The Complete Hugo Pictor

Andrew Cranston, Miyiko Ito, Wendy Baron and Walter Sickert, Seven German Altars, Dirk Lauwaert, Memling & Bouts, Vakho Khetaguri, Sandra Johnston with Objects.

Hugo Pictor’s plan had been so clear: books that captured an artist’s whole oeuvre. To leave aside for a moment the excitement of first books, steps, researches. To go for the hard to lift catalogue raisonné summing up a lifetime of artistic endeavour. It seemed celebratory at first, then melancholic as Hugo Pictor lugged tombstone sized slabs of bookish mortality and memorialisation from The Pile.

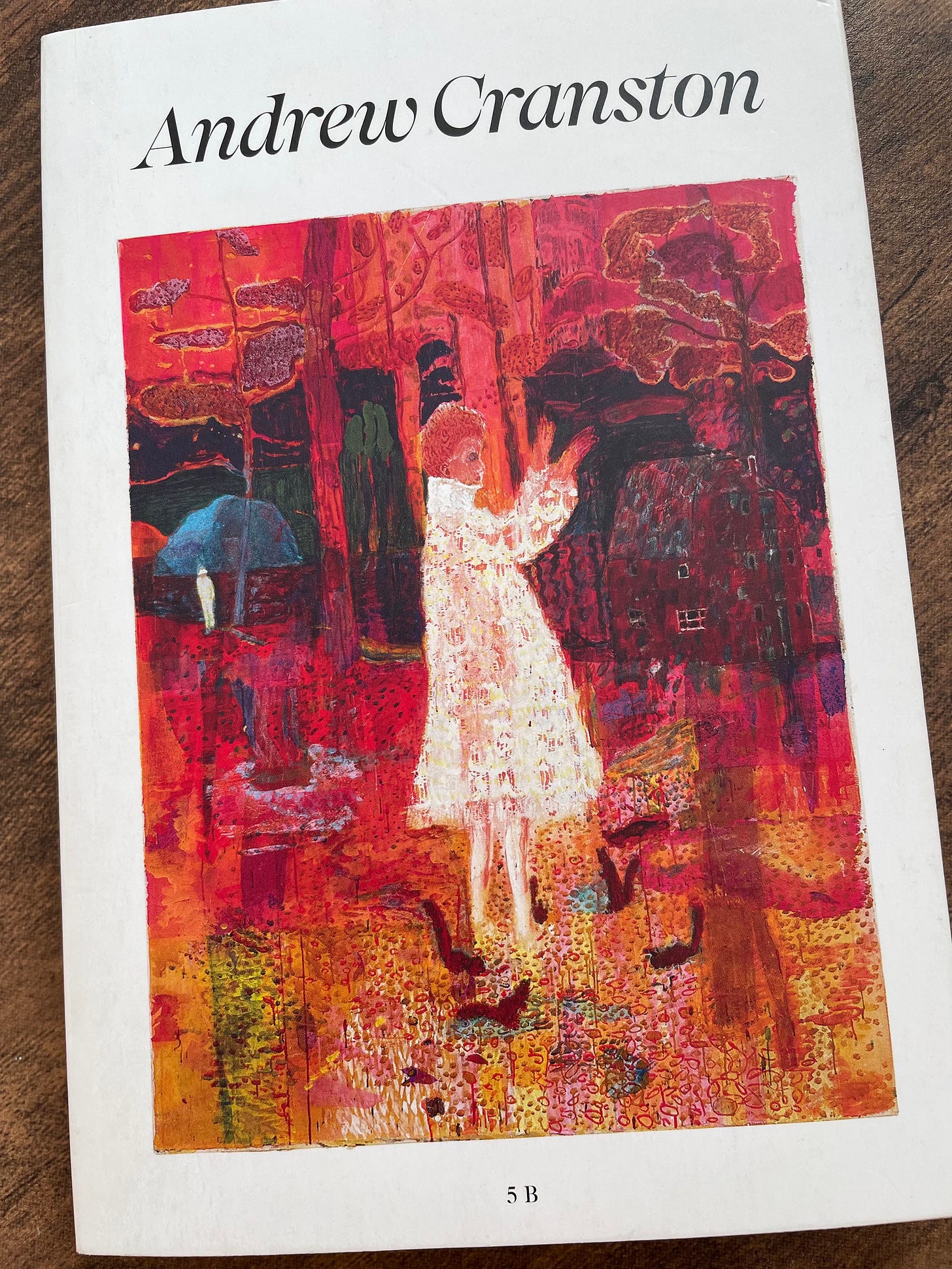

How, then, to proceed anew? Two books by and about Glasgow-based painter Andrew Cranston summed up decades of endeavour, whilst also having the energy of beginnings still ongoing (Why couldn’t Hugo Pictor find his way to Wakefield in time?). One was a monograph for 5b editions that copied the format of one of Cranston’s own favourite books: a Paul Klee volume in the Fontana Pocket Library of Great Art.

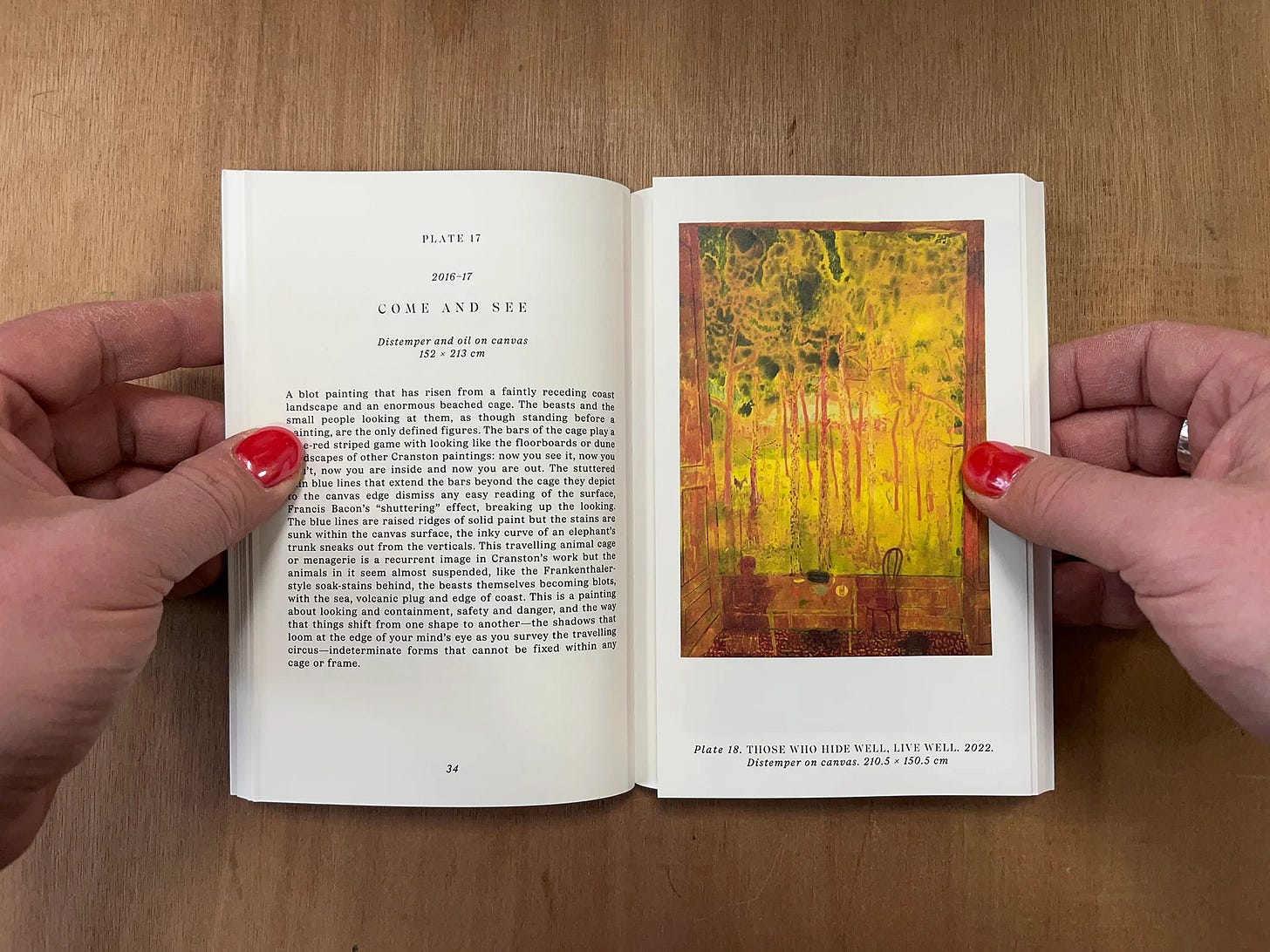

After an introductory essay by poet Olli Hazzard, the colour plates, some on fold-out sheets, got accompanied by page length commentaries by Liza Dimbleby. These seemed based on long running conversations with the artist ( Dimbleby wrote an essay for who is this who is coming? a 2015 Cranston catalogue from Aye-Aye Books), but they never let that override the mysterious ambiguity of the paintings.

