Unable To Choose and Focus Precisely

Hanne Hagenaars & The Roundness of Loss, the Discipline Park of Toby Altman, Not about but is with Lorine Niedecker & Cid Corman

I’m not here because I’ve finished the book, grumbled Hugo Pictor. He had read 112 pages of The Roundness of Loss by Hanne Hagenaars when the Porlock interruption came. Was there anything that should be said at such an in-the-middle stage of engaging with a book? What would be the point? Surely, page 383 was beckoning.

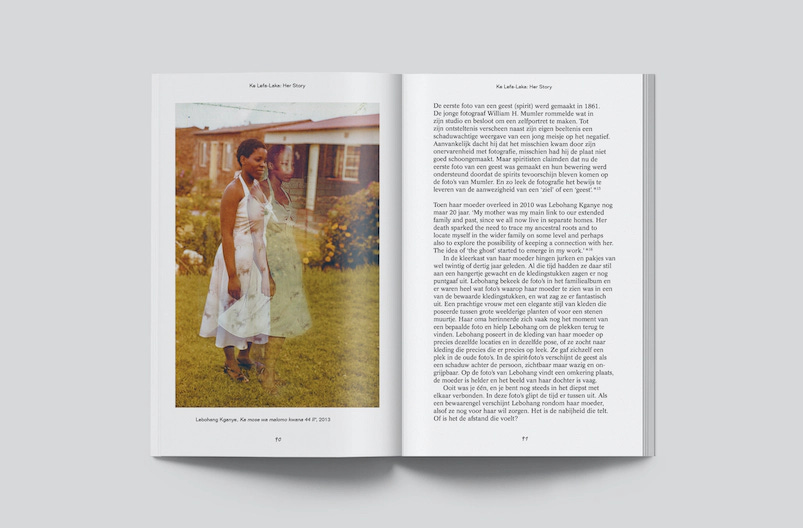

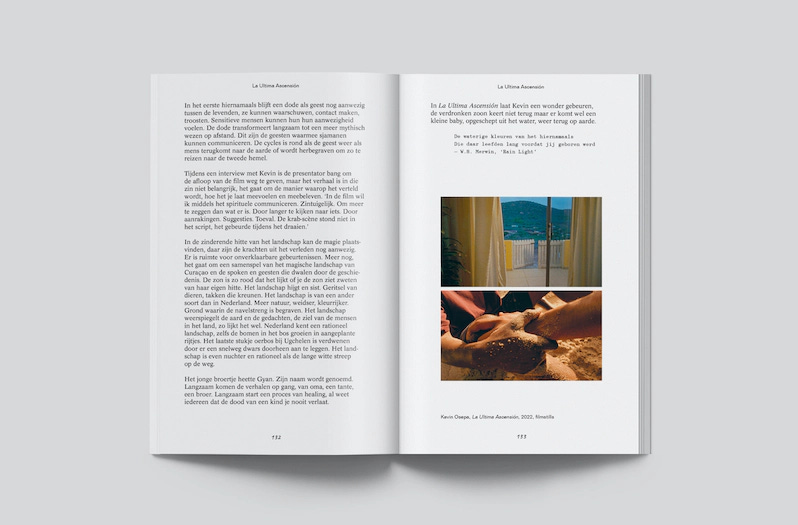

Hugo Pictor felt keen to record the encounter so far in 675 words, not quite sure where this assemblage of images and essays was going. It began with a short text - two thirds of a page - about the death of the author’s mother when she was 18, her quick disappearance from their lives, rarely talked about, no displayed photos in a house soon occupied by the father’s new wife. But, as the author writes: ‘There’s still time to make up for the deficiency of the silence. Here, a book for you.’

There follows several autobiographical chapters of family history, juxtaposed around full-page photographs of My Mothers Wardrobe, a 2022 photographic sequence by Hagenaars, in which (the artist’s?) hands hold, arrange and straighten what appears to be her mother’s clothing, although it has the size of six month old baby clothes.

As this ‘book for you’ unfolds, Hagenaars dreams of her mother during an ayervedic treatment in India, visits a healer in Amsterdam who has a conversation with mum’s soul, and recounts knowledge obtained from a shamanistic seance. In all three she is curious, open, and questioning. She finds an old photo of her parent’s wedding, in which her mum wears a snake skin bag that Hagenaars, not knowing its history, had once cut into strips for a school craft class. The Mexican artist Dodi Espinosa connects the skin to the mythical, cosmic snake that is a Mexican God.

