Situationist Rubens: A Bananarama Grimoire

Gabriel Pomerand's Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire, The Situationist Peter Paul Rubens, the Paul Zweig Artaud retrieved, BananaramaArtWriting

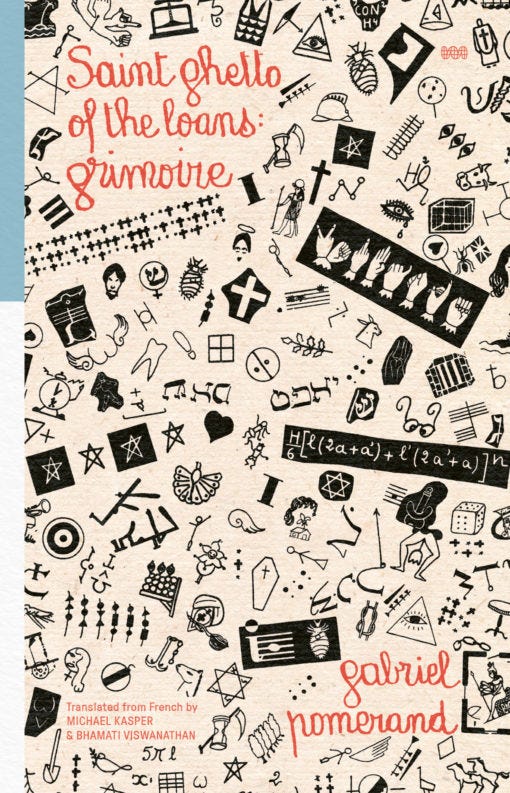

Given the unlikely reappearance anytime soon of his own 12th century illuminated manuscript marginalia epic, Hugo Pictor was happy to celebrate Gabriel Pomerand’s Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire, in an English translation by Michael Kasper and Bhamati Viswanathan, published by the enterprising World Poetry Books. Bilingual, of course, would usually mean French and English texts separated by the page gutter. Here both get confined to verso, with Pomerand’s ‘metagraphics’ filling the other page with a proposal that literary production shift into a different code altogether.