Instead commentaries point out details that might be missed as a 240 x 180 cm canvas is compressed into A6 reproduction. They position a painting alongside art historical references (Bonnard, Matisse, Carel Weight…), and try to discern what, say, ‘awkward, ageing bodies on the rug’ might be seeking as they do their yoga (‘pursuing the ideal, but they remain part of the pattern ,finding their place in it’).

They also detail aspects of technique: paintings on book covers, bleached or dyed canvas, in oil and distemper, in rabbit skin glue. Forty paintings on a go at one time, with cats, pots, transparent legs, volcanic plugs.As Hazzard writes, paintings of:

moments of change. Small change (in bodily sensation, in mood, in daylight) and large change (in the trajectory of a life, in a person’s sensibility, in art history, in geographic formations).Hugo Pictor couldn’t find that Paul Klee pocketbook in The Book Pile, but it reminded him how, in If these Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, T J Clark had expressed his admiration for Meyer Schapiro’s Cezanne in a similarly low-cost mass-market Masters of Art series from Abrams. This format also put a page of commentary alongside each reproduction:

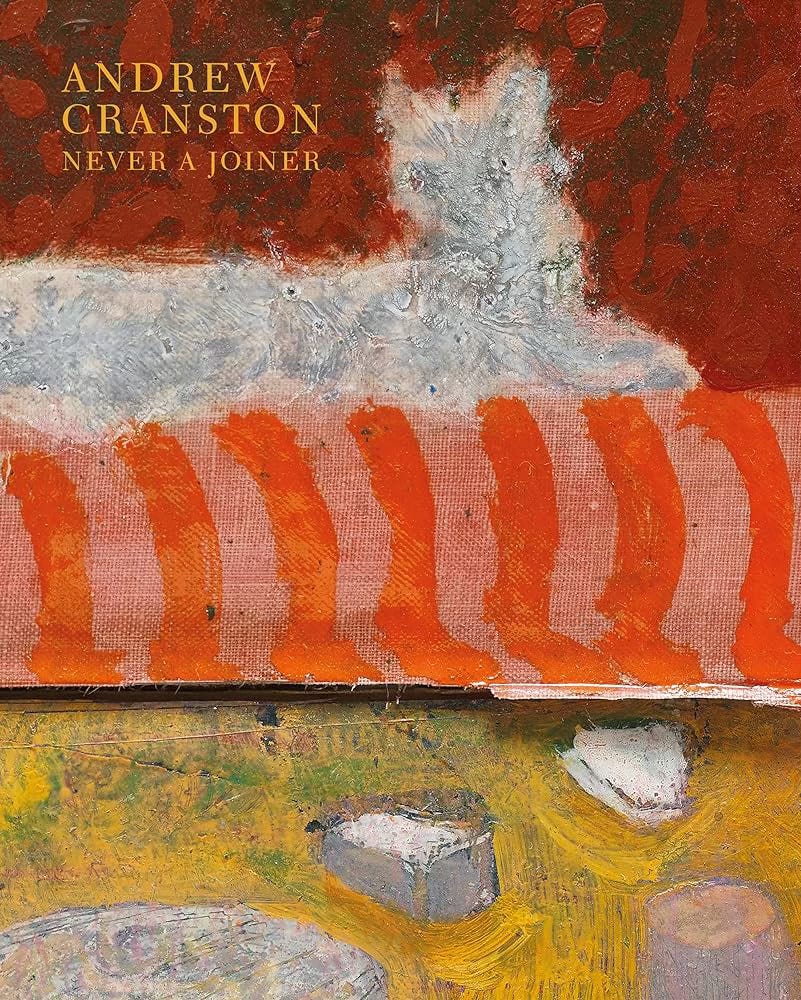

Clark noted that academic literature on Cezanne snootily ignored Schapiro’s book, although he found it one of the few helpful sources when writing his own. In the 2023 publication Never a Joiner, the texts alongside reproductions of Cranston’s paintings are by the artist himself:

About ten years ago, for my own uses and pleasure, I started to write about my work in a way that felt more like the freedoms I have always found within painting itself - something more playful, responsive, emotional, speculative, personal, creative. I write these notes during and after (and very occasionally before) making a painting. I never thought I’d be publishing them.Notes on paper scraps, index cards, a mobile phone. Fragments that ‘sometimes join up… sometimes don’t.’ Cranston likens this writing to album sleeve notes, or the introductions to poems of poets at readings. As he writes - keen for words to be an ‘aid’ when deciding ‘what to do next to a painting’ or figure its meaning - Cranston finds ‘de-mystification’ quickly leads to a need for ‘re-mystification’ and there quickly emerges ‘a fictional element… as if they are short stories or poems.’

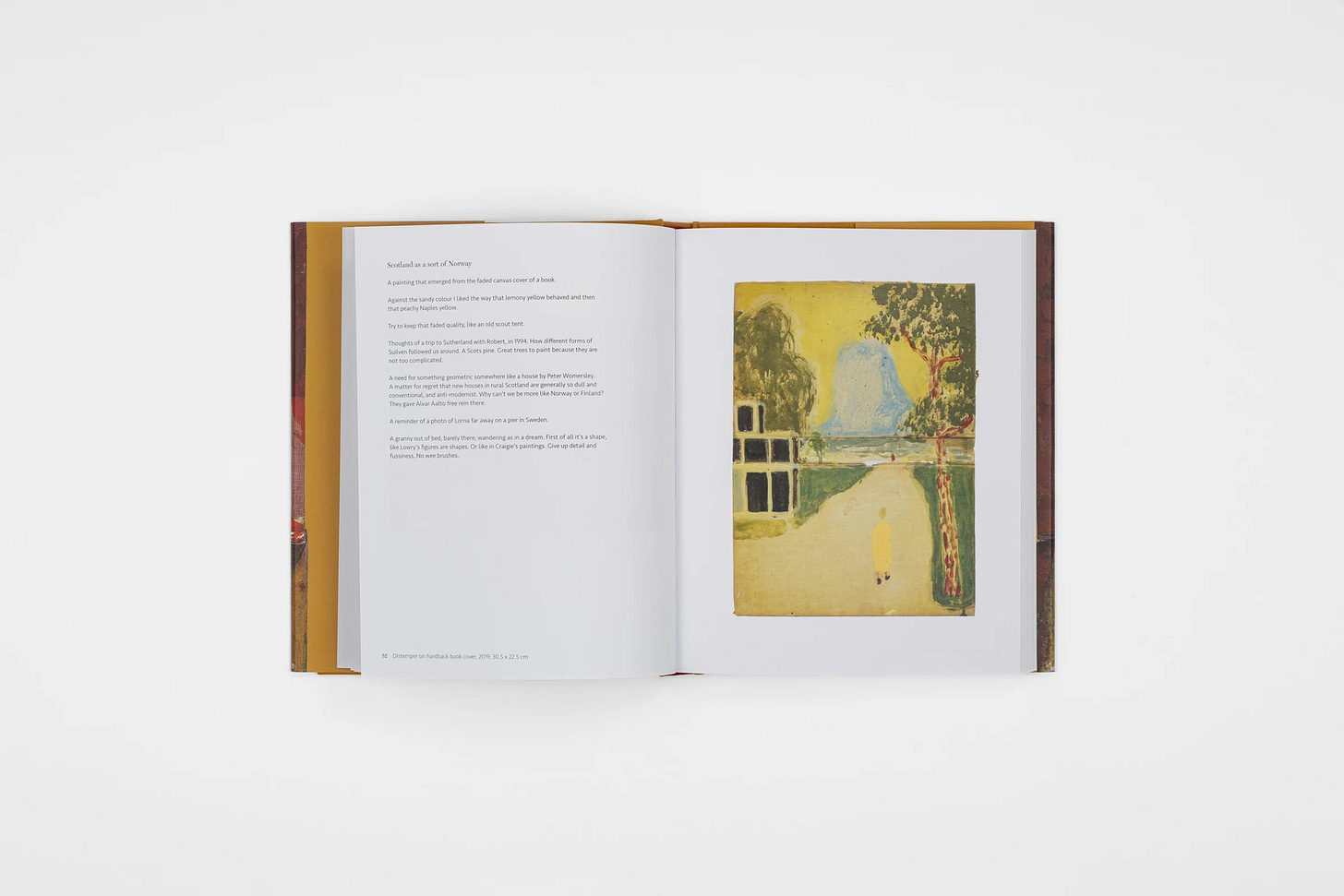

The works reproduced in Never a Joiner are painted on book covers, their forms emerging and mutating over months or years in the studio. On a few occasions, the book’s title is visible but the attraction mostly seems to be an aesthetic one: a bleached cover that he can accentuate and paint around, for example ‘a flea-bitten, faded and stained book lying on the floor of the £1 section in the Glasgow bookshop, Voltaire and Rousseau… unopened, unloved for years.’