A few pages later, as Hagenaars relates her own youth and early relationships, she turns to Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. These artistic connections are how Hagenaars will now proceed to explore grief, remembering and experience, through short essayistic encounters with different artists, in a book design that gives equal weight to this essaying and the full page reproduction of art works by Simone Hoàng, Marenne Welten, Lorena Torres and others.

Hagenaars writes proximal to encounters, with particular works and the artists themselves, in their homes and studios. Presumably some of these texts had origins in other reviews, catalogue essays and interviews but The Roundness of Loss never reads like a selected essays, but an emerging constellation of practices and relationships that forms and shifts within and between each accretional essay.

Artists Mariëlle Videler and Natalia Ossef, for example, both deal with grief and love - a cat, a partner, a people, a place, a history. Hagenaars immerses herself in each artist’s work, with the same intensity, sense of consequence and questioning as in the shamanic journey, the dream visions, the mum soul-summoning. At the same time, she seems to feel on surer existential ground with art works, their affect and materiality, their embodiments-of and urge to unfold.

Which means, thought Hugo Pictor, that p.113 is a place of questions. Will these accumulations of different artist’s continue? (He’d glimpsed some Alice Neel reproductions coming up). What will be the effect of that agglomeration? Already the book’s design was encouraging a palimpsest, where he could flick back, bring images and texts to permeate whatever page he was reading. And how will the author’s own autobiography figure, in its specificity and some vicarious (that didn’t seem the right word) enactment through the author’s curating of art works, artists, practices?

So far, if there was an single idea that stood out as a method for going forward, in the book itself and in Hugo Pictor’s next foray towards the book pile, it was something Hagenaars says of Nan Goldin:

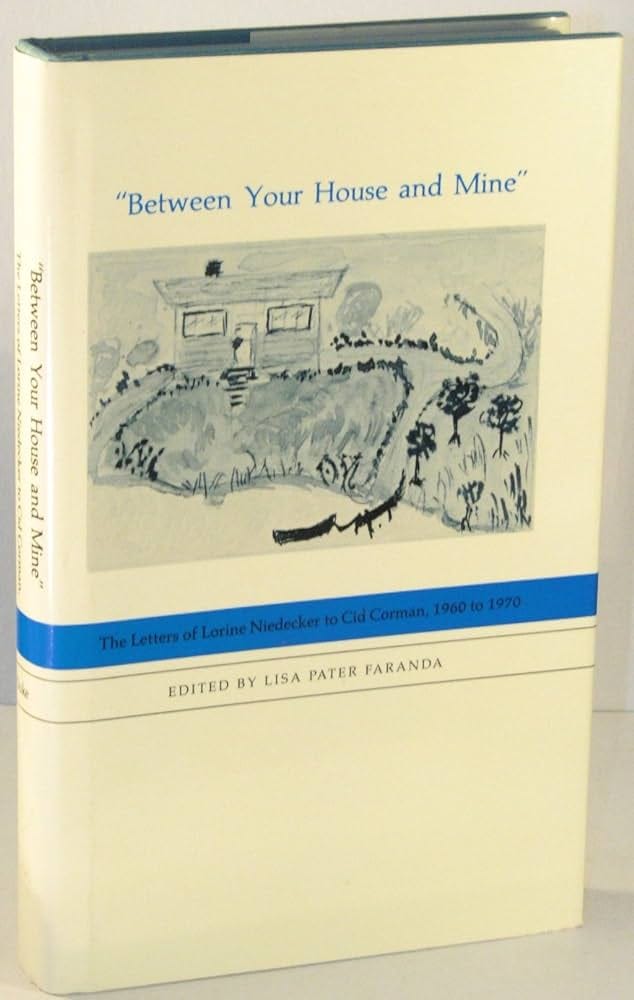

I have the impression that great photographers should also press the shutter with their eyes closed at the perfect moment, that photography is first and foremost intuition. Nan Goldin preferred not to wear glasses for her short-sighted eyes. Without those glasses she could not choose and focus precisely, but she had a a real gift foe the snapshot. And it prevented her as a photographer from selecting, from letting her norms define the photo. What is the real memory? Without selection. Without norms. To show it exactly as it was.Quickly, after last weeks Haiku experiences, Hugo Pictor’s journeys in the book pile took him from Harry Gilonis back to “Between Your House and Mine”: The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960-1970. In a letter Nidecker writes to Corman, Jan 10 1968, she compares a Bashō translation by Yuasa in her Penguin edition:

The changeable sky

of the northern districts

prevented me from seeing

the full moon of autumn.With Corman’s version of the same poem:

harvest moon

hokkoku weather

don’t depend on itWhat editorial principles might have guided Corman is summarised in his Introduction to One Man’s Moon: Poems by Bashō & Other Japanese Poets, where his texts are called ‘versions’ and Corman concludes:

It is rare enough - in any form - that anyone today finds poetry a way of ‘staying alive,’ yet that is what it is, if it has any validity at all.

And so it is they also still live with us. You can feel - if you let each syllable grow into - every moment of life comes to be shared - at depth.

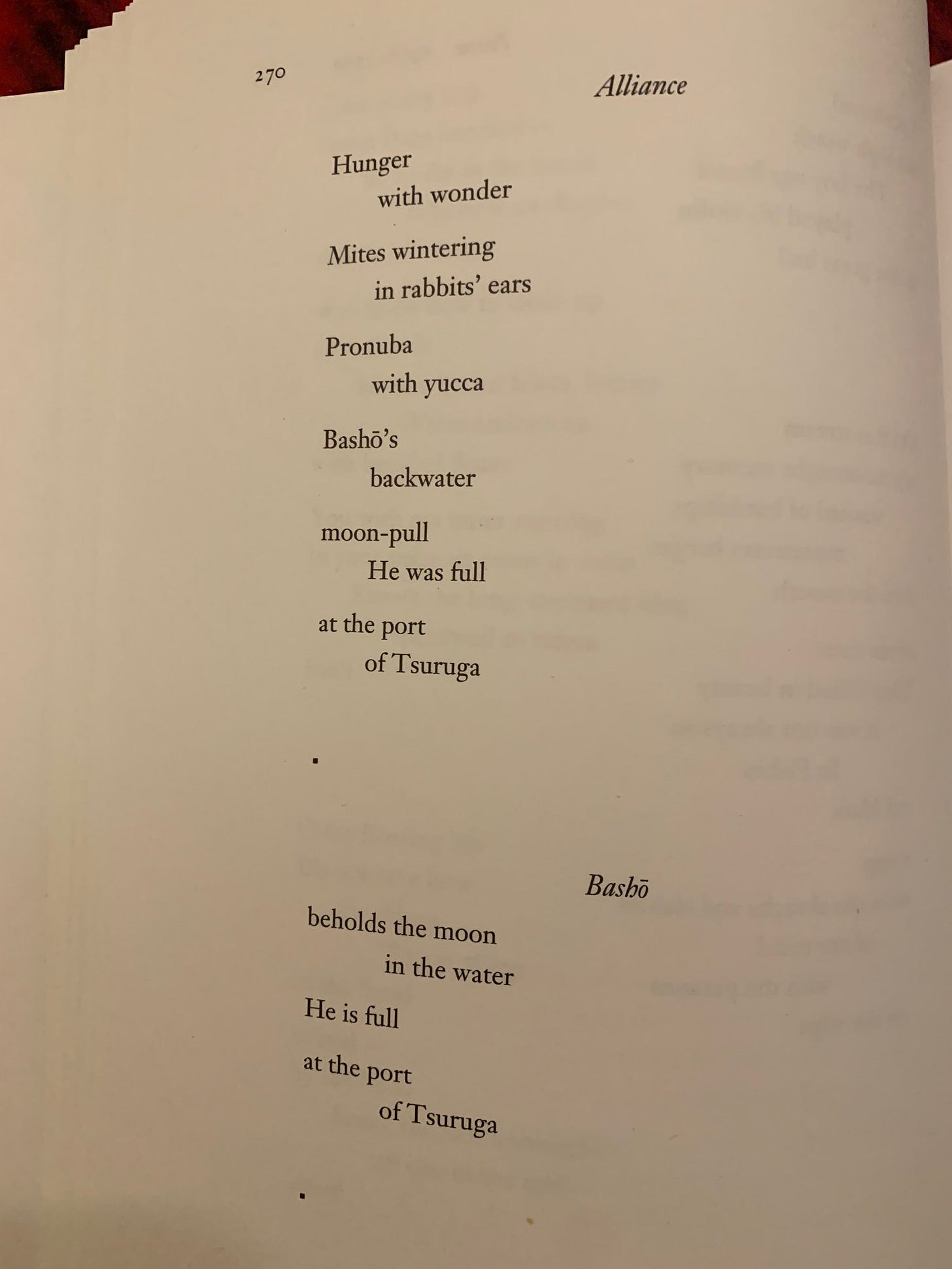

This is what it is - not about - but is.But is, mumbled Hugo Pictor to himself. But is. He was already following a faint memory back into the Lorine Niedecker: Collected Works edited by Jenny Penberthy. In two poems, likely written around 1968, Niedecker restlessly worked a small knot of Bashō. Full, port, moon, water, Tsuruga. The Bashō of “He was” and “He is” was/is where Hugo Pictor saw/ sees his own restless tenseness, and why/why the Wisconsin writer was/is likely his favourite poet of all of them:

Finally, but inevitably, Hugo Pictor was torn as always between wanting to write a coherent critical review, or dissolving into the webs/ morass/ [add your metaphor] of reading, thinking, worrying, being. Maybe that contradiction was powering Hugo Pictor towards… No idea. Then he began to write. Be quick, he decided, trying to capture that aftermath of reading Toby Altman’s Discipline Park from New York publisher and library Wendy’s Subway. Let it be… 680 words.

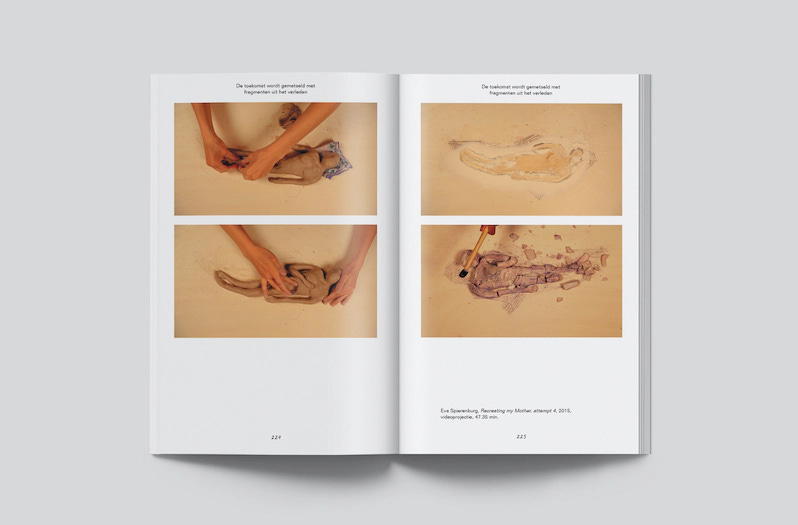

“I want to write an essay on scarcity” begins the book, although this paragraph is titled fig.1, which suggest it is a caption to the photo above: a black and white screen shot from an online time lapse film capturing the demolition of Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago in 2014, after it was denied preservation status as part of a proposed development by Northwestern University. The paragraph as a whole reads:

fig. 1. I want to write an essay on scarcity. To describe the city as an effect of deletion or decay: a shadow, a graveyard, a series of imaginary islands. I would begin, for instance, with the graves in Lincoln Park. I would say how the park was stripped of its corpses to make it clean and safe, a place where money stays. Or I would write about Daniel Burnham, who asked the city to build a harp of garbage in the lake. Who has time for that? I too live on trash. A woman’s face with an orange price tag on it. $7.99. A book of coupons. Wild onion collapsing in the throat. And what if the meek refuse to inherit?Altman’s book studies Brutalist Chicago architect Bertrand Goldberg, designer of many large, public housing and health facilities. To ‘study’ here means not only life and work, but the continued presence of his buildings (surviving and demolished), the attitudes and experiences people have with/in them, manifested in official documents, photos, memory, bodies, free association, conflicting emotions, disregard, &&&&.

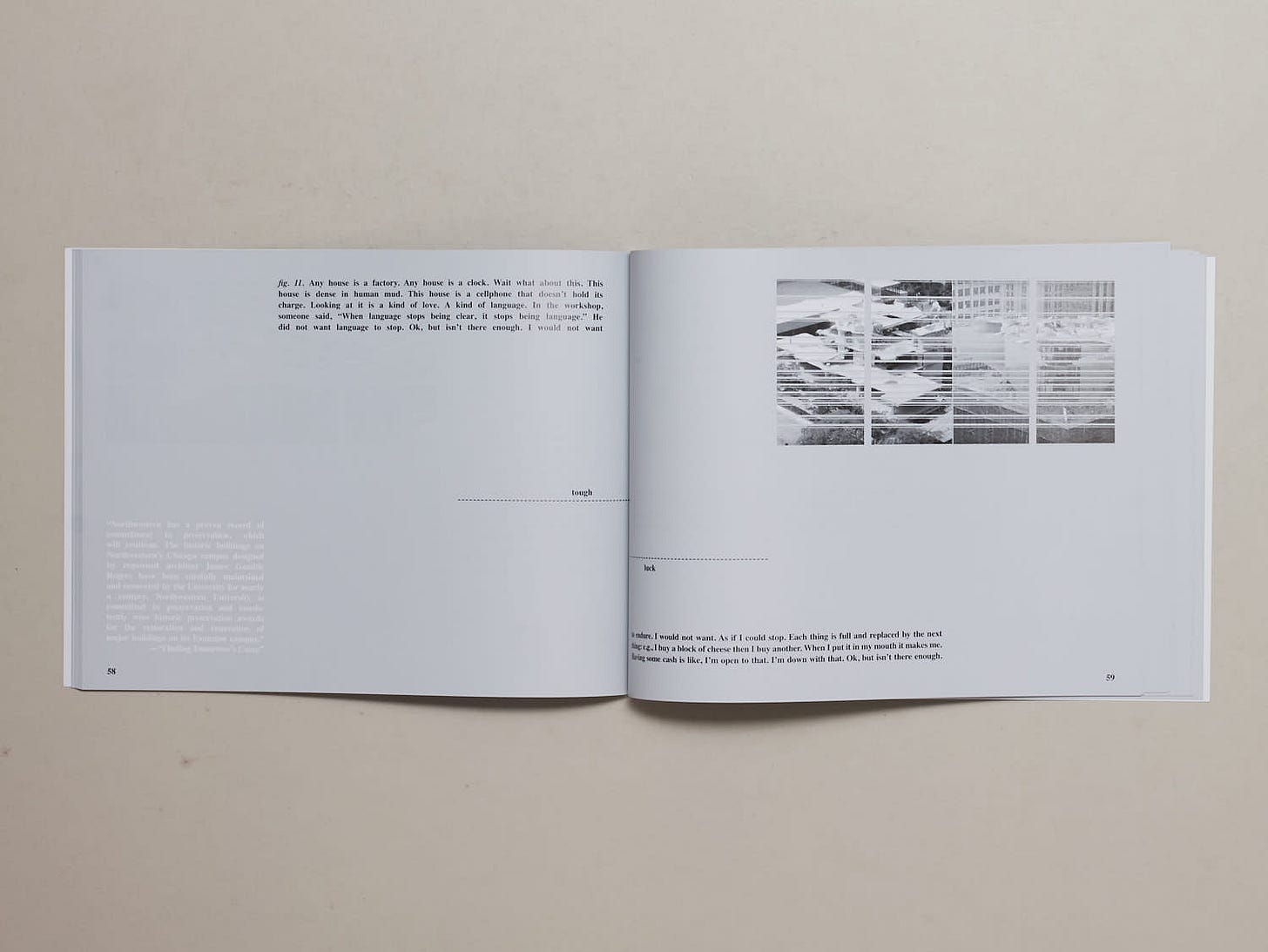

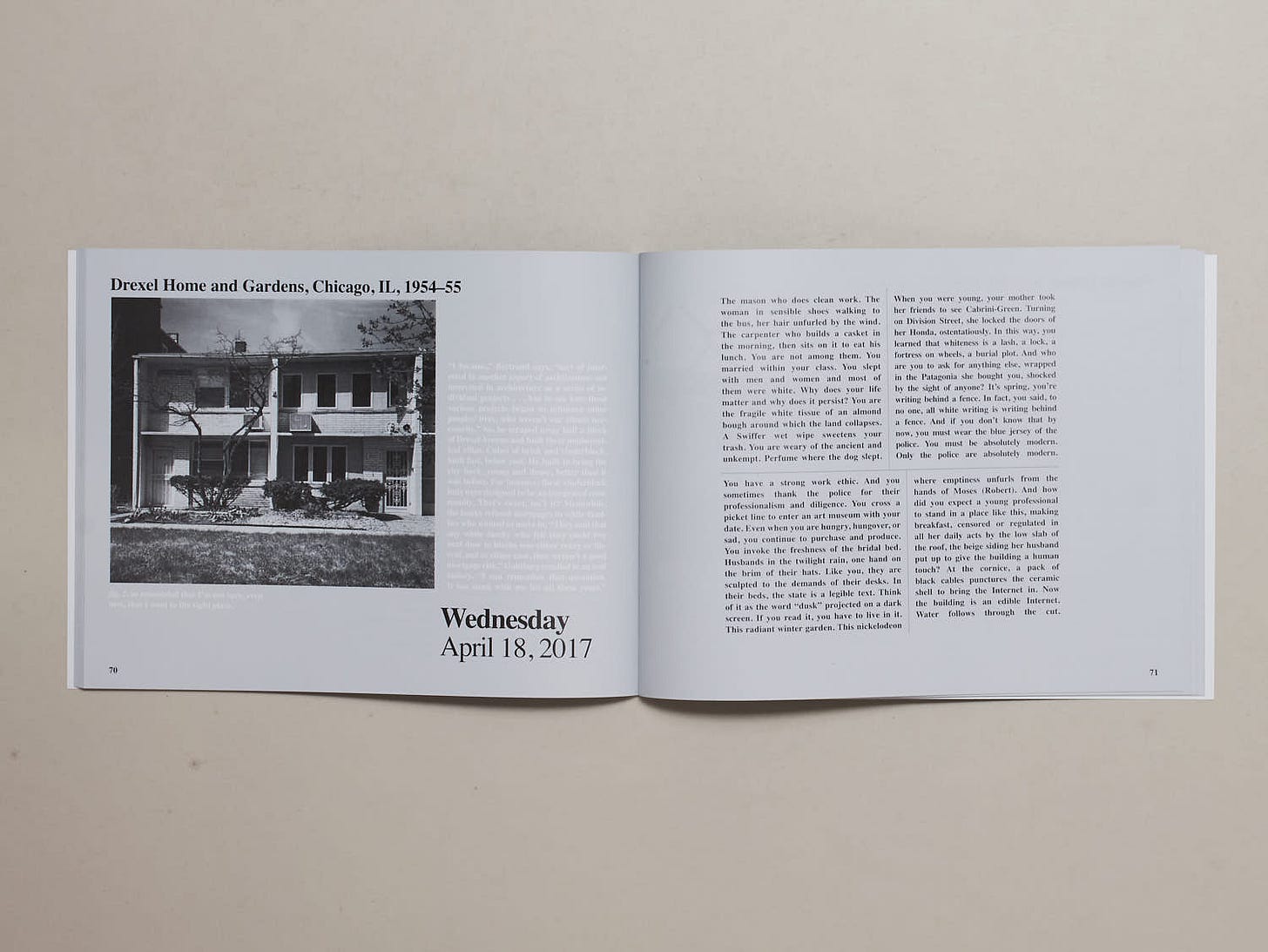

Altman’s ‘study’ has three sequences. Mandatory Fields (a memoir) and Bruise Smut are texts in constellation around images of the hospital demolition. The Institution and Its Moods is a survey of a number of Goldberg buildings which the author makes pilgrimages to, all around America, which offer the reader a series of case studies of the possible relations of writing, thinking, building, experience, and photography.

Essential to Discipline Park is the publication’s large landscape format, which adapts the design already implicit when sections appeared in magazines and chapbooks. Each page-spread (as the illustrations here show) is an assemblage of a photograph with often three different writings: blocks of text in black type and in grey scale, often (see above) with a minimalist notation that runs from recto to verso.

It all creates a dynamic sense of assemblage that derives its mix of functionality and experimental exuberance from Goldberg’s architecture. “Impossibly joyous” Altman calls these buildings. He wonders what prompted his obsessive exploration of them, noting both “something inexplicable” and that “this [Discipline Park] is not a book about political economy or institutional critique. No. This book is about love.”

Which means what exactly? shouted out Hugo Pictor. Altman: “If I knew the answers, I would surely tell you.” Now, in the after flush of reading, Hugo Pictor could only focus on individual paragraphs, like the one quoted above. Anything else he might think or write about Discipline Park seemed to depend on figuring what organised such modules, the spaces between one sentence and the next, how author and reader felt out the limits of what could be included, and how it could hold together, or not.

A momentary conclusion: how, then, did one look at such large imposing buildings, and write in a way that recognised them as institutional, fantastical, inside and outside, many geographies and temporalities, life giving and denying, emblematic and particular ( buildings that looked back). Hugo Pictor opened Discipline Park at random, found a paragraph written in response to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, built 1976-80 and visited by Altman on Monday, May 22 2017:

All forms of demolition are native to your mind. Last night, you lay on a yellow hill and the hospital was almost inside you, a cream beyond its lawns. Then you saw the bismol frothing at the root. All its acres are nauseous and untuned. You are its true landlord. Even in sleep the future pursues you.