s illustrations, a missing link between 3rd and 10th century.

It was startling how much of Book X could be extrapolated from what came before and after. Hugo Pictor also wondered if X was actually somewhere in the chaos of his own scriptorium, and felt guilty for all the centuries of speculation he had caused.

After its publication (the edition I have indicates a second printing) Tselos felt that his work on the Psalter was done. His book was in libraries, to be cited and inter-library loaned whenever The Utrecht Psalter was under discussion. Tselos wrote of his Medieval “retirement” ‘in order to concentrate on some problems in modern art which I had been cultivating collaterally for the past thirty years’. An article on Frank Lloyd Wright needed finishing, and (on two Fulbright scholarships to Greece, the country of his birth) Tselos based himself at the National Technical University of Athens to study the art of that country since the Greek War of Independence and the evolution of art in Modern Greece.

But The Utrecht Psalter would not leave Tselos alone. By 1967 this retirement was throroughly ‘disturbed’ by J.H.A. Engelbregt, a Dutch scholar who saw most American scholarship on the Psalter, Tselos included, as producing nothing but an ‘oncoming blinding light’. Tselos, struggling to remain polite, detailed Engelbregt’s biography in a footnote, noting that given ‘the enormous self-assurance…. the reader might like to know who he is’. In the main text of his ‘Defensive Addenda’ Tselos writes:

I decided to take this opportunity to reveal some new evidence that will, I hope, silence any future attempts at proving that its miniatures were original creations of the ninth century. Hugo Pictor had his own Utrecht Psalter hunch, which would have enraged Tselos. Despite his attraction to Book X and the pursuit of iconographic origins, Pictor couldn't stop himself seeing sources for its illustrations in the bird that just landed on the roof across the street, in the woman with a can of paint climbing a ladder, the tendrils of a spider plant that just got caught up in his hair, in the face that looked back at him in the bathroom mirror after he’d put Dimitri Tselos on the shelf and was cleaning his teeth. But Tselos won all the arguments because of self-publishing.

