The Romford Oneiroscopist's Many Malls

Jan-Pieter ‘t Hart, Mateo Vega and Amsterdam's OUTLINE, Remedios Varo and Sussex Surrealists, Lucie McLaughlin's Vest Tops, Decisive Gestures, the exact location of Henry Fuseli's chips

The Amsterdam based artist collective Outline, defines itself as

a publishing platform and floating collective that aims to create interventions within intermediate spaces, and accelerate an exchange by connecting ideas, artefacts, individuals and localities.Hugo Pictor had a acquired two of their growing list of risograph printed publications, W-Street (plot points and non-fictions) by Jan-Pieter ‘t Hart, and We Do Not Yet Know What ‘Toto – Africa (playing in an empty mall)’ Can Do by Mateo Vega.

‘What I know, so far in the process, is this:’ begins W-Street: ‘our protagonist, A., will walk the entirety of one street.’ It is a straight road, but actually its name changes half way along, so ‘W-Street’ is a handy, simplifying fiction and ‘this void of abstractions and conjectures, this non-space of speculations’ leads our walker into thoughts of Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1985 short story She Unnames Them, in which Eve does just that.

Already by this second page the drift, mix and momentum is evident, embodied beautifully by the pamphlet’s design. The essay can be read straight through but the paper folds can be opened out to reveal more direct notations of this dérive, in words and also the traces, tracings, protozoic marks, dots and lines, of Tjobo Kho’s drawings (as seen first on the cover, above).

I will not trace the whole walk, but our narrator is an absorbing guide. The citations are sometimes from a canonical psychogeography bookshelf - Perec, De Certeau, Haraway - but that’s fine because ’t Hart meets and tests these words for himself, as reader, writer, walker, thinker. Text, drawings and design together are really a small case study of how to read, embody, constellate, mean, as George Perec identifies:

You’re no longer the inaccessibly, translucent, transparent one. You are afraid, you wait; on that crowded square you wait for the rain to stop falling.As befits a collective, Jan-Pieter ’t Hart writes the introduction for Mateo Vega’s We Do Not Yet Know What ‘Toto – Africa (playing in an empty mall)’ Can Do, framing what follows as an exploration of ‘the failed promises and lost futurity of consumer capitalism through their childhood and adult relationships to its architectural and sonic iconography.’

Vega’s biography leads him to compare the shopping centres of Lima in Peru and Amsterdam. His particular focus is the phenomenon of YouTube videos that alter the soundscape of pop songs to accentuate the aesthetics of music played through the sound system in an empty, closed mall. The popularity of these videos online, revealed in viewing figures and YouTube comments, evidence for Vega astonishing levels of affect, haunting, desire and nostalgia, to be both immersed in and critiquing.

What have we lost? What are we feeling? Is it politically significant that so many people feel this attraction to the ruins of Capitalism? Does it signal a desire for change, or just a fascinated, trance-like absorption in promise, ruin, failure alike?

The pamphlet concludes with stills of car parks, delivery lanes, illuminated loading bays, frosted windows, with the population down to a couple of ghostly children pushing a trolley past a Lidl sign. All monochrome, grainy, riso-tinted, scenes too familiar to figure as surreal and abstract but heading that way by working a strange vein of the too human inhuman non-human, film stills immersive but critical of this Beckett-like capitalist endgame under a pylon. ‘As much as I would like’ broods Vega, ‘I can’t pin down the sonic effect of the mall videos as purely radical or leftist.’

Hugo Pictor, meanwhile, was left with suddenly vivid sensations of his 1980s in Romford, Essex, that suburban hinterland’s remarkable layering of successive shopping malls that in his memory of it seem to burst up and decline and be replaced, in an unsettling, looping, simultaneity, accompanied by some very familiar echoing pop tunes.