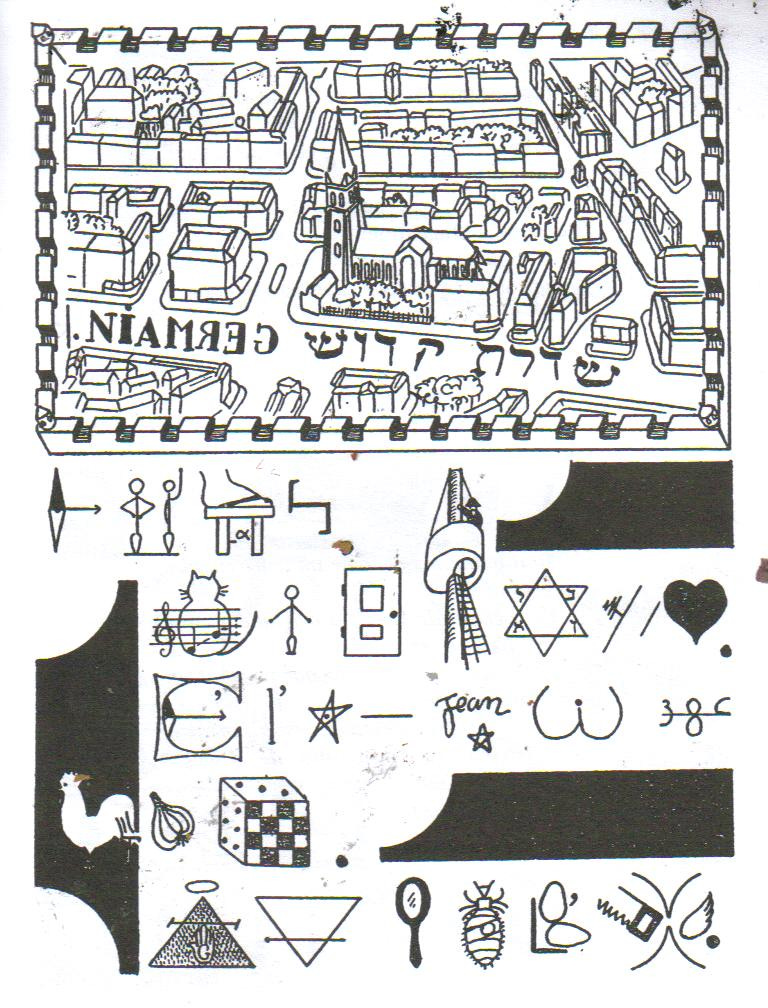

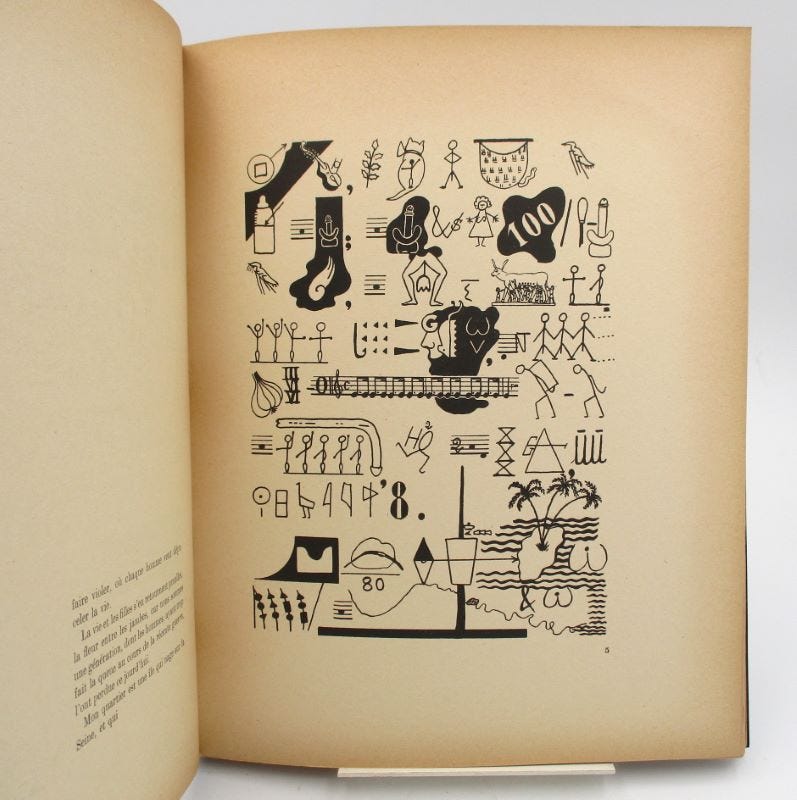

Saving the ‘Translator’s Afterword’ for later, Hugo Pictor tried to orientate from the text alone. Looking at row after row of visual figures recalled E. A. Wallis Budge’s transcriptions of The Book of the Dead. Had Pomerand seen these? Or galleries of Egyptian antiquities in the Louvre? Actually, the first drawing (below) offers an aerial view of Saint Germain des Prés as a Medieval walled city. Streets and buildings appear in outline at a vertiginous perspective, close enough to the restless twisting and linear sequencing of forms in Pomerand’s hieroglyphs (see the bottom half of the same page) to suggest the later could also be a landscape to inhabit, or escaped illustrations of the Nouveau Petit Larousse Illustre.

Maybe, thought Hugo Pictor, Pomerand’s accompanying prose offered a speedy, associative, improvisational response to the images. But Pomerand wrote the prose poem first. The images are his fastidious translation of the text, recalling the history of rebuses in esoteric Renaissance satires and upper-class 18th century parlor games. As the Afterword clarifies: ‘his representations are so complicated readers would be quite at quite a loss if he didn’t [provide the source text]… matching the words and pictures remains challenging and fun.’ One helpful key of two visual details:

Little footprints, for instance, “pas” in French, regularly stand for the word’s homonym, the negative participle “pas”; the formula “H2O” [which is often written on the visual pages] —water is “eau” in French, pronounced like the English-language letter ‘O’—is used when that sound is part of a word.Thus translation and reading in English become, as the translators call it, ‘a ridiculous exercise’. However closely I tried to follow I could never stop feeling the visual figures offered a far more complex, fermentive, various account than the text, one that only reluctantly allowed a left-right, top to bottom reading.

Some of this energy remains accessible in the text, as a brief sample demonstrates:

Saint germain des prés is a drowned drunk

peacefully floating from one bridge to another.

It’s a mushroom vomited from fever and

Fargo’s lamp.

All the streetlamp are Americans.

When one bumps the lampposts they prattle in‘Yankee’ the text continues over the page. A mention elsewhere of Boris Vian sent me back to a Penguin Classics translation of Vian’s Froth on the Daydream (1970, in French 1947), where a scene in a bookshop includes a browse of the shelves looking for Jean-Pulse Heartre’s Breathing and Stuffiness, his opus on the common cold. Excitedly the customer sprinkles the page with white powder and examines it through a large magnifying glass to reveal the print of Heartre’s left index finger. The bookseller throws in a pair of Heartre’s trousers to make it even more of a bargain.