A whole method of reading, Hugo Pictor felt, in how Cranston responds to a book:

I often feel I am drawing an idea out of the book itself, listening to it for clues and suggestions, following some lead it gives me. The book is more often a conduit for remembering, resisting experiences and memories. Nuts stored for the winter.So “The faded green [of that book jacket] led me to [remember] camping trips….” The combination/ encounter/ meeting with the book is necessary for anything to happen. Hugo Pictor eyed the tottering edifices of the Book Pile. Waiting, he murmured to himself. Meeting. Occasion. In combination. Camping. Happening.

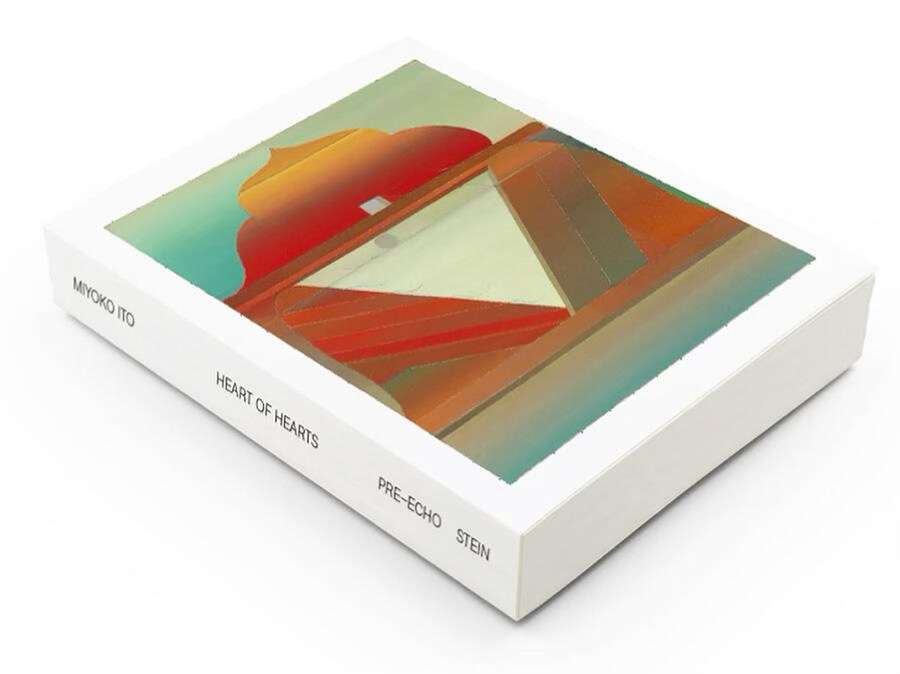

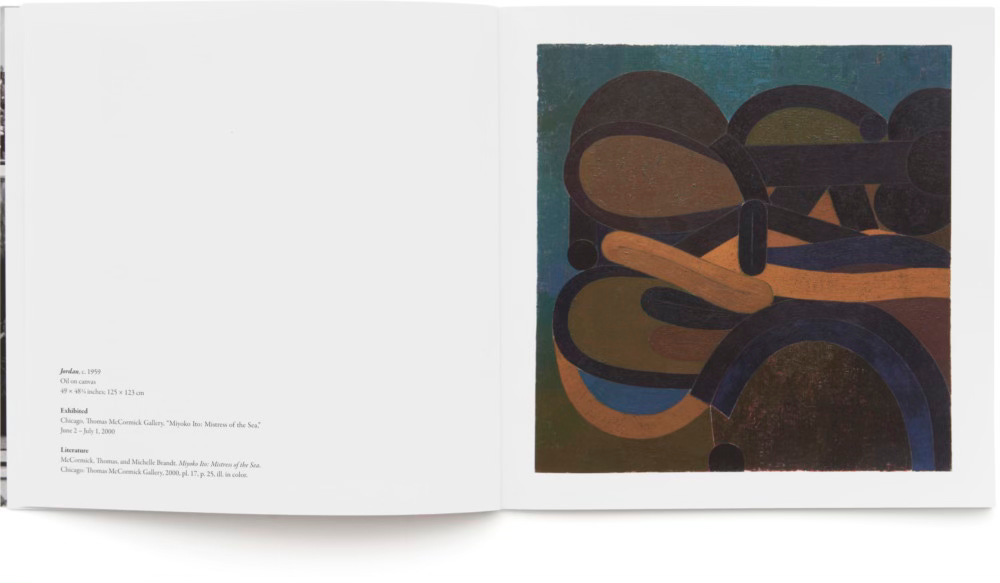

Other times, Hugo Pictor wanted a huge monograph like a fridge door. This desire was satisfied by the 454 pages of Miyoko Ito Heart of Hearts. A chronologically arranged 300 page plate section offered full page reproductions of Ito’s canvasses, occasionally interrupted by full-page details of brushwork.

All bookended by Jordan Stein’s introductory essay, whilst at the rear: an interview with the artist, ephemera of artist statements and gallery brochures, installation shots of two solo exhibitions. Heart of Hearts, Stein says, is neither catalogue raisonné nor museum monograph but ‘a rather straightforward accounting of all the mature works that we could find, as well as several of her early works in watercolour, lithography, and oil that set the stage for her extraordinary development.’

Stein’s essay provides the biographical and contextual basics. Born in America in 1918, brought up briefly in Japan then back in San Francisco before, like many Japanese-Americans, being incarcerated in internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbour. Ito made a career as an artist in Chicago. UK readers might find resonances with recent exhibitions and catalogues of Chicago Imagism and Forrest Bess. Ito was friends and sometimes collaborator with the former group, whilst shares with Bess a personal language of forms whose abstraction is landscape, object, psychology, self-portrait (Ito also mentions Giorgio Morandi as a favourite artist).

Stein’s essay refrains from analysis of any single painting, but is astute summing up periods and series, as when describing Ito’s work after the late 60s:

Whilst references to landscape painting and architecture are overt, Ito’s highly-structured yet never-quote symmetrical compositions map a psyche that oscillates between feeling confined and expansive. In a palette that warms throughout the decade, vertical stacks of tubes, bars, and mounds are rendered in delicate fades of colour and subtle modulations of tone. From these paintings, a picture emerges of a formidable artist positioning her art in relation to her inner and outer worlds, hard at work to summon painting not only as a network of signs but also as a sign unto itself- personal, complex, and resonant.Hugo Pictor stared at the final page: a painting left unfinished when Ito died in 1983. It showed Ito’s method of painting into a structure outlined in pencil. An apt image, too, for this book’s achievement: a detailed underdrawing for future research and looking.