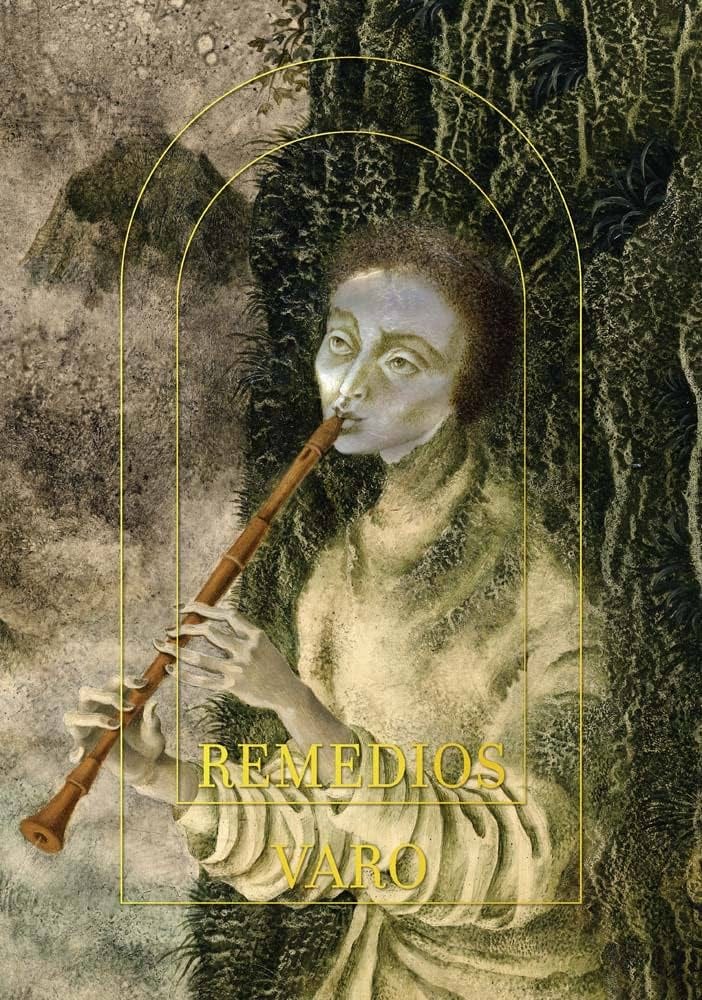

Greetings Remedios Varo! When the artist’s Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle (1961) and nun bicycling masterpiece To The Tower (1961) was all Hugo Pictor could think about after seeing Tate Modern’s 2022 Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition, he was alarmed to discover that the only books on the artist were being sold online by unscrupulous booksellers for £250. Now, thankfully, there is the catalogue for Remedios Varo: Science Fictions at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Hugo Pictor was so excited that he filled the time before it arrived in the post by dealing endless hands of Leonora Carrington’s Tarot card pack. There was Ithell Colquhoun’s tarot too, but Hugo Pictor wasn’t sure he was ready to experience the Occult as a set of vibrating cosmic colour fields.

From the Mexico of Varo and Carrington, Hugo Pictor’s mind drifted to the footsteps of Hastings Surrealism, in which he stepped every day. Eileen Agar and Edward Burra, in photography and watercolour respectively, had both recorded their time amongst the fishing boats on Hastings beach, whilst further along the promenade towards Bexhill Edith Rimmington had produced a peculiar set of photographs that haunted Hugo Pictor’s mind, although he could remember almost nothing about them but the faded colour scale of 1970s holiday photo albums (online searches led instead to yet another encounter with The Oneiroscopist).