This irreverent, Ubu-esque, downright silly aesthetic applies to Saint Ghetto (as too it defined Patrick Modiano’s debut novel set in wartime, La Place de l’Étoile [1968]). Is Vian, like Pomerand’s text, depicting the psychic and societal confusion of the Nazi Occupation and its aftermath, far more chaotically and ambivalently than the Existentialism of Sartre and Camus? And to possibly find the aesthetic model for all that Parisian distress in a massive slab of Egyptian hieroglyphs in the Louvre, helpfully bypassing both Classical and Modern French art history to make its splendid point…

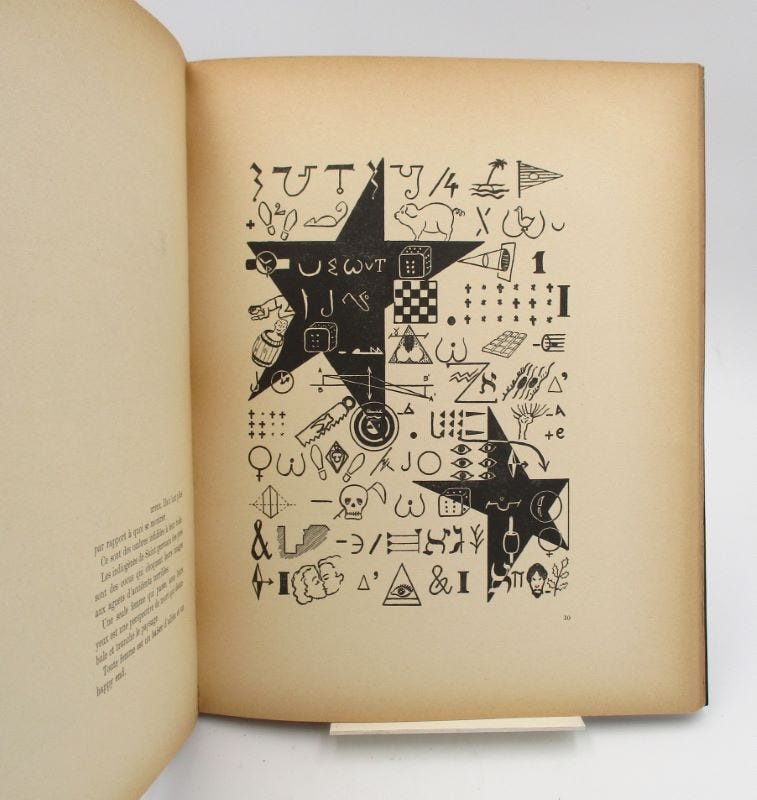

How does the text develop? Writing this initially from a PDF review copy I forwarded and reversed through the book, which emphasised its proto-cinematic effect as metagraphic grids shift from page to page. The background changes white to black as the book advances, initially via crosses, people, triangles, arms that energetically fill the whole space, overwritten with the graphics. All capture the unresolving rhythms of Saint Germain des Prés, mutable in a fevered authorial consciousness.

I use the word ‘code’ because I have been reading Johanna Drucker’s splendid review, which talks of the Lettrist project as ‘changing the very code of writing’ with its ambition (quoting Isidore Isou) to ‘tilt the history of literature from its amplic/expanding phase to its chiseling/condensing phase’. Such a shift applies to the reader, too, the behaviours that comprise their act of reading and any meanings that might be formulated.

Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire is not a text providing reassurance or resolution. As the penultimate page has it, Pomerand inhabits the utter vacuousness of ‘a neighbourhood specially built for the needs of foreign clients - like Venice for American tourists - for the currency needs of the temporally insolvent French Republic.’ He tells firefighters and machinists to ‘Carry off the scenery of Saint Germain des Prés’ and on the last page observes that as the only one left he is:

…down on my luck, all alone like a dog howling at death in the solitude of an empty desertI ponder the accompanying final page of visual symbols. That solitude of the desert seems to be translated into a public monument resembling a penis surrounded by an assemblage of ‘yellow’ Jewish stars and Christian crucifixes, recalling the poem’s opening that told us ‘Saint Germain des prés’ is a ghetto./ All there wear yellow stars on their hearts.’ I feel a bit humiliated by my simplistic reading. Then Pomerand signs his name below: what a strange, twisting, clear, indecipherable metagraphic that is.

For reasons Hugo Pictor could not quite fathom, his reading of Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire rekindled his passion for Peter Paul Rubens. For a while, quite recently, Hugo Pictor had collected books on the artist. Maybe it was The Making of Rubens by Svetlana Albers that started it, or the Wallace Collection publication Rubens: The Two Great Landscapes by Lucy Davis, which recalled the famous basement gallery face-off of 2020, or the Getty’s book on Rubens: Picturing Antiquity.

Hugo Pictor bought what old catalogues he could, eyed enviously the vast critical enterprise of Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, which commenced in 1968 and still has many volumes to go. Or a more recent The Drawings of Peter Paul Rubens, A Critical Catalogue, itself extending into multi-volumes each of multi-volumes. There was a point when you realised there were just too many catalogues of Rubens to allow even a whiff of comprehensiveness into one’s creaking shelves (Shelves?).

Far better, of course, to do a Rubens tour of London, which is where the connection to Situationist Paris sort-of came in. Go Rubens to Rubens to Rubens: there was Clara Serena Rubens, the Artist's Daughter at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, the beautiful friendship painting of The Family of Jan Brueghel the Elder at The Courtauld Gallery, the astonishing landscapes, again, of The Rainbow Landscape at The Wallace Collection and The National Gallery’s A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning.