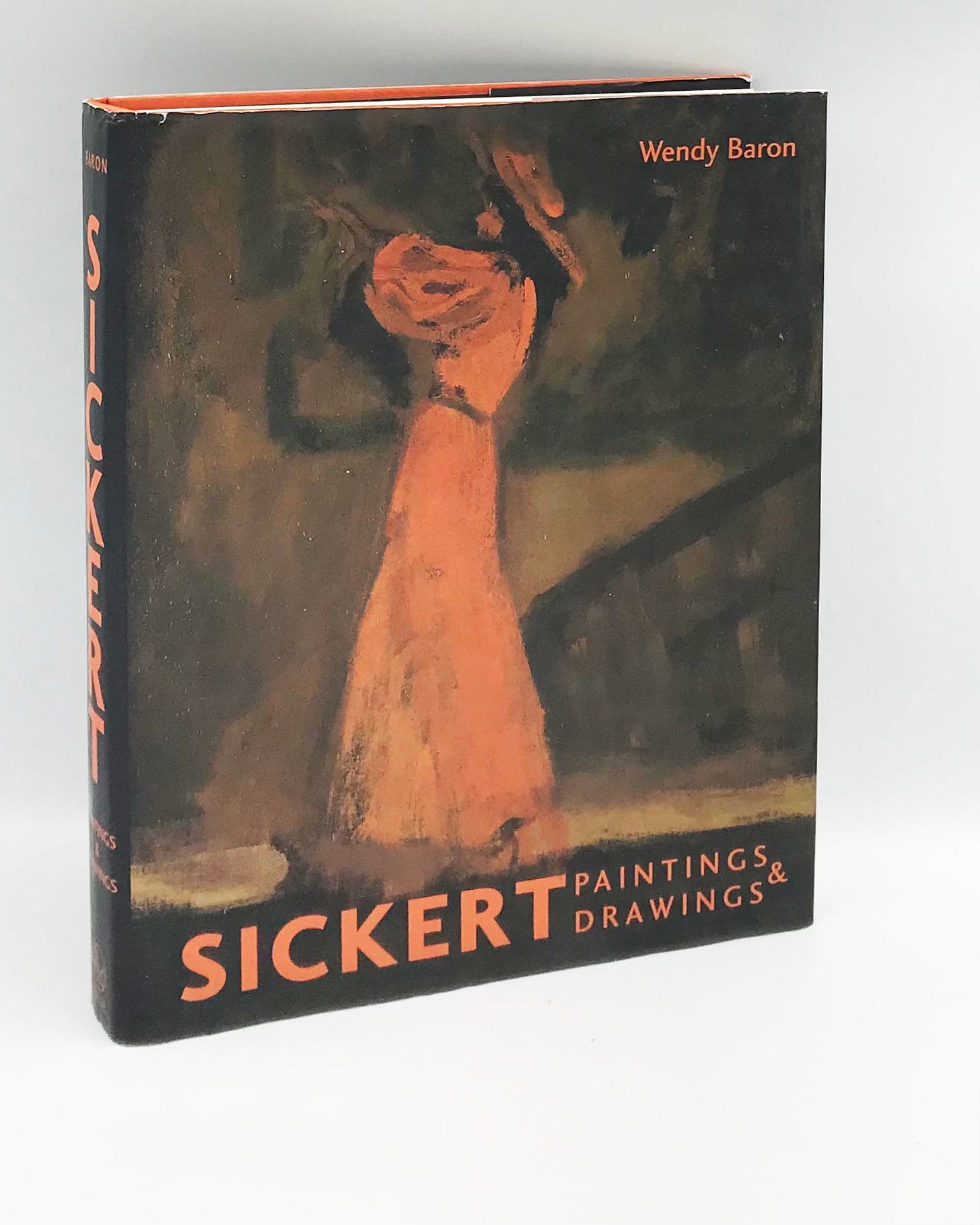

Hugo Pictor was sometimes drawn as much to compiler as subject. A passing remark by Cranston about Walter Sickert (his detailed Tate talk about the artist's technique, prompts the audience question: ‘Was Sickert Jack the Ripper?) sent Pictor back to Wendy Baron’s monumental Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, its second and (so far?) final edition of 2006.

In a recent essay ‘A Life with Sickert’ Baron narrates her life-long engagement with the artist, beginning in 1954 as a teenager watching a TV documentary on Sickert in a hotel lobby in Margate. This was followed by a student project at the Courtauld. Even at that early stage Baron says she realised questions ‘about the chronology of his work; his enigmatic subject matter; his handling of paint; the impossibility of fitting him into any conventional school or group… [that mean] sixty years later my task remains unfinished.’

Baron became friends with an earlier generation of writers on and curators of Sickert, such as Lillian Browse; his surviving friends, students, private collectors. A grant in 1959 enabled her to travel the UK, documenting the many Sickert works dispersed to regional museums and collections. This informed a PhD, and a book on Sickert’s friend Ethel Sands, whose letters from Sickert Baron borrowed and copied by hand.

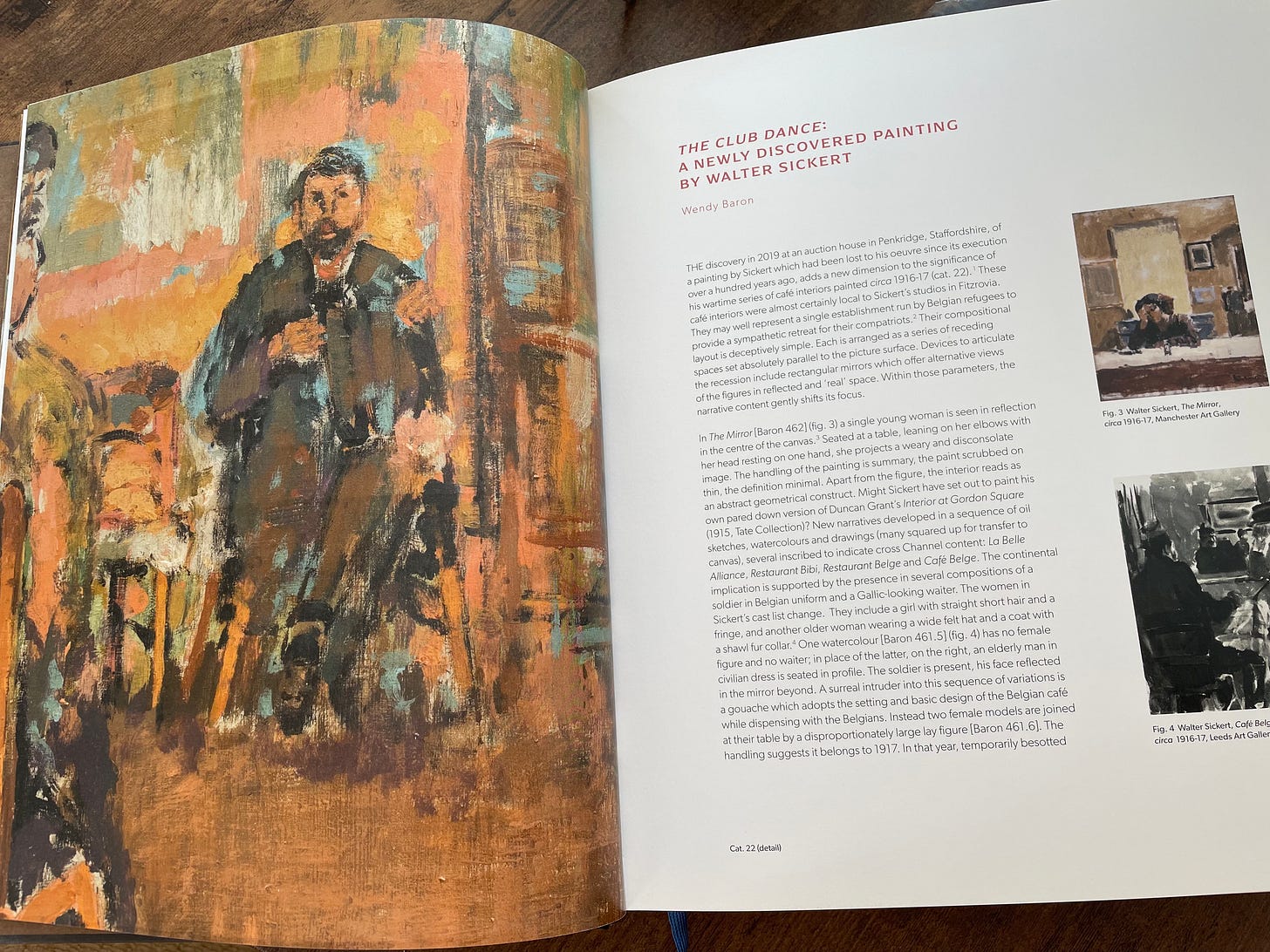

Studying Sickert meant following the artist’s paintings that appeared in almost every auction of 20th Century British Art. The 2021 catalogue in which Baron’s memoir appears - Walter Sickert: The Theatre of Life- includes her study of The Club Dance, a Sickert re-discovered in 2019 at an auction house in Penkridge,Staffordshire.

‘Have I ever regretted my life with Sickert?’ she asks herself. ‘No, I am still in love with him.’ His uncensored production, his professionalism, plus ‘He is never boring…always experimenting and evolving his style and practice.’ It was tempting, thought Hugo Pictor, to see Sickert: Paintings and Drawings as a fastidious construction of objective fact, reliant, as Baron observed, upon “old-fashioned art historical methods” to postulate a chronology from Sickert’s largely undated paintings. But Pictor noted Baron’s Foreword ended with a rebuttal to emerging methods of New Art History:

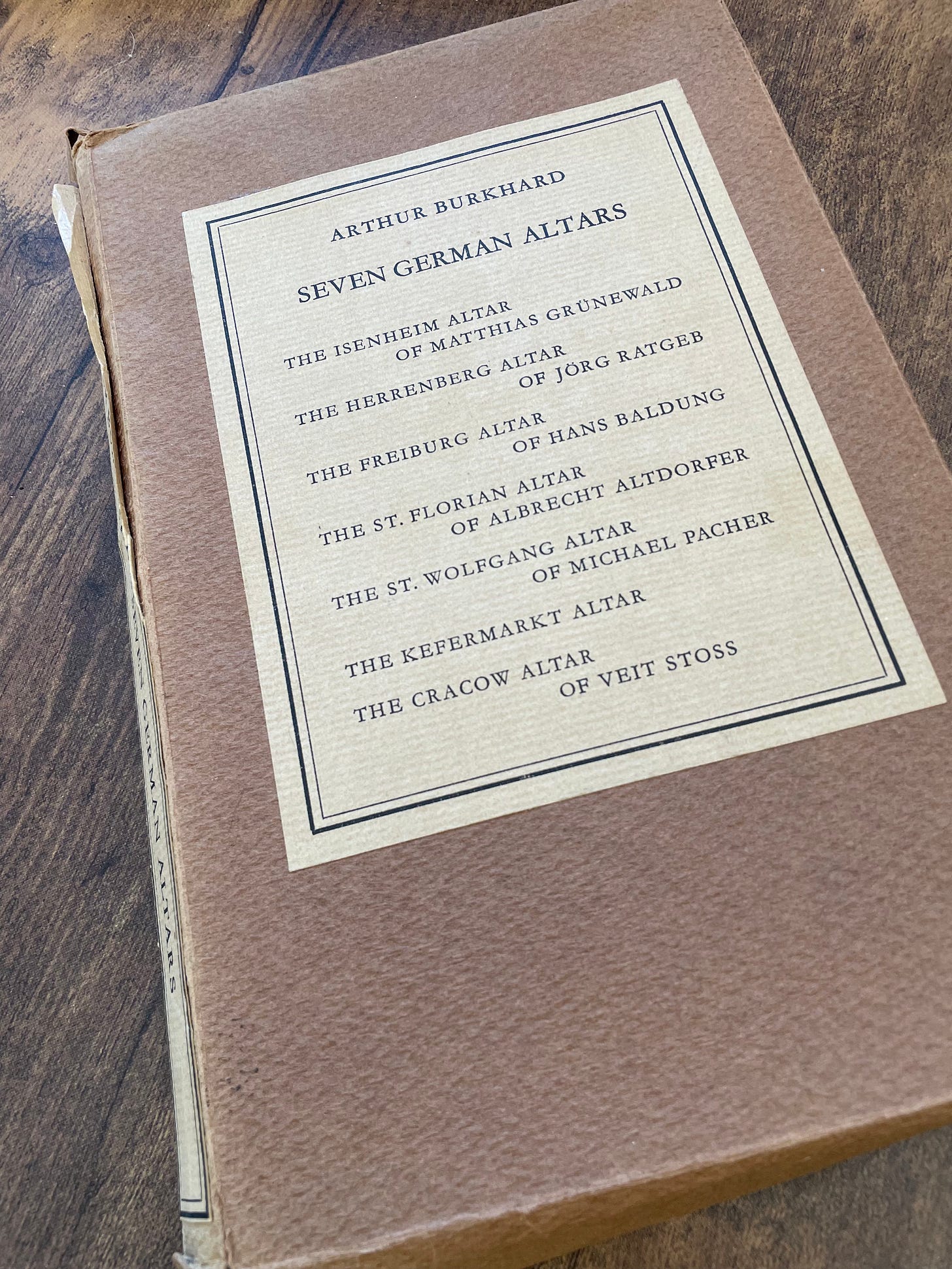

I feel no temptation to interpret his work from a sociological, Freudian, feminist, Marxist, or twenty-first century standpoint. Rather, I have tried to mirror Sickert’s own perspective: that of an an artist wrestling with an intractable medium to express, with uncompromising truthfulness, the beauty which his unique vision revealed in the squalid as in the sublime.Was it too late for Hugo Pictor himself to embark on such a project? What or who would be the subject? Himself? Hugo Pictor thought that might be a joke. What form would his research take? Would he be a Marxist? Helpfully a few moments exercising in front of the Book Pile turned up Seven German Altars (1972) by Arthur Burkhard.

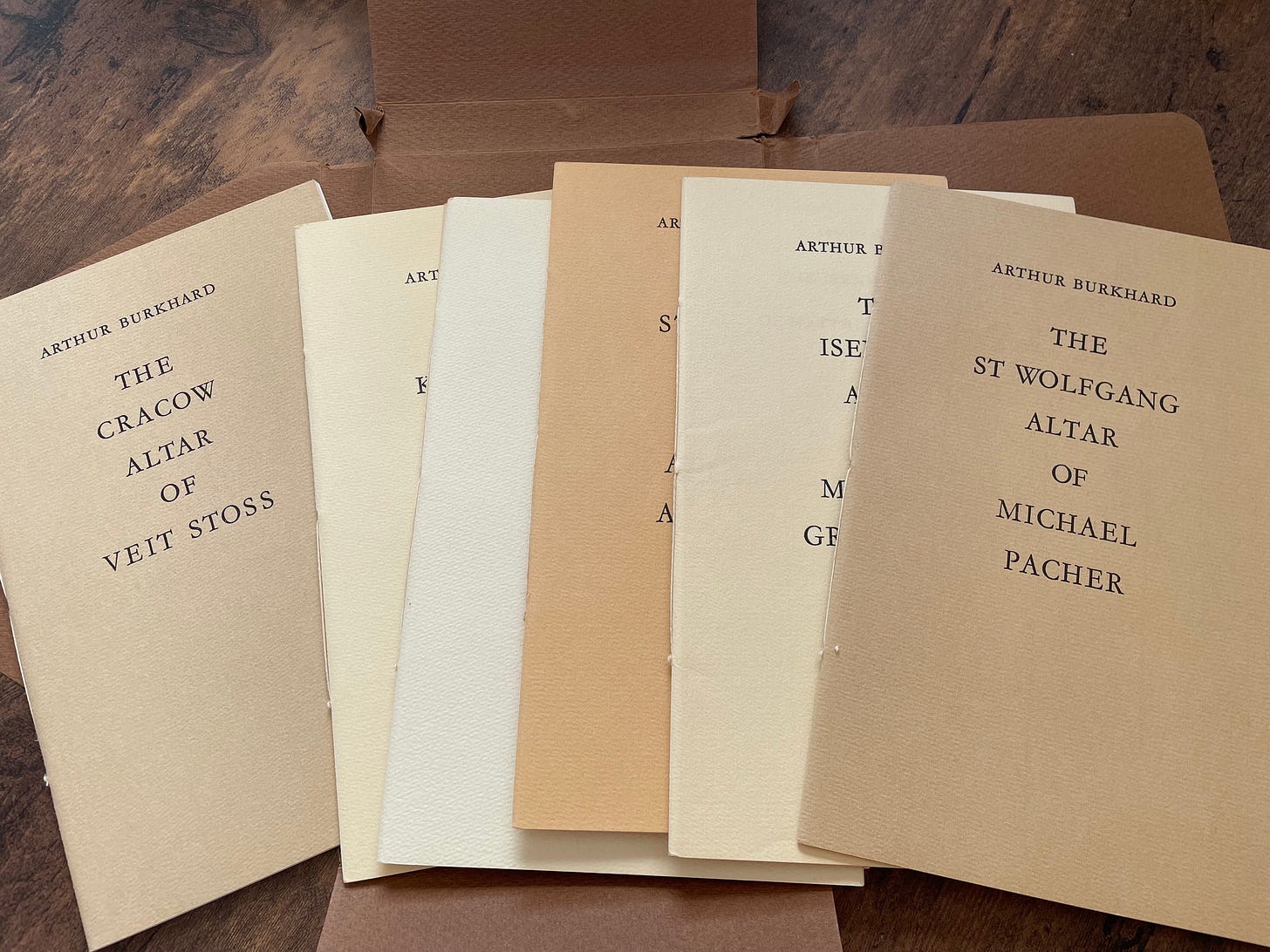

Said like that Seven German Altars could sound like an oblique, lost bookwork of early American Conceptualism. It gathers seven of the art historian’s essays as a uniform series of sewn-stitched pamphlets. One is an off-print from Speculum, others seem written and typeset specifically for the publication, self-published from the author’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, February 1972, with help from a Munich printer.

Two dedication pages reveal the project as a summing up, a distillation of the scholar’s thoughts and debts, a model of self-published scholarly summation:

Hugo Pictor was struggling to focus. There were surely other volumes on Medieval German altars it would be useful to discuss. But his fingers did something automatic on Google then he was looking at Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Colour, Join, Face (2023) by Julia Bryan-Wilson where each of those sub-titles was its own separate volume in a Burkhard-Gasteiger style slipcase.