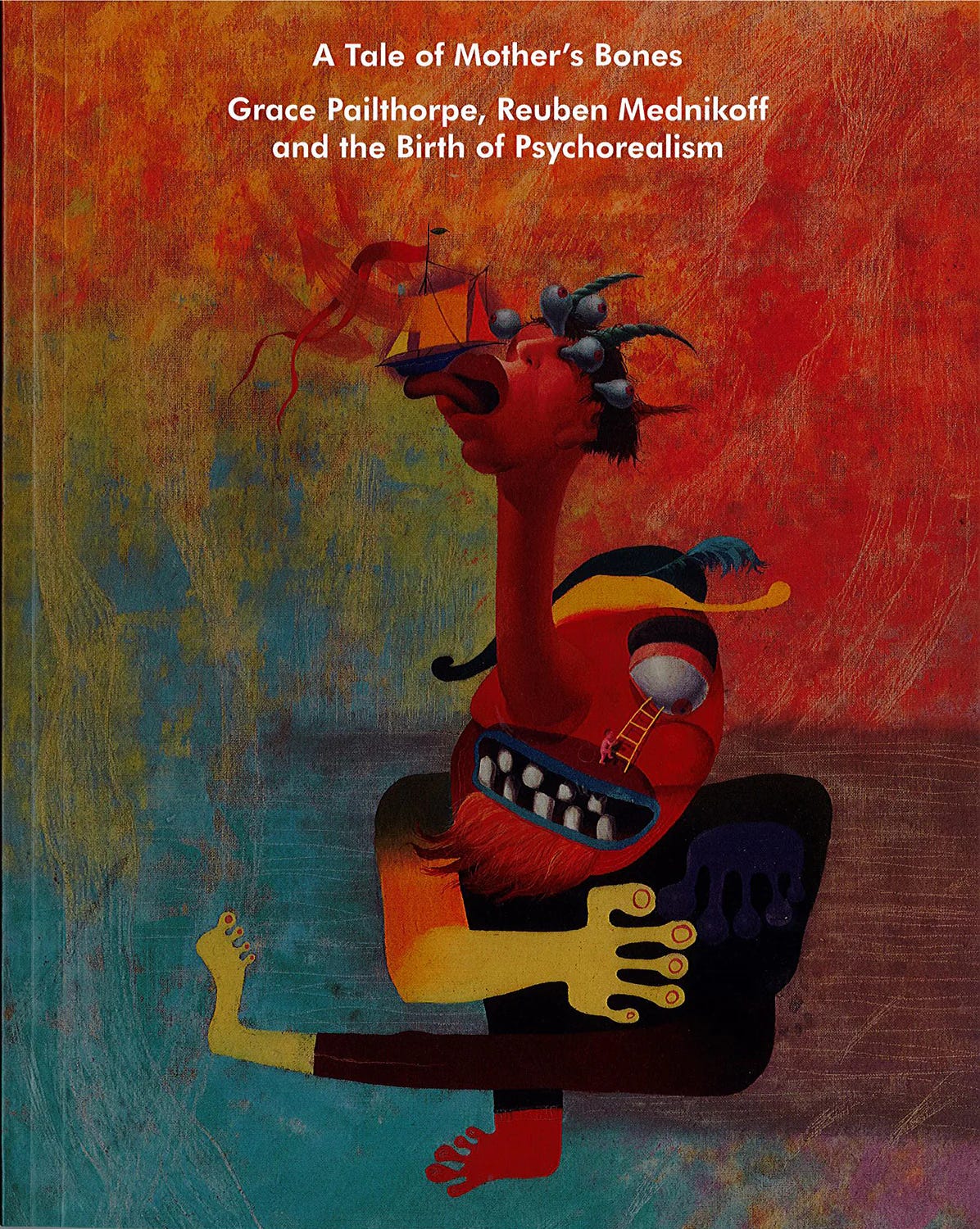

Above all, there was the antique shop of Ruben Mednikoff and Grace Pailthorpe in Battle, opposite the vets where Hugo Pictor had once taken his scottie-schnauzer cross when it was unbelievably itchy. Hugo Pictor couldn’t find the photo from that day on his phone so he went and celebrated the birthday of someone he did not know, stood in almost the same position amongst the fishing boats and sheds on Hastings beach as where Burra and Agar had painted and photographed.

Actually, Grace Pailthorpe’s Writings on Psychoanalysis and Surrealism, edited for Routledge by Alberto Stefana and Lee Ann Montanaro, is a rare collection of Battle-based Surrealist informed psychoanalytical writings with a connection to Hugo Pictor’s dog’s veterinary practice. Lectures on birth trauma, Surrealism, and Pailthorpe’s unfinished treatise on Psychorealism are the most substantial contributions, but shorter pieces analysing particular art works by one or other of this artistic couple, were a reminder of A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Rueben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism (and its accompanying publication).