Off Trafalgar Square, too, there was a Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs, attributed to Anthony van Dyck, but such a dérive was always going to step into the murk of attributions. It was Alpers’ argument that Silenus held a totemic place in Ruben’s psyche. Exhaustingly nice that central London was as heavy with Rubens as a spilling over-stuffed cornucopia at a bacchanal.

How did he do it? Even John Berger, in a grainy Ways of Seeing episode on YouTube, says sternly and charismatically that all oil painting is ownership, that landscape gets reduced to property by capitalism, but he has to admit that Rubens is just so brilliant that it transcends all this, gives us, beyond that, the world, despite the fact that Het Steen shows Rubens painting the view from his enormous house (Hugo Pictor didn’t go back online to find Berger’s actual words, he was sure he’d remembered it right).

With Rubens there is always more. Did he really give The National Gallery Minerva protects Pax from Mars as a gift to King Charles I when he was on diplomatic duties for Philip IV of Spain? (yes). I have never seen The Rubens Ceiling at the Banqueting Hall on Whitehall. The only way to see it is an occasional guided tour or hiring the whole venue for your corporate banquet. That ceiling, remembered Hugo Pictor, was the subject of Rubens and England by Fiona Donovan, the last book on the painter he had acquired, in Oxfam on Bloomsbury Street, that winter day when he abandoned bookselling… forever?

Hugo Pictor had gone to Buckingham Palace after that, for the one and only time, seen Ruben’s Self-Portrait in The Queens Gallery (usually it hung out of sight in the Picture Gallery). It was mad to object so much to connections of art with money, aristocracy and royalty, and still have Rubens as your favourite artist, but that was what he did to you, to them, to me, to everyone, thought Hugo Pictor. There should be scores of strange poetic essay-fiction-poem hybrids about Rubens. Hugo Pictor went through the book pile and could not find a single one. Did Jakob Burckhardt’s Recollections of Rubens count? It was a little long.

Hugo Pictor would have to dream it into life. Meanwhile, Rubens and Women opens at Dulwich Picture Gallery on September 27th. There will be a catalogue.

Hugo Pictor’s one-person Miniature-ish Book Club has been hanging out with his Antonin Artaud in English Translation Collectors Circle (member: Hugo Pictor).