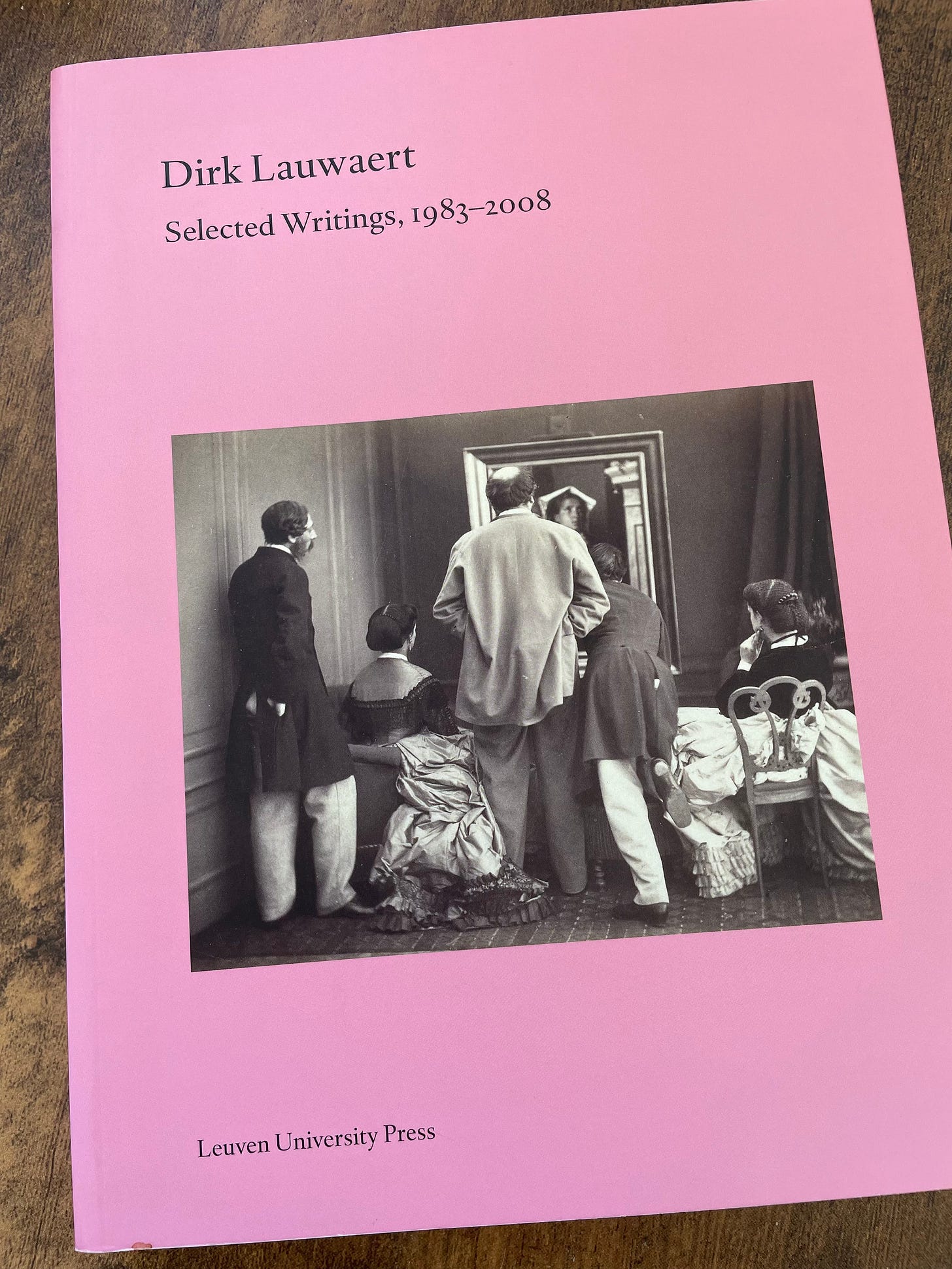

Hugo Pictor was excited to imagine innovative forms of publication for personal essay projects he hadn’t even conceived of yet. He remembered Dirk Lauwaert. In his lifetime, in Holland, in Dutch, Lauwaert was prolific. Thousands of texts, including autobiography, a continual stream of book, film, exhibition reviews. In English, though, in this Selected Writings, 1983-2008, Lauwaert was distilled into fifteen essayings.

Here the critic of occasion and event - the new film, the new book - is replaced by a thinker more attuned to underpinnings of thought and critical practice. Essays on Enthusiasm, the rhythm of thinking itself, ruminations on ‘thinking forms’ of seam and pattern, on Roland Barthes, who this new concentrated Lauwaert strongly resembles. Lauwert knew this well, for his essay here on the French thinker begins:

One does not write about Barthes but along with him. One does not put oneself outside of him, but adopts his forms, even if one does not share his arguments. He commands an irresistible form of mimetism. Thinking here inevitably takes the form of a relationship. The ample white space at the foot of each page performs the gaps, rhythms, and stops that come from thinking, as in some essays here, in numbered paragraphs.

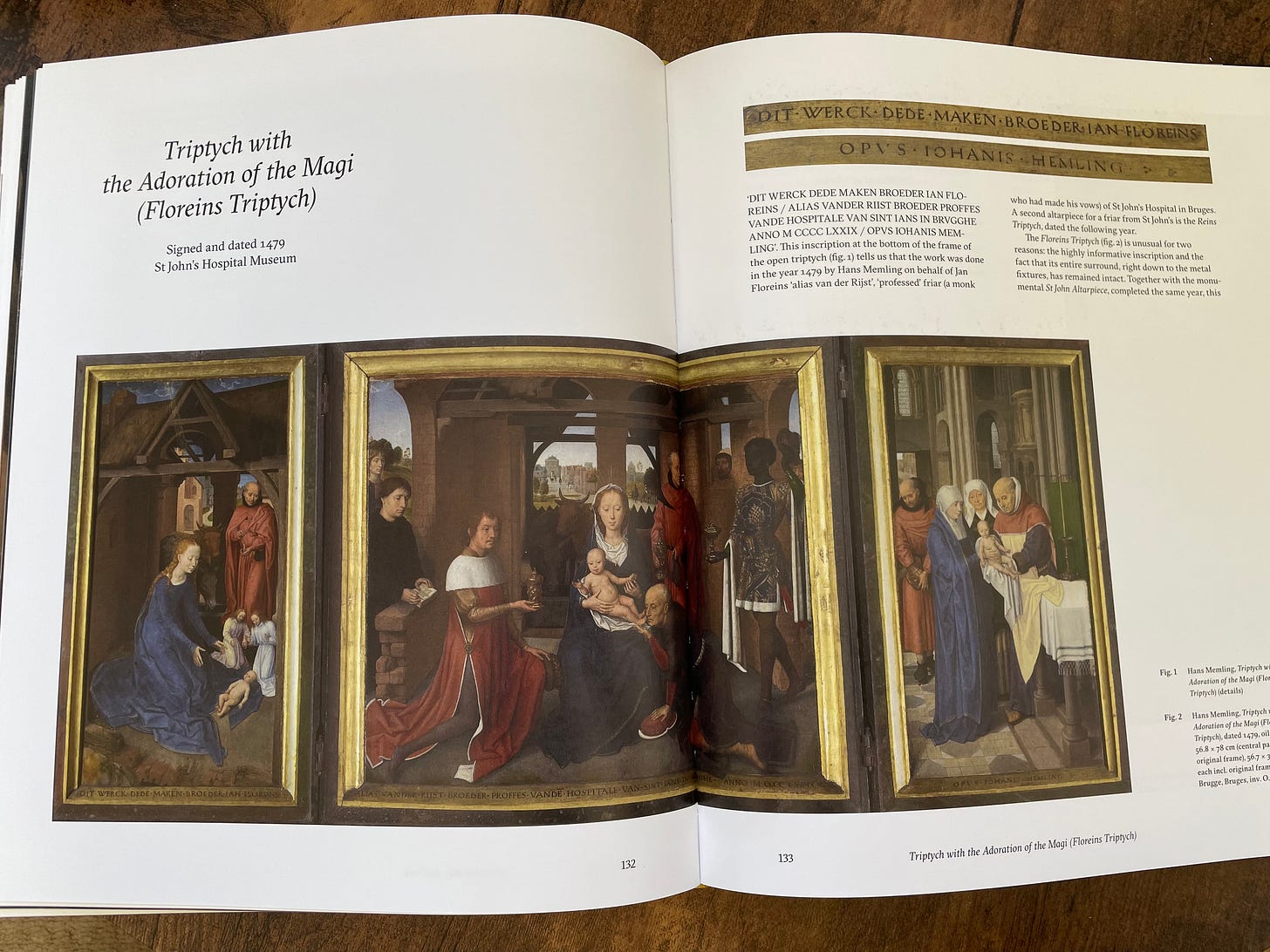

Hugo Pictor closed his eyes. Instead of coloured boats of psychedelic photopsia, his eyelids hosted a reproduction of a Hans Memling altarpiece. Not entirely unexpected, for Pictor had been up at dawn enjoying Memling in Bruges, a catalogue for a show focussed on paintings Memling produced for his adopted city, many of which remain in their original home of the St. John’s Hospital.

Curator Anna Koopstra’s text offered an overview of Bruges, the hospital, Netherlandish art, Memling’s life and career. It pondered Memling’s connections to contemporary artists (the original show included a display of Kehinde Wiley paintings), although a recent catalogue for fellow Netherlandish painter Deiric Bouts is more explicit here. Its essays connect the ‘reality effect’ of Bouts’ paintings (water stained walls, a cracked floor tile, a creased cloth) to the creation of ‘immersion’ in game design, or use a ‘trans-historical’ approach to place Beyonce singing at the 59th Grammy Awards alongside Bouts’ Virgin and Child seated in a stone niche.