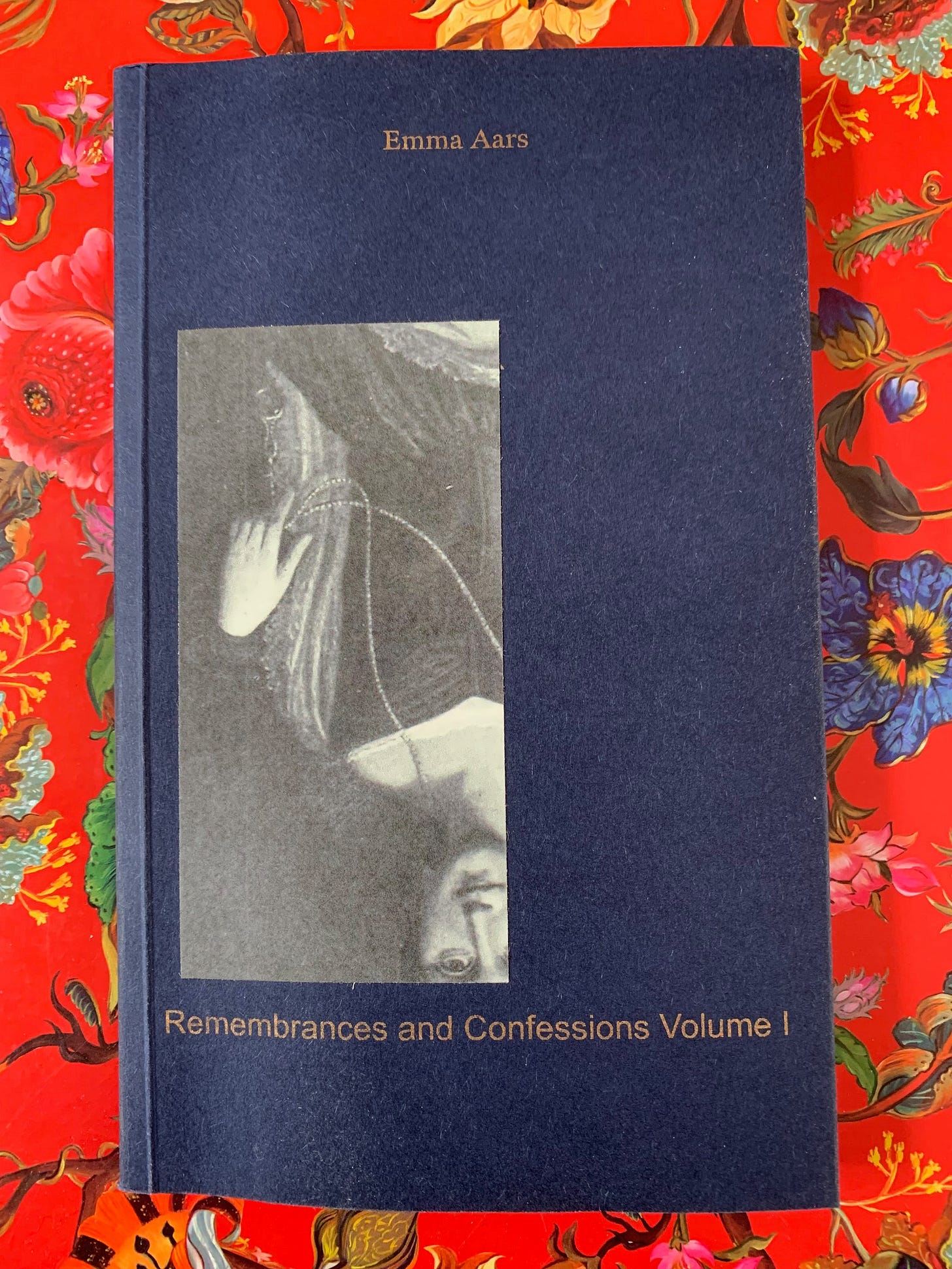

Emma Aars, says the back flap of this self-published volume, ‘is a Norwegian writer and artist based between Glasgow and Oslo.’ Her Remembrances and Confessions Volume 1 records her attempts to translate the nineteenth century writer Camilla Collett, a prominent Norwegian author of a novel that influenced Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, who is also Aars’ great-great-great-great grandmother. It is also, she adds, a project for the MLitt in Art Writing at Glasgow School of Art, so part of her own ‘becoming a writer’. What writing and translation might, do and could mean and involve is part of this splendidly designed book’s attraction and achievement.

As an early attempt to define what is underway the author writes: ‘this project, where I translate her [Collett’s] book as a method of getting to know the woman existing on these pages, embodying her absent presence.’ Indeed, the early sections of R&C has numerous restless elucidations of its own method. Take this:

To translate the experience of spending time with her books would take a lot more than dictionaries, and the literal translation faded into the background. At least it morphed into something else. I found myself reading her words, replacing them with my own, bringing the material, ephemeral, and autobiographical parts of the project to the centre, exploring what an expanded approach to translation would provide to the work.And, a few lines later, this develops and is re-phrased:

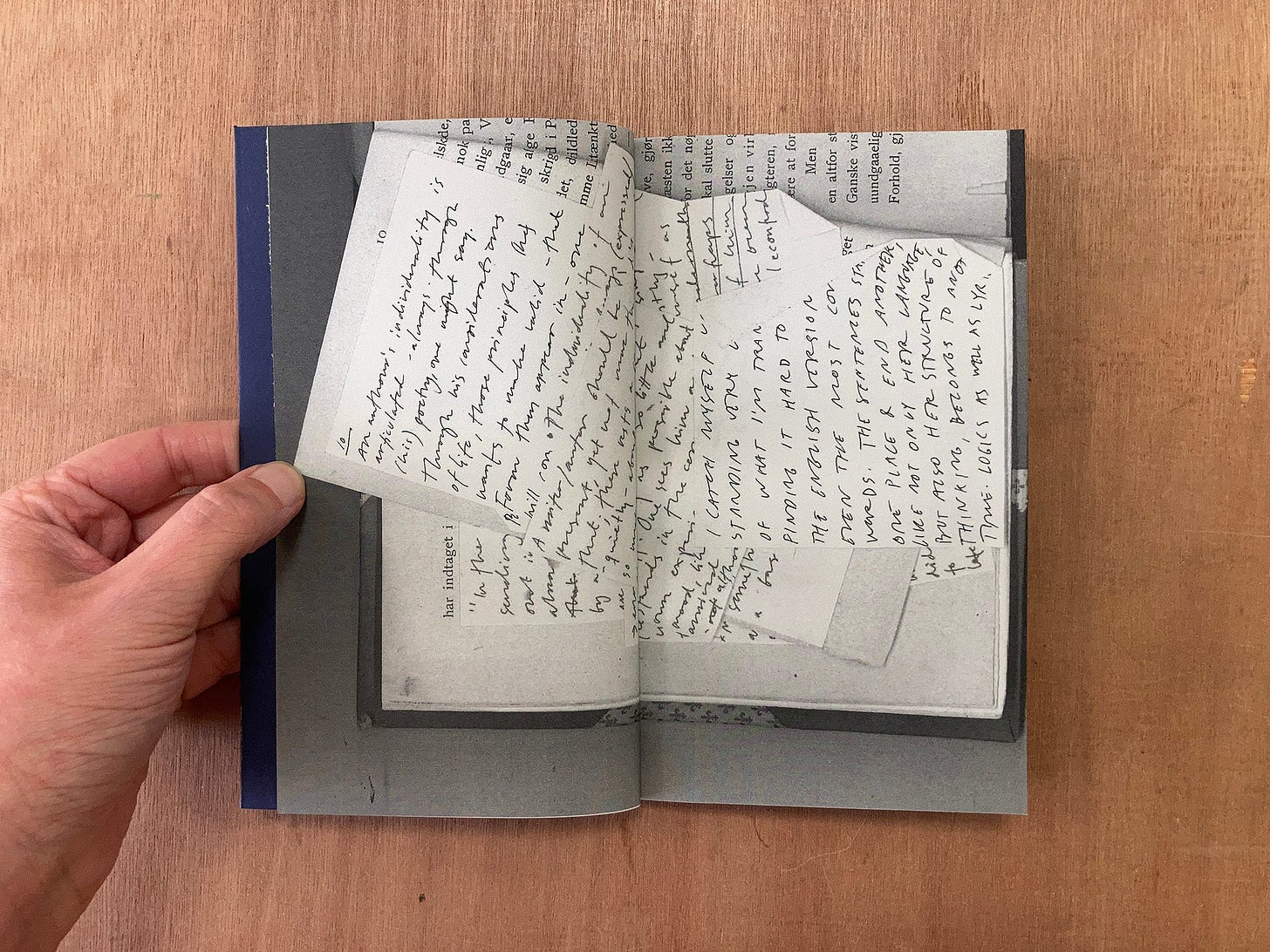

… where I explore how much my experience of spending time with Camilla’s works can be translated into other forms. By using different approaches beyond the literal, like various formats, genres, and materialities. I aim to capture what exists outside language, holding something beyond the words themselves that can’t necessarily be put into words, and otherwise would get lost in translation. By doing so, I give a language to things outside of language that are nevertheless part of Camilla’s works and life, existing between the pages of her book. As part of this, Remembrances and Confessions includes scans of collages that were part of an ‘archival box as artist book’ (more of this work can be seen here). The ‘main’ text also gets interspersed with meditations that involve looking through a window, sometimes into what might be Collett’s house. Aars is adept at unfolding this image of the window for seeing-thinking, aware that often her own watching face is unavoidably superimposed on the glass. She observes her ancestor’s moving about at home and suggests how those rhythms inform her writing:

Never-ending lines of moving from one room to the other like shifting between the scenes of a play or flipping the pages of a book. Bedroom, living room, kitchen, bedroom, boredom, bathroom, hallway. Short sentences become impossible in a life circulating this way. You wonder if her movements through the house became a tacit embodiment, impossible to put into words. Instead they exist as stretched monologues, endlessly seeking a [punktum]. I can’t describe all the ways this unfolds, thought Hugo Pictor, because I’m still reading and fathoming. Two details had struck him so far: firstly, the different aspects of the author’s research seek what Hannah Arendt says of Walter Benjamin’s collection of quotes: ‘crystallising decaying objects into new forms, rich and strange, like finding pearls and corals at the bottom of the sea.’ Later, after quoting this, Aars focusses on Arendt’s own ‘biography as autobiography’ of German writer Rahel Varnhagen (1771-1833), whose letters Collett finds in the University library.