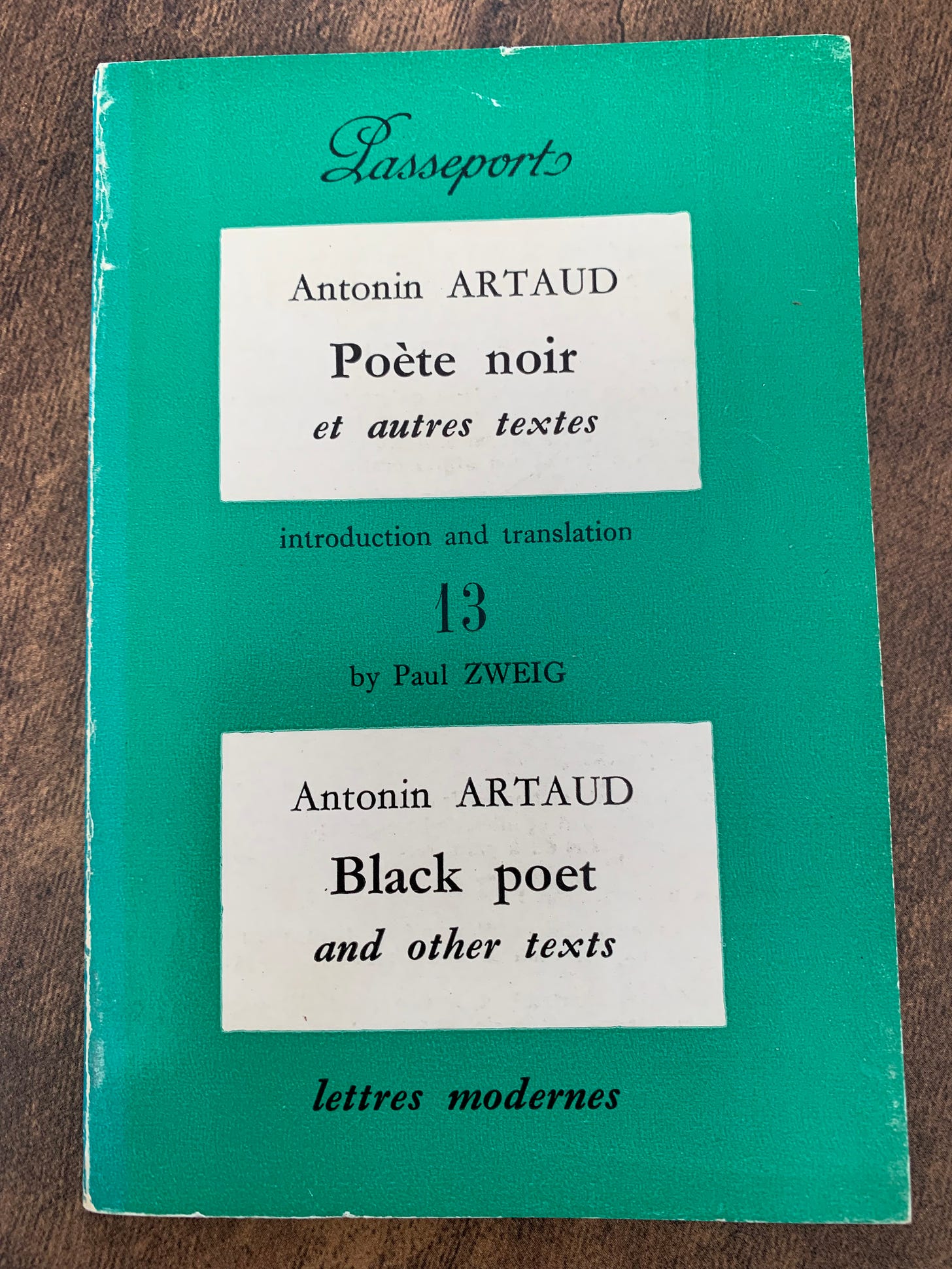

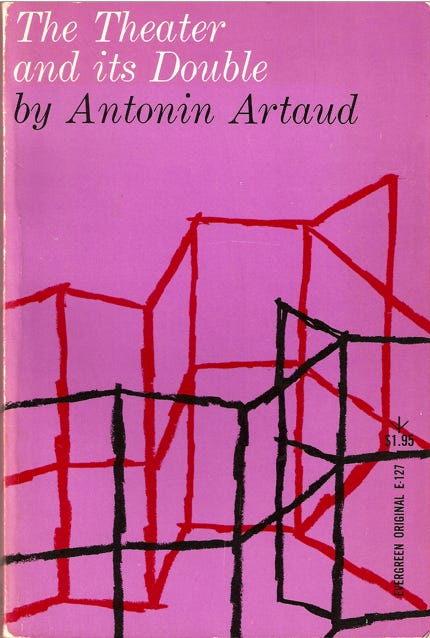

Paul Zweig’s translations seems to have been largely omitted from the historiography of Artaud in (particularly American - ) English, which focusses on M C Richard’s 1958 translation of Theatre and its Double, and Jack Hirschman’s 1965 City Lights Artaud Anthology, before Susan Sontag arrived in a 1988 Selected Writings. Zweig must have worked on the translation whilst at the University of Paris studying for his PhD in Comparative Literature. He later wrote poetry and memoirs as well as a study of Walt Whitman, before his early death aged 49 from lymphatic cancer.