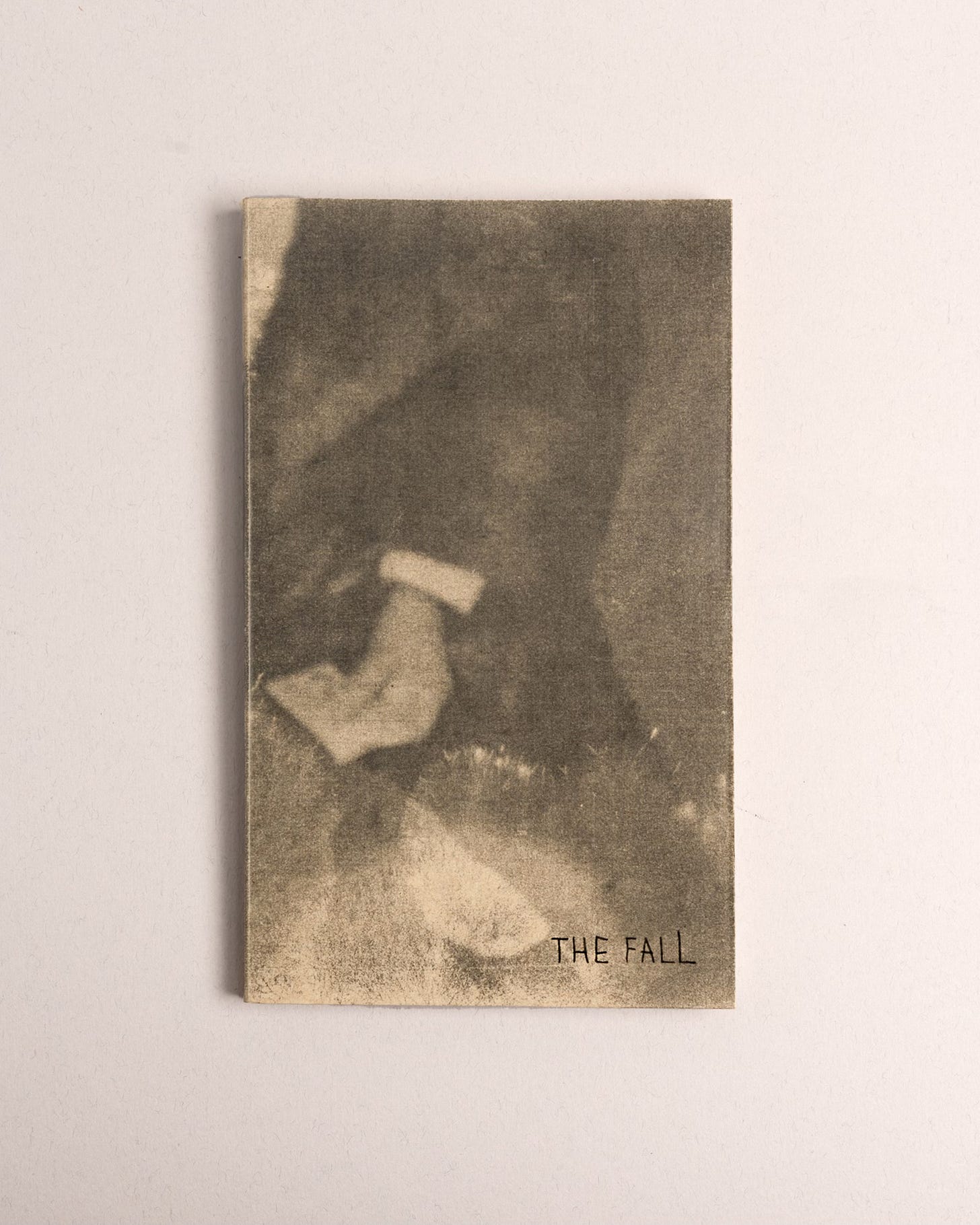

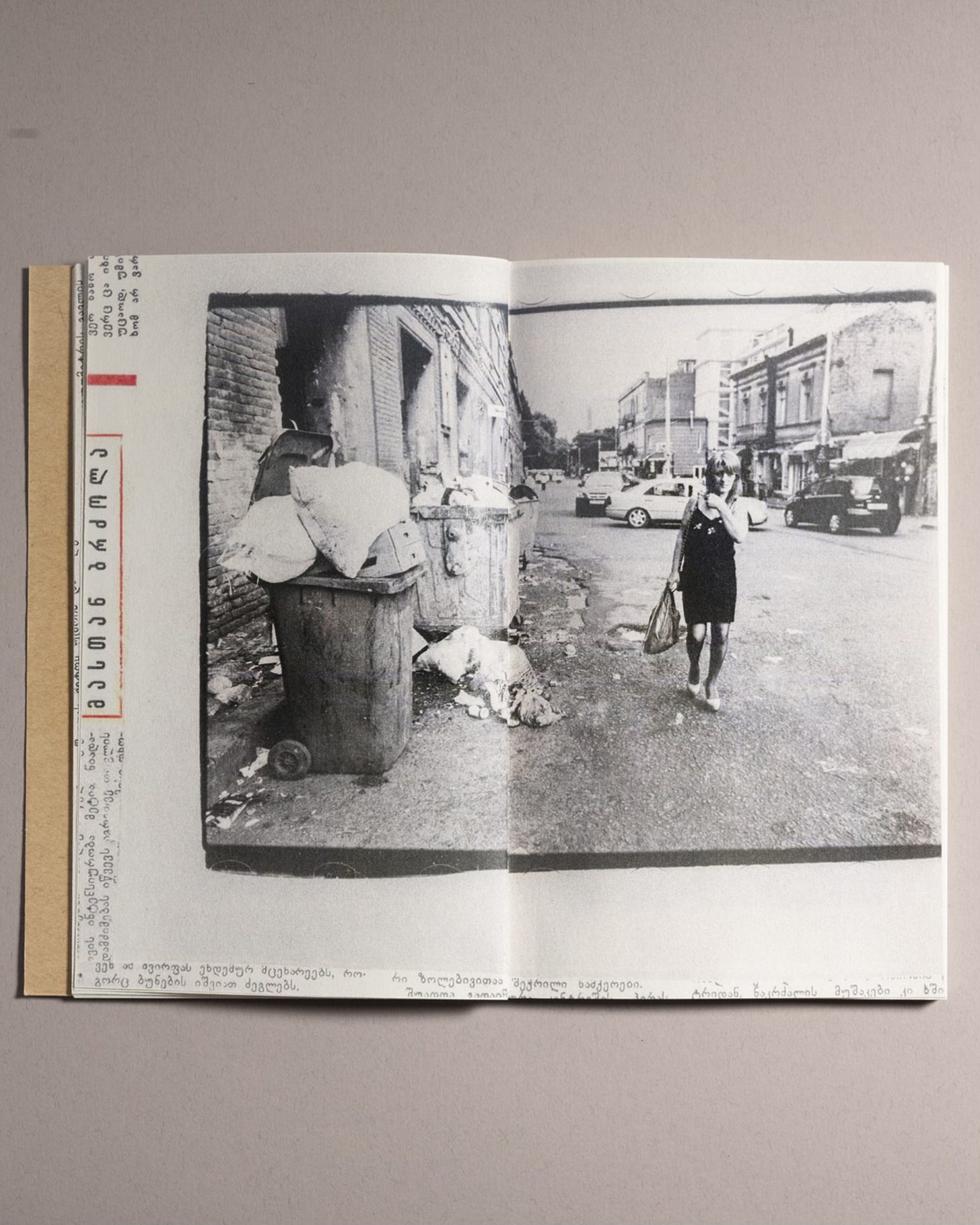

Film Director Gust Van den Berghe sees an uncertain presence in Bouts’ figures whereby ‘some of his characters do not grant us access to their feelings’. He likens this to unmoored meanings of actors faces in film rushes prior to fixing meaning in editing. Back at the Memling monograph, Hugo Pictor found mental images of 15th century altarpieces and portraits were turning into the photographic images of Station Square in Tbilisi, Giorgia, that appeared in Vakho Khetaguri’s The Fall (2024).

As the photographers’s short statement in this self-published book concludes: ‘This series I shot in 2013-2016 does not claim to fully represent reality. It is just an attempt to transfer the aura of this place on photographic paper.’ Another pocket-sized book.

Fearing an instance of Pictorian Over Hugo Association, Hugo Pictor tried to clarify the Memling-Khetaguri affinity. Both offered a world that showed off its ‘reality effect’, whilst highly stylised, by either paint or printing techniques. A ‘full’ world overrode a simple arrangement in perspectival space to create heightened surface patterns of emphasis and meaning that disrupted attention and picture planes.