There is a moment here when all the elements and layers of this project are at work: Collett reading Varnhagen, Arendt reading Varnhagen, Aars reading all three, and Benjamin too, as cited by Arendt. As well as this writing and reading the biographies connect: Vernhagen’s letters in their cryptic, almost unreadable handwriting almost lost after her death, whilst Arendt frantically mails off her quickly typed typo-ridden Vernhagen manuscript whilst fleeing to America. Aars coming centuries and decades later into this constellation of languages, manuscripts, relationships, cities, books, finding a way to be amongst, allow and add to all this turmoil and uncertainty:

Writing alongside Camilla, I think about how Hannah’s use of inconsistent quotations make her words fade into Rahel’s. This can be seen as a rejection of the biographical genre as an account of truth, or as an honest gesture towards the material she dealt with, immersed in the other person’s life to the point where they became inseparable. Resisting a transparent biography could also have been a way of embodying Rahel, as a gestural extension of her. Arendt saw Varnhagen as her ‘closest friend, though she ha[d] been dead for some hundred years’. Was that the aim, thought Hugo Pictor, the Mycelium way of going about things?

Secondly, amidst all the words and thoughts there was the book itself, the material book, her copy of Collett. ‘The book is small ,the two size of two palms, with yellowed paper that smells like dust. The gray woven fabric along the edge and corners of the cover, golden letters, a flower, and a field of fleur-de-lis.’ And so on, now with an added addition of her own annotated post-it notes ‘in a slim, black Pilot 0.4 pen’.

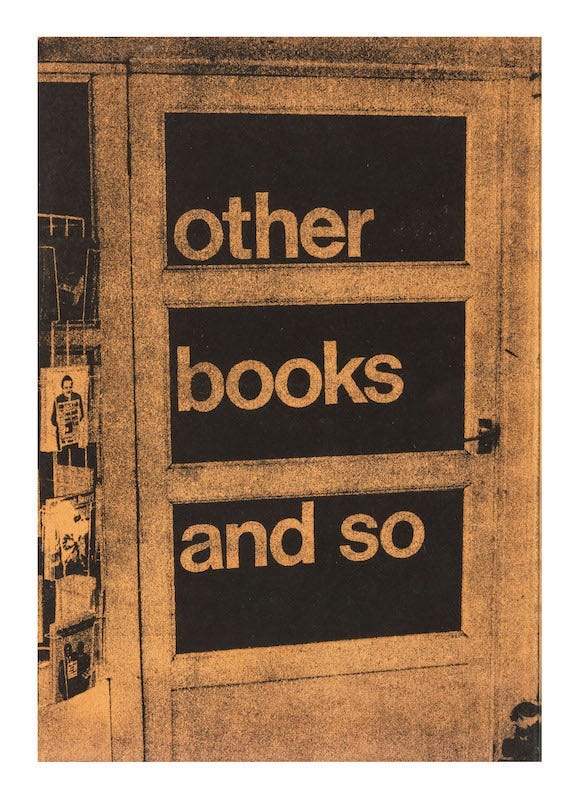

Finally, although he could scarcely remember it, rarely saw it, and had never personally come close to achieving it, an article by book artist and scholar Johanna Drucker had highlighted for Hugo Pictor the particular scholarship of the bookseller’s catalogue. It was definitely an art form in itself, he had to admit with his ex-bookseller snarl. Discussing a recent catalogue by New York bookseller Jonathan A. Hill of Ulises Carrión, Drucker remarks:

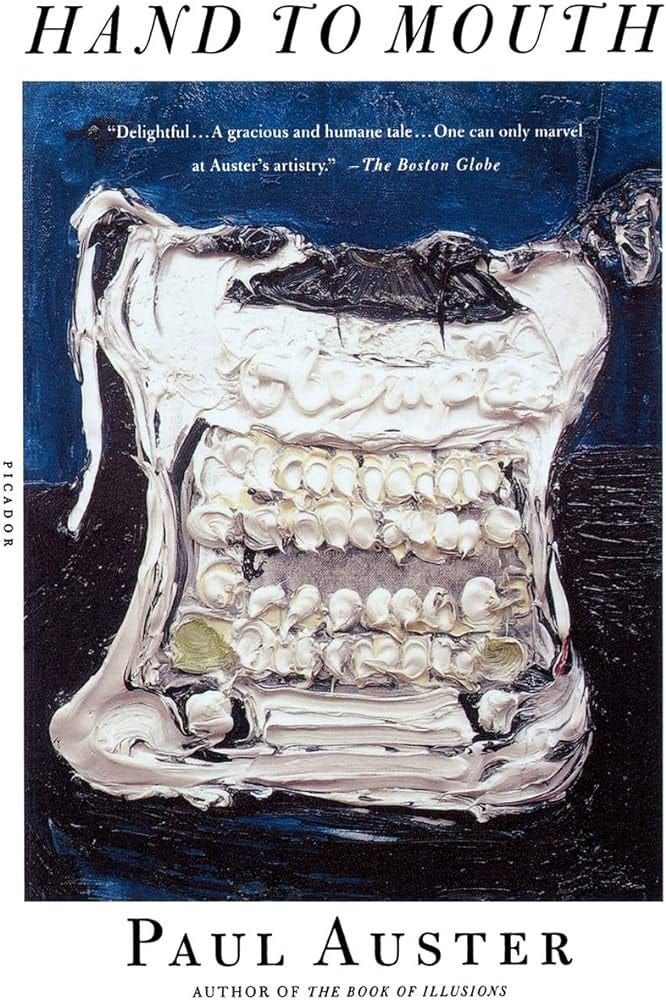

The catalogue is an exquisitely produced collection of facsimiles of the materials the bookseller is managing. The care with which the presentation has been put together and the production values in design, printing, photography, and expertly meticulous cataloguing make it an exemplary piece for study. As noted, a sale catalogue presents individual items, rather than embedding the objects within a narrative. In this regard it is radically different from an exhibition catalogue where the critical discussion frames the works.Maybe it was because he was always embedding objects in a narrative that Hugo Pictor’s secondhand bookselling career had ended so painfully. He also felt a need to counter here with an example from Paul Auster’s Hand to Mouth: A Chronicle of Early Failure, describing the young-ish Auster’s ‘comfortable’ job writing catalogue entries on 5X7 inch index cards for a Manhattan art book dealer.

One day Auster looks at the catalogue Marcel Duchamp designed for the 1947 Surrealist exhibition in Paris, its cover a spongy breast with the instruction “Prière de Toucher” (Please Touch). Now it is swathed in bubble wrap and brown paper and slipped into a plastic bag. ‘The joke has been turned into a deadly serious transaction,’ thinks Auster, ‘and once again money has the last word.’

Auster can see his boss loves the objects. He takes a certain pride himself in the catalogues they produce. But he can’t stay working in this ‘small shrine to the avant-garde’ and has a consuming sense of personal failure to be working there in his early thirties (Hugo Pictor snorted hysterically at that). Auster resigns, and later writes:

Apparently, a life of the mind was not incompatible with the pursuit of money. I understood myself well enough to know that such a thing wasn’t possible for me, but I saw now that it was possible for others. Some people didn’t have to choose. They didn’t have to divide the world into two separate camps. They could actually live in both places at the same time. Where were the books in Hill’s catalogue now? Hugo Pictor wondered, a little aggressively. He had wanted this week to stop always writing about new books, to travel in different layers of the subterranean paper pulp of codex history. Now he was ready for the new again, the fresh smell of its paper, its ideas and graphic design, the refusal to believe its sorry fate was to end up overpriced and scarce in the future’s antiquarian book catalogue. Though Hill’s Carrión was indeed a lovely piece of work, he had to admit, working through the PDF. Let it go, Hugo.

Then Hugo Pictor went off into Hastings Old Town and discovered that someone was neatly disposing of unwanted printed matter (see photo above). Hugo Pictor was a shy snapper and wished afterwards that he’d got closer, taken a side-on shot of all the spines. 501 French Verbs it was, and two volumes of Poldark. But there on the right? Book X? This was hours later, scrolling through photos on his phone. Hugo Pictor hurried back down the hill to the bin but found everything had disappeared.