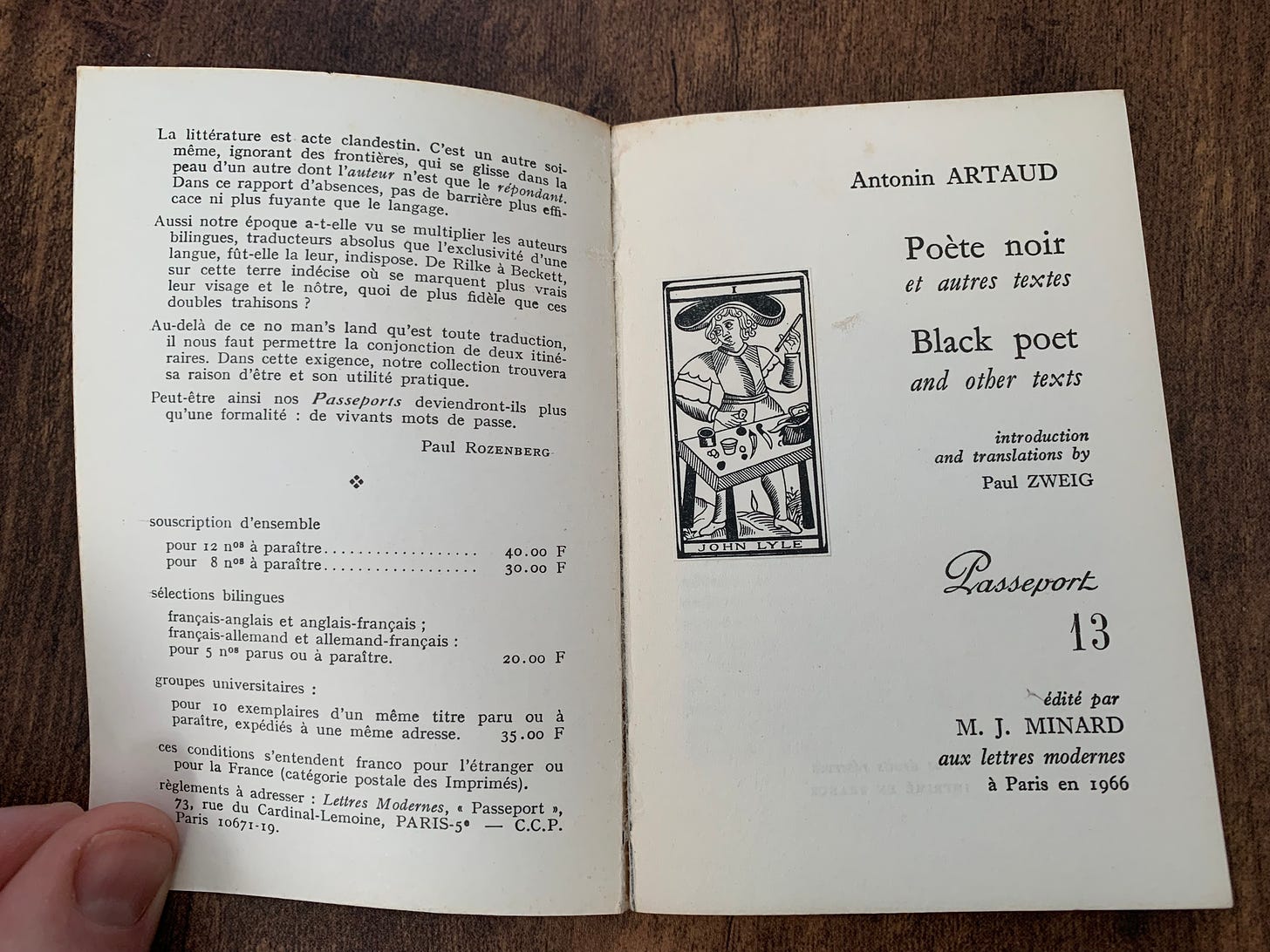

Praised as a poet by Robert Bly, Zweig was a student and teacher at Columbia alongside Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun. Different social and professional circles, perhaps, from those Black Mountain and Lower East Side artists and performers who most perpetuated Artaud in America. Zweig is unmentioned in Lucy Bradnock’s recent study of Artaud’s American influence, No more Masterpieces: Modern Art after Art, perhaps because of the (entirely European? France only?) distribution of Black Poet and other texts.

All of which is largely speculative, although Zweig’s book supports Bradnock’s broader argument of an array of Artaud’s traveling the (American) artistic landscape through partial translations of his writings and even vaguer - personal? - speculations at various removes about what a Theatre of Cruelty might be.

The image above shows one further connection to pursue, which is the book plate of bookseller and collector John Lyle, whose collection of Surrealist Books was auctioned in 2016. Having seen some of the book boxes after the sale, Lyle seemed a fairly committed Surrealist, so I was surprised to discover he was the subject of a diatribe 1971 broadsheet entitled No surrealism for the enemies of surrealism!, to be found in a digitalised version courtesy of The Met.

Lyle had reported shop lifters of surrealist volumes to the police, and our diatribe’s authors - an array of Surrealists in the US and Canada, plus Conroy Maddox in the UK - comment: ’this police action alone is sufficient to situate Lyle completely outside the surrealist movement’. But Lyle’s crimes also included ‘an impoverished manifesto’ entitled Surrealism Now, viewed here dimly as ‘an entirely retrograde mishmash of liberal platitudes which would hardly be out of place in the Ladies Home Journal.’

What did Lyle think of this? Perhaps he consoled himself with some lines from Zweig’s translation of Artaud, near the conclusion of the French poets Correspondence of the Mummy:

The voluntary mummy is awake, and around it all reality moves. And consciousness, like a touch of discord, runs over the entire field of its required potentiality.

There is a loss of flesh in this mummy; in the dark speech of its mindly flesh, there is an incapacity to do away with the flesh. The meaning that flows in the veins of this mystical meat whose every jolt is a manner of world, and a new sort of birthgiving, loses and devours itself in the burn of an erroneous vacuum.Lyle, like Hugo Pictor himself, felt invigorated. His mind whirled and he remembered that in 1965 the poet Alejandra Pizarnik had published The Incarnate Word, her essay on Artaud, in the Buenos Aires literary journal Sur. This, HP felt, was very significant.

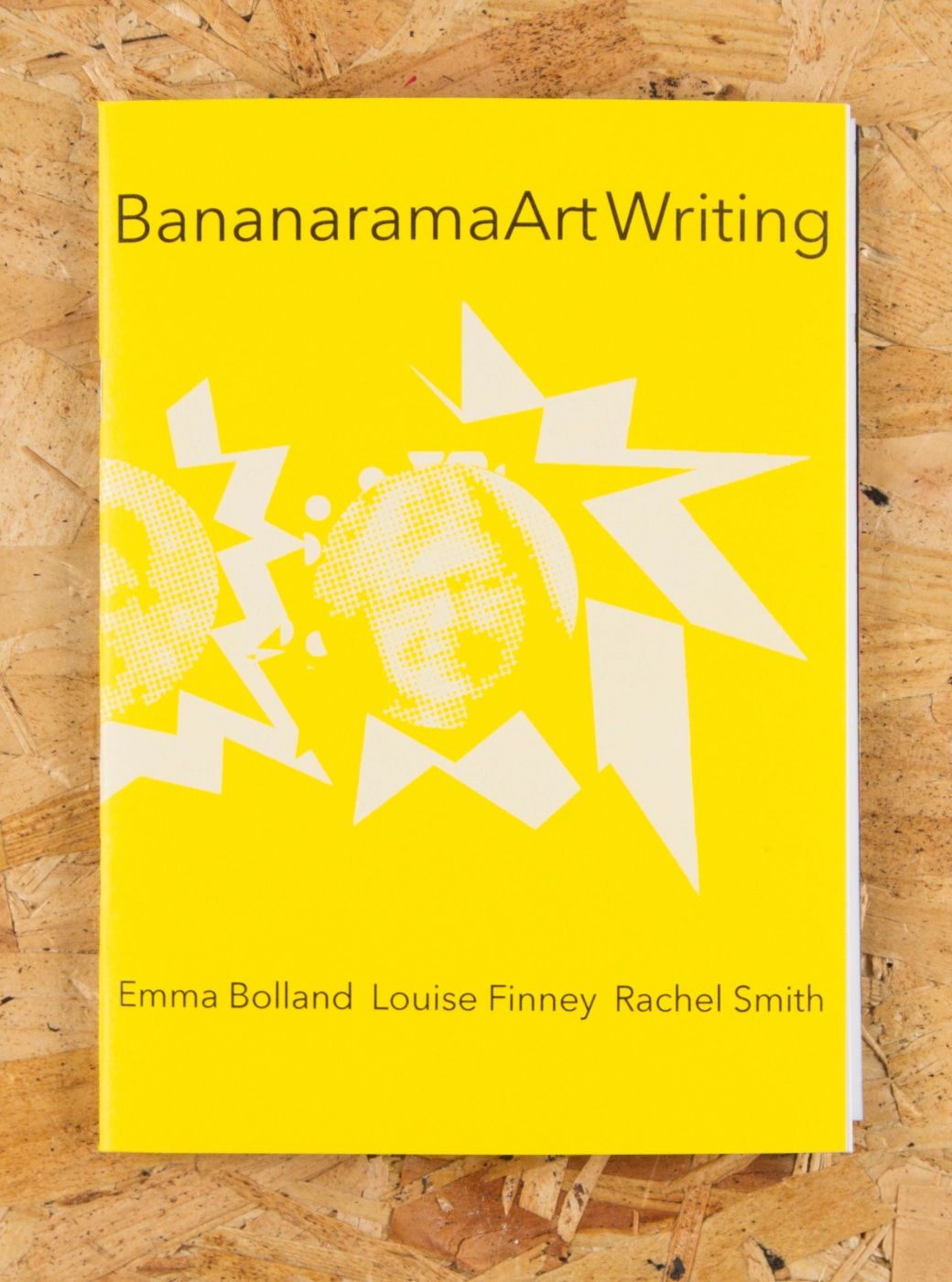

Finally this week, if Hugo Pictor fancied himself as the art book’s Peter Paul Rubens that still left room for Art Writing’s Bananarama, which was fortunate because he had come across evidence of such a phenomena in 2019. BananaramaArtWriting was a collaboration of Emma Bolland, Louise Finney and Rachel Smith, published by Gordian Projects, a press Bolland edits with Judit Bodor and Tom Rodgers.

It begins with a photo off the three authors holding cool drinks outside the Park Hill flats in Sheffield: ‘we look like the Bananarama of Art Writing’ says Emma. ‘Who are Bananarama?’ asks Louise. Each artist contributes one hybrid, typographically eclcletic text that weaves through one of the pop trio’s 1980s hit singles.

Bolland chooses Venus (noting she prefers the Greek form, Aphrodite). She quotes and strikes-through lyrics, picking out individual words and seeking new combinations and meanings. She begins with her response to a 1986 performance by the band. Then, after a personal inventory and invocation of the Goddess, it turns out we’ve arrived in 2017, the performer’s have become “Post-menopause succubae, gorgeously straddling their spectacle.” Maybe the pop lyric re-mixes and mythological trips are actually a fine way of reckoning the author’s (everyones?) last 30 years.

Finney, meanwhile, quotes the hit I Want You Back in a faint right-aligned grey text, whilst black type prose offers a sombre, more descriptive, paralleling account of a relationship breakup. Against pop brevity and pithiness, Finney offers an appendix with prose catalogue entries for the material domestic archive of the relationship: rug, ashtray, slippers, lamp. It goes both ways: the life that distills itself into the pop song, and the song that plays as the vastly more extended life unfolds in all its moods.