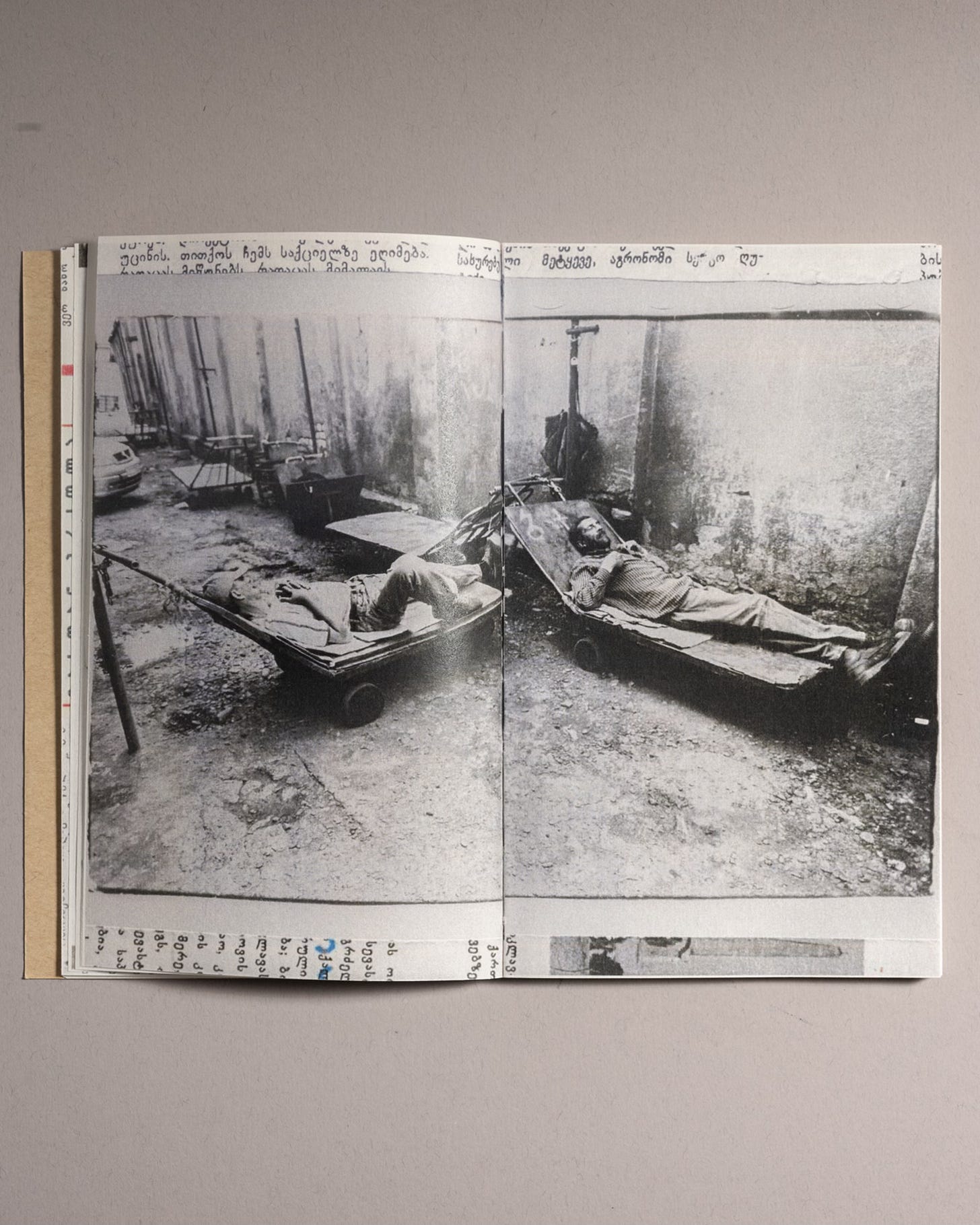

The progression through Khetaguri’s book was like reading across an altarpiece. Khetaguri, thought Hugo Pictor, found variants in Tbilisi for Memling’s use of the diptych, the architecture of rooms and thrones. As Memling’s detailing slowly revealed the Christian story - a veiled piece of cloth held by Baby Jesus is an intimation of his own burial shroud - so the photographs show a world in a long process of registering.

The Fall, for example, contains many images of people sleeping, or lying in the street, conditions where different states of time and being take moments to register and withhold. Even in images more akin to classic street photography, Khetaguri’s stylistic interventions create a delay, a lag in this process of registering akin to a long exposure time in early photography, the emergence in the dark room out of photographic paper.

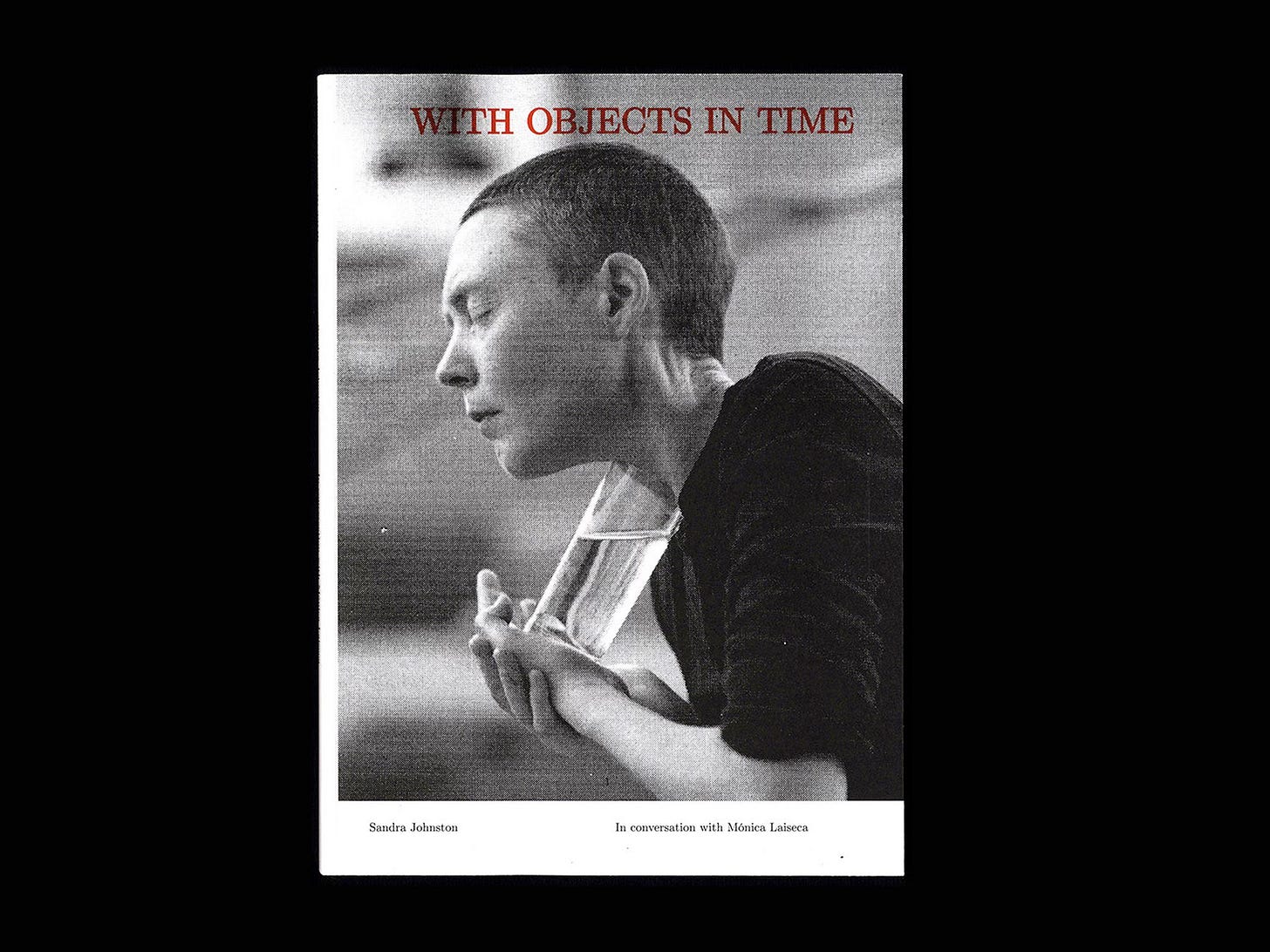

Hugo Pictor stopped, felt panicky, did again his physiological sigh breathing exercises. He would be pausing this newsletter soon, trying to discern what he was writing, thinking and why; how to gather, follow, collect, respond and discern. Was that best done by continuing on, pausing, or stopping? As he thought this, his eye encountered the cover of With Objects in Time, in which the performance artist Sandra Johnston had conversations about her work with Mónica Laiseca.

In that cover photo, the artist appeared to be leaning forward, eyes closed. In front of her chest she holds up both hands, palms open and on top of each other, to support the base of a tall glass of water, fixed/ balanced tightly, precariously against her neck.

How to read this concentration? Hugo Pictor saw the artist living-into a distinct moment of presence and relationships, akin to St.Veronica with her miraculous cloth in Memling’s Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi. This is also the artist figuring out how the performance should unfold. What follows? How to move on, beyond, and in?

With Objects in Time was a catalogue raisonné of sorts: stills from decades of performances, notebooks, locations, audiences. It let Hugo Pictor, who had not seen any of the performances, form a sense of the time, body, care, tension, presence, insistence, choreography of bodies and objects, that such performances involved.

Did the book have something of its own to contribute? It avoided a purely chronological view of an artist’s work. It was the motifs, themes, gestures, attentions, cares, objects themselves that unfolded, developed, and/or stopped. That image on the cover could be unfolding into another that was from 1980 or next week.

Hugo Pictor felt he had much to learn. A list of objects at the end of the book begins (‘in order of appearance’):

Dog bone

Drop of blood

T-shirt

Banana-coloured football boots

Fanta orange

Throw-away plastic rain poncho

Tables

Envelope

TightsOf those tights (her grandmother’s), Johnston writes:

An object can bring back the whole feeling of a person, their whole presence, and then it begins to relate to how you are in the world… There’s a reserve of emotion that’s just there and is played out endlessly through touch. The objects, they open like nerve points. And I feel that performance art - for me it’s not a conceptual exercise, I feel that I perform from the nervous system and when I’m improvising well it is because the whole body is listening.

Hugo Pictor was muttering as the Book Pile slid into the darkness, trying out words to see what fitted. Attentive he mumbled. Alert, attuned, present, lost, surprised, carrying, confounding, forgetting, complicating. Under his chin, the water rocked.