Hugo Pictor remembered how the exhibition included several paintings hung in the air to show the written psychoanalytical interpretations attached to the back of the frame. The method reappears in the first article included in the Routledge collection, first published in The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis in 1938. A poem by Mednikoff (who is unnamed in the article) is subjected to six months of analysis, at the end of which the patient (Mednikoff) types it out again and observes:

While transcribing my poem I was interested to see how clear it was to me now. I found myself typing it with a running commentary going on in my head and seeing the whole scene of its origin.Sat in the shadow of a fishing boat, it was the confidence of Pailthorpe’s method that impressed Hugo Pictor, that any method could lead to the point where all this could go on lucidly and simultaneously. As Pailthorpe concludes her essay:

The peculiar interest of this poem lies in the fact that every single phrase had its unconscious reason. The unconscious inspired the poem. Not a single phrase or word was superfluous to the story it had to tell. Equally remarkable is the extraordinary way in which the unconscious selects from reality-experience the subject-equivalents to suit the unconscious needs. Its power of selection reaches an exactitude that is almost mathematic in its accuracy of sensation equivalents, for the unconscious situation is perfect in its association to the Karoo [the desert that titles the poem and which it describes at length].Back up on the West Hill of Hastings, a heavy thud signalled the arrival of Hugo Pictor’s Remedios Varo catalogue.

just begins, no title page or colophon, only the cover, before the text launches. A notebook? Gathering of fragments? Also a continuity, Vest Tops, Decisive Gestures by Lucie McLaughlin, with the direction and address of a letter: ‘deciding to write to you’. In which case, thought Hugo Pictor, the ample white space is not the gap between fragments and times but a part of the flow of thinking and writing and going on.

Descriptions of and reflections on writing by McLaughlin herself get spliced with snippets of favourite writers (Lispector, Cixous, Fanny Howe, Louise-Bennett…). These get presented with the same sense of the quotidian as an exhibition, watching used fleeces on eBay, or a romantic date’s celebrity family connections. Hugo Pictor remembered a Martin Buber essay in which he says that (as I remember it, where is that book?) approaching life with the pre-intention of writing about it is somehow damaging, spiritually suspect.

That is not the focus here. These 17 pages test another hypothesis, of accepting and living with that knowledge of writing in and amongst trips out with friends, swallowing, an Air BnB kitchen, Tuesday. A list of objects on the writer’s table that I want to read as focussing the auto-fiction strategies of Lerner, Ernaux, Heti, Kraus, with their shifting positions of Ben/ Sheila/Annie (author) to Ben/ Sheila/ Annie (character/ narrator), and here we have ‘Two overdue library books… A first aid training booklet’.

CUT TO: Laura Haynes introducing This is not a biography*: An anthology of Biographical Fictioning (The Yellow Paper Press, 2023), observing that Ernaux, Myles, Kraus, Levi, Bellamy, Glück and others:

demonstrate that the (auto)biographical is not absolute, that it is, by necessity, provisional, unanchored and contingent.‘Coaxed and goaded, we are biochemically deluded’ Haynes writes in the same essay. ‘Memory and interpretation bind with fact and reality.’ Add what seems to be McLaughlin’s particular take on the anxieties and tensions of writing like this:

I read novels that I dislike but can’t put down where the character’s ideal version of themselves is one in which they are intellectualised.Do we really live a life that can be contingent around Clarice Lispector quotes as much as trips to the shops? Hugo Pictor suspects he will always be working that out. Yes, with a jarring, an occasional lapse of faith (in Lispector? The shops?). Maybe the white space in Vest Tops, Decisive Gestures acknowledges this, enables the notations, thoughts, quotations to sit and balance, collect, doubt and affirm.

It is a control, too, of the self becoming chorus, and used fleeces. Write from the bottom as well as the top of the notebook page, McLaughlin tells herself. How to develop? The argument or thread we might expect in a pamphlet or essay gives itself over (up?) to the next instance of ‘ordinary affects’ (Kathleen Stewart’s phrase).

That could be in the room, the street, the page, just out of the pen, on the screen. One such feels like a conclusion, for now: the group of tourists in the street, the man pulling jasmine from a planter ‘rubbing it between his thumb and forefinger, before dropping it again.’ … What is the value of this? As Kate Briggs writes in her own contribution to This is not a biography*, there are situations when:

rhetorical decisions, stylistic decisions, genre decisions, emphatic-fiction-flagging or this-is-close-to-life framing decisions sound like responsibilities, which might be exactly what they are. Meanwhile, still thinking of his Surrealist ancestry, Hugo Pictor found himself coincidentally in the exact location of Henry Fuseli’s Ladies of Hastings (1798), with the addition of a bag of chips of sculptured Michelangelo-esque proportions.