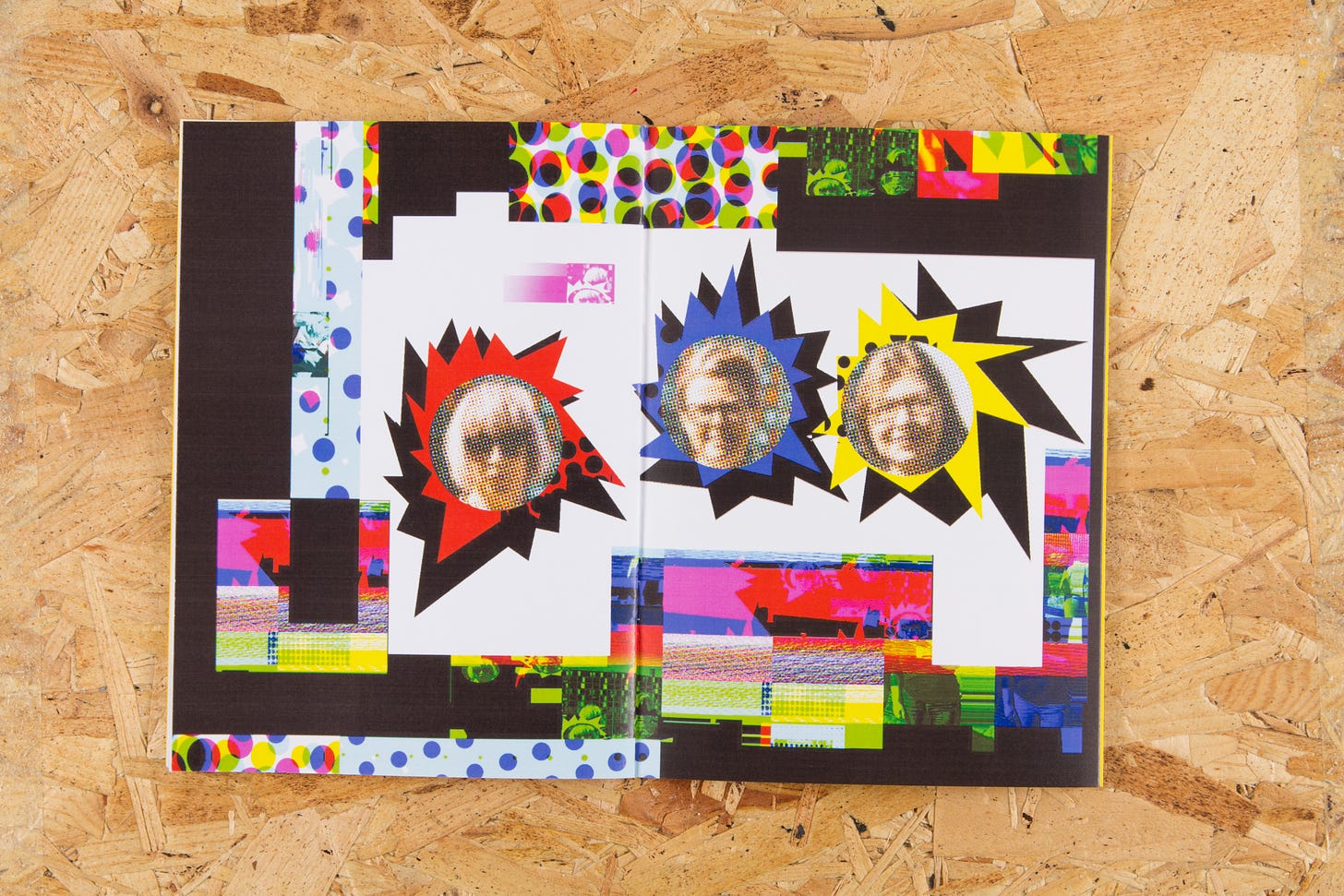

There is no dichotomy here of pop and art, and the pamphlet’s design absorbs text and author pics into a 1980s, Smash Hits, disco ball aesthetic. Smith’s concluding text makes Guilty Winter of the trio’s Cruel Summer, although Smith doesn’t stop there. Kissable Autumn? Condescending Spring? Each section of her text begins with a three line riff offering new adjectives for Autumn, Winter, and Spring, followed by a juxtaposition of song lyrics with what seems to be her teenage memories.

Formally I see Smith trying to match memory to the song lyric’s brevity and rhythm, but the stuff of her lines always both fits and jars, extending out of any looping, scanning, song-mnemonic. All three texts, then, move with the material, experience, memory, truth, foolishness and aura of pop, in and as our onward rushing lives.

Hugo Pictor was always looking for reading to have a concrete effect. And there he was, on his phone, watching Bananarama videos, before he unfolded something he wished every book had: its A3 pop poster. Where to go next? Hugo Pictor wasn’t sure of the chronology, but surely Kylie Minogue’s reading of I Should Be so Lucky as an experimental poem would never have happened without this pamphlet’s neon